Originally published 11 October 1999

The World Wide Web is the first technological artifact that was not built from a blueprint.

Consider the most complex artifact you can think of: a supercomputer, the Space Shuttle, a high-energy particle accelerator, Boston’s new Central Artery. Somewhere in a bunch of file drawers is a set of plans that were in place before construction began. Even such simple artifacts as a stone chopper or copper bracelet are fashioned from a mental blueprint.

But the Web just grew like Topsy, willy-nilly, with astonishing speed. No one alive today understands it fully. Of course, the rules of the Web were designed from scratch, and the technology in which the Web resides was built to purpose, but the Web itself was created by millions of individuals worldwide, working in essential isolation from each other, and guided by a bewildering diversity of motivations.

The publicly accessible Web today consists of more than 800 million web pages, residing on several million servers and growing by a million pages a day. The great majority of these documents (more than 80 percent) contain commercial information, such as company home pages. Six percent are scientific and educational in content. Porn, government, and health related web sites account for one or two percent each. Personal websites add another few percent.

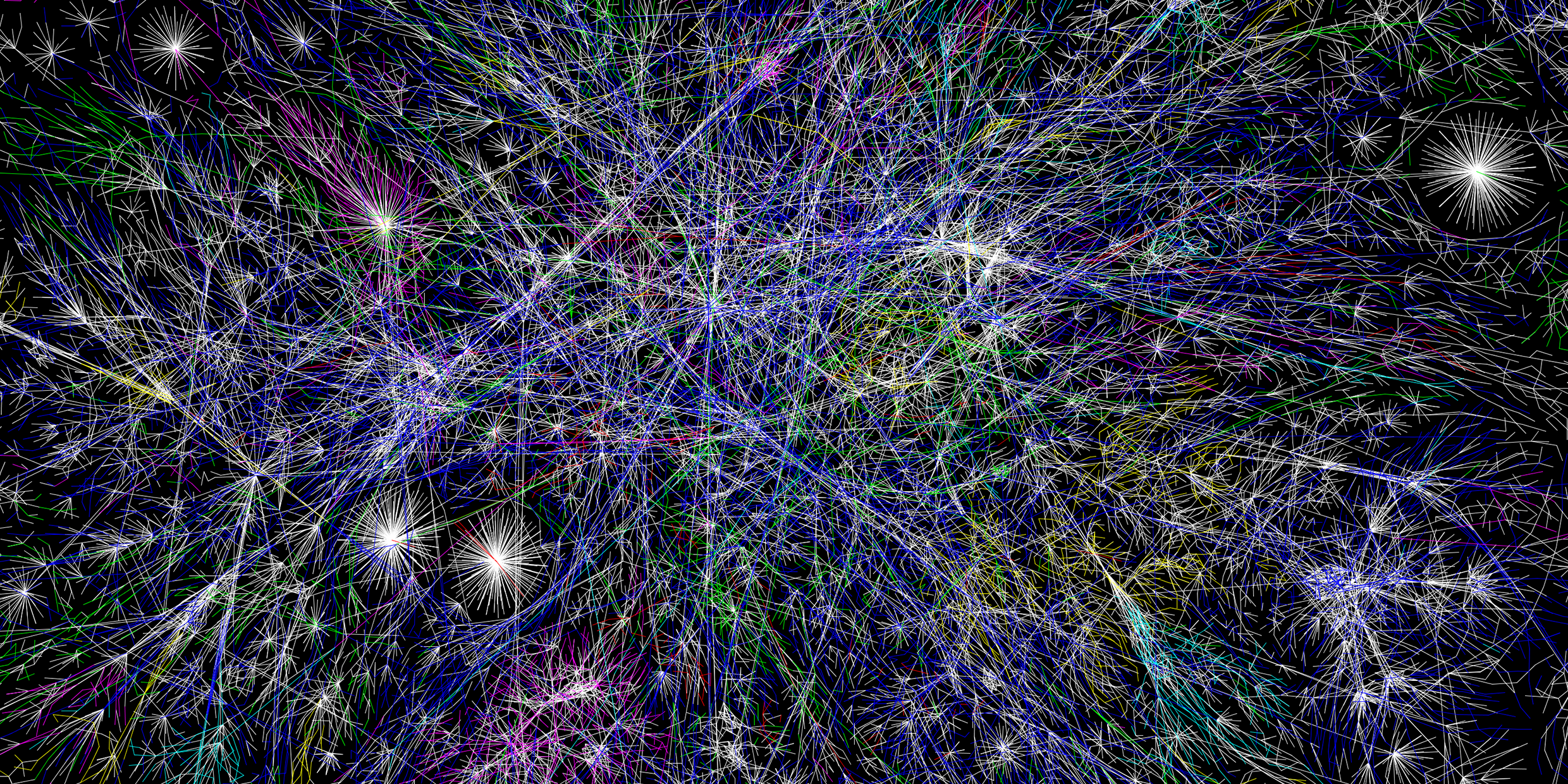

The documents are held together by billions of connections, called hyperlinks. These are the clickable words or phrases that let you jump from one page or site to another.

The Web resembles nothing so much as the human brain: hugely complex, mostly unmapped, an impenetrable tangle of nerves and connections.

Scientists have begun to study the Web as it if were a natural phenomenon, like the brain itself, trying to tease out patterns of order.

For example, three physicists at the University of Notre Dame asked themselves “What is the Web’s diameter?” They do not mean the spatial diameter, which is coincident with the surface area of the Earth, but rather the connectivity diameter: How many clicks does it take to get from any one place in the web to any other place?

They began by making a complete map of the nd.edu domain, the subset of the Web associated with their university. The domain contained (at the time of their study) 325,729 pages and 1,469,680 links. They found a mathematical formula for the smallest number of links that must be followed to find one’s way between any two pages in a web, as a function of the total number of pages. Their conclusion: no document on the present World Wide Web is more than 19 clicks away.

The formula is logarithmic. When the Web grows by 10 times, its “diameter” will only increase to 21.

This relatively small clickable diameter will be of interest to the people who provide us with tools for searching the Web. The Web’s vast wealth of information is useless unless we can find our way to it. So far there have been two main strategies for making it accessible.

Companies like Yahoo hire humans to surf the Web, evaluating content, and compiling hierarchical lists of sites that are likely to be of interest to their customers. These lists catalog only a small portion of the available sites.

The other strategy uses automated “search engines” to crawl the Web from link to link, indexing every word on every page. Type in a word or phrase, or a list of words or phrases, and the engine will return a ranked clickable list of every document that contains those words or phrases. The rank might depend upon such things as how many times the word appears on the pages, whether it appears in titles, how early in the text it appears, and so on.

Still, the “hits” returned by a search engine can be a dauntingly large collection of useful info and garbage. And even the best search engines, like Northern Lights and AltaVista, index less than half of the Web. Finding what one wants on the Web becomes increasingly difficult at the Web grows bigger.

A kind of “arms race” exists between designers of search engines and the webmasters who want to attract you to their pages. A commercial site, for example, might put on its home page every conceivable word or phrase that a potential customer might look for, repeating key words many times, in a type that is the same color as the background. The words are invisible to the page viewer, but “visible” to the search engine. The intent is to force the site to the top of ranked lists.

The next generation of search engines will look at incoming and outgoing hyperlinks as a measure of a page’s importance. Webmasters will certainly subvert this strategy too, by including superfluous links. Popular pages will get more popular, and new pages will have an increasingly difficult time making it onto search engine listings.

Competing forces such as these will drive the Web into undreamed-of patterns of connectivity — a kind of unplanned evolution by natural selection. Scientists who study the Web will be hard pressed to keep up.