Originally published 27 June 2004

Each of us is born at the center of the world.

For nine months our physical selves are assembled molecule by molecule, cell by cell, in the darkness of our mother’s womb. A single fertilized egg cell splits into two. Then four. Eight. Sixteen. Thirty-two. Ultimately, 50 trillion cells or so.

At first, our future self is a mere blob of protoplasm. But slowly the blob begins to differentiate under the direction of genes. A symmetry axis develops. A head, a tail, a spine. At this point, the embryo might be that of a human, or a chicken, or a marmoset. Limbs form. Digits, with tiny translucent nails. Eyes, with papery lids. Ears pressed like flowers against the head. Clearly now a human. A nose, nostrils. Downy hair. Genitals.

As the physical self develops, so too a mental self takes shape, not yet conscious, not yet self-aware, knitted together as webs of neurons in the brain, encapsulating in some respects the evolutionary history of our species, instincts impressed by the genes. The instinct to suck, for example. Already, in the womb, the fetus presses its tiny fist against its mouth in anticipation of the moment when the mouth will be offered the mother’s breast.

What, if anything, goes on in the mind of the developing fetus we may never know. But this much seems certain: To the extent that the emerging self has any awareness of its surroundings, its world is coterminous with itself. We are not born with knowledge of the antipodes, the rings of Saturn, or the far flung realm of the galaxies. We are born into a world that is scarcely older than ourselves and scarcely larger than ourselves.

And we are at its center.

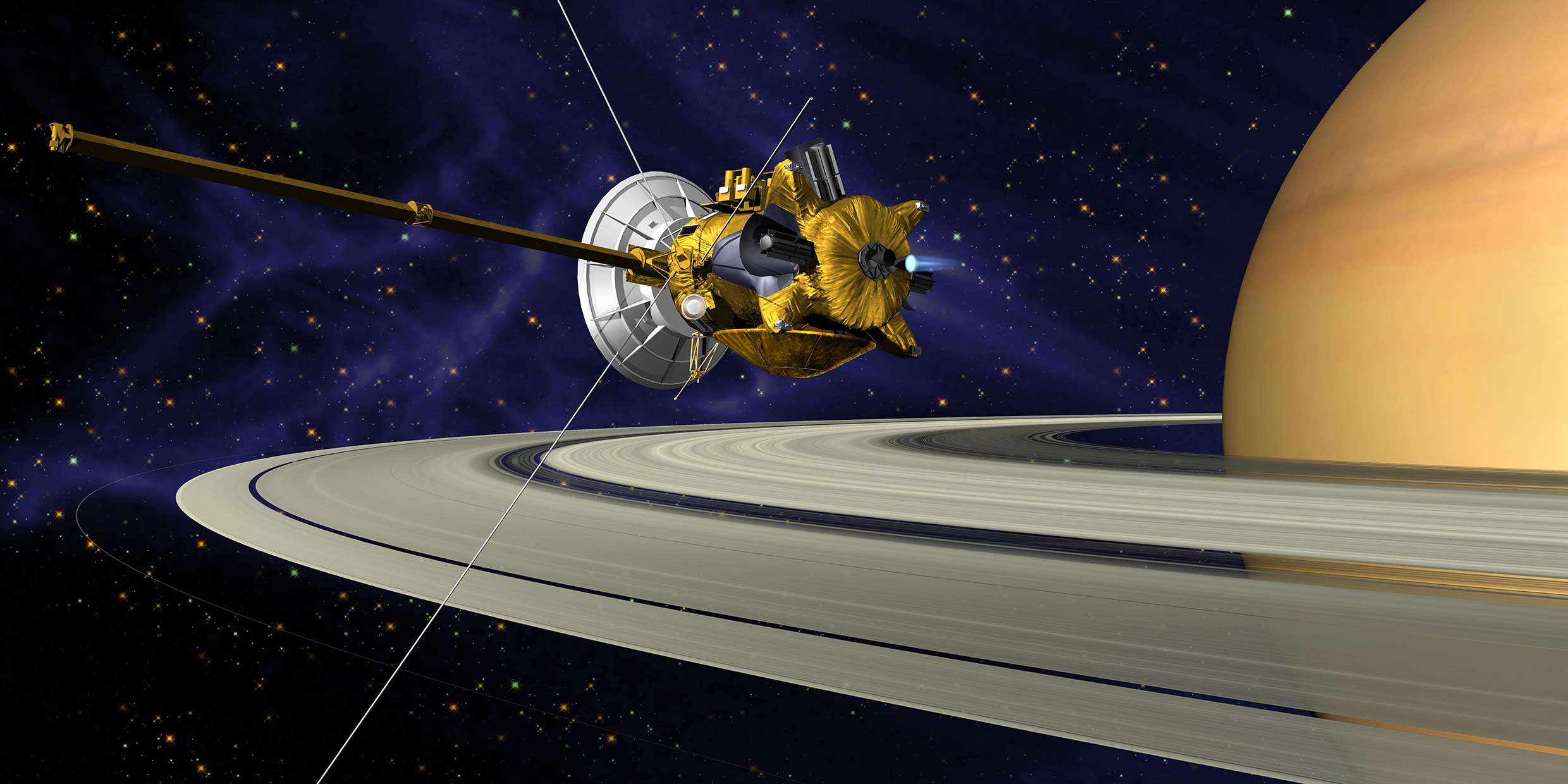

As I write, the Cassini spacecraft, named for the seventeenth-century astronomer who discovered a dark gap in Saturn’s rings, is closing in on the giant planet. If all goes well, it will be the first spacecraft to go into orbit around Saturn.

The craft will dash through the rings, drop a pod onto the surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, and spend four years studying the planet and its moons, continuing an investigation that began in the summer of 1610 when Galileo Galileo first spied Saturn’s rings through a telescope.

Galileo had no idea what he was looking at. We see what we expect to see, and who could have expected rings? He guessed that Saturn had two big moons, one to either side of the planet, moons that inexplicably soon disappeared.

During succeeding decades, other astronomers peered at Saturn through their instruments, trying to unravel the riddle. The Dutchman Christian Huygens was the first to guess the truth — thin, flat rings that are sometimes tilted to our view and sometimes seen (or not seen) edge-on. Nature has a way of confounding our expectations, turning out always to be bigger, older and odder than we have supposed.

The Cassini voyage to Saturn is a culmination of this extraordinary intellectual adventure, a thrusting of our species into greatness, into grandeur, away from the omphalos — world center — of our birth.

We are adept at finding ways to ignore the world as it presents itself to inquiring minds — the world of the light-years and the eons revealed by the scientific quest. The womb always beckons, with its comfort and security, its total enclosure by a loving, attentive parent. Perhaps we are genetically predisposed to favor ideas of the world in which we are central. We find a thousand reasons to affirm the cosmic importance of self, mistaking coincidence for causality, accident for necessity. None of us is immune to the siren call of the omphalos.

Another universe awaits us. A universe in which the whole of a human life is but a tick of the cosmic clock. A universe that may contain more galaxies than there are cells in the human body.

The journey into that universe requires courage — for each individual, and for our species. Uniquely of all animals, humans have the capacity to let our minds expand into the space and time of the galaxies. No other creatures can number the cells in their bodies, as we can, or count the stars. No other creatures can imagine the explosive birth of the universe 13 billion years ago from an infinitely hot, infinitely small seed of energy.

That we choose to make this journey — from the presumed center of the world into the vertiginous spaces and abyss of time — is the glory of our species and our most daunting challenge.