Originally published 19 March 1990

The poet Muriel Rukeyser wrote, “The universe is made of stories, not of atoms.”

This thought is quoted approvingly by Bruce Gregory, Associate Director of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, in his delightful book Inventing Reality. Physicists do not discover the physical world, says Gregory. They invent a physical world. They make up stories that fit as closely as possible the facts created by their experimental apparatus.

I suspect that most physicists and philosophers of science would agree with Gregory — and with Rukeyser. The universe is made of stories. Even atoms are a story. The challenge is to know when a story is true.

Consider the following story, which is usually called “The Big Bang.”

The universe began 15 billion years ago in a singular explosion from a state of infinite energy density. As the primeval fireball expanded — everywhere — pure radiant energy condensed into material particles, particles formed atoms, atoms formed stars and galaxies. The outrush continues today.

It is a spectacular story, a modern creation myth, the new Genesis. But is it true?

Thirty years ago [in the 1960s], the answer was “maybe.” In those days, two creation stories contended for our attention, “The Big Bang” and “The Steady State.” Both stories had their beginning in Edwin Hubble’s discovery in the late 1920s that the galaxies are moving away from one another.

The observed facts were these: When light from a distant galaxy is passed through a prism and captured on a photographic plate, the pattern of colors (the particular wavelengths of light emitted by atoms) is shifted toward the red end of the spectrum. The more distant the galaxy, the greater the shift.

If the galaxies are rushing apart, their light would be stretched and reddened in exactly the way we observe. No one could think of any other way to explain the observed facts. Hubble’s conclusion: The universe is expanding. Space is getting bigger like the surface of an inflating balloon, and the galaxies are carried apart like dots on the balloon’s surface.

The Big Bang story was one way of explaining the expansion: “The universe began in a cataclysmic explosion and is still rushing outward.”

The Steady State story was an alternative explanation:

The universe has always looked more or less the way it looks today. As galaxies move apart, new matter is created in the intervening void. This new matter forms new galaxies, thus insuring that the average density of the universe stays pretty much the same. The universe had no beginning and will have no end.

But which story is true? Thirty years ago, teachers presented both stories to students and said “take your pick.” The choice was a matter of personal preference, one’s affection or distaste for beginnings.

But perhaps there was an observational way to decide between the two stories. Physicist Robert Dicke of Princeton University had predicted that if the universe began in a super-dense explosion, the afterglow of the Big Bang should still fill the universe, although the light would now be much cooled and weakened by expansion. He also predicted exactly the spectral distribution that this primeval light should have — exactly how much energy at each frequency in the spectrum.

Then, in 1965, two engineers at Bell Telephone Labs in New Jersey, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, were testing a big new microwave antenna. They had a problem with noise that just wouldn’t go away. The noise did not seem to come from the Earth, nor even from the Milky Way Galaxy. No matter what direction they pointed the antenna the noise was the same.

Although Penzias and Wilson had never heard of Dicke’s prediction, it turned out that the “noise” in their antenna had exactly the characteristics of the flash of the Big Bang. Suddenly, one story started looking much better than the other.

Other measurements of this cosmic noise were soon made at other frequencies, and the details of Dicke’s prediction was further confirmed. But these efforts were hampered by the fact that for much of the spectrum, radiation from the Earth’s atmosphere obscured and overwhelmed the signal from space.

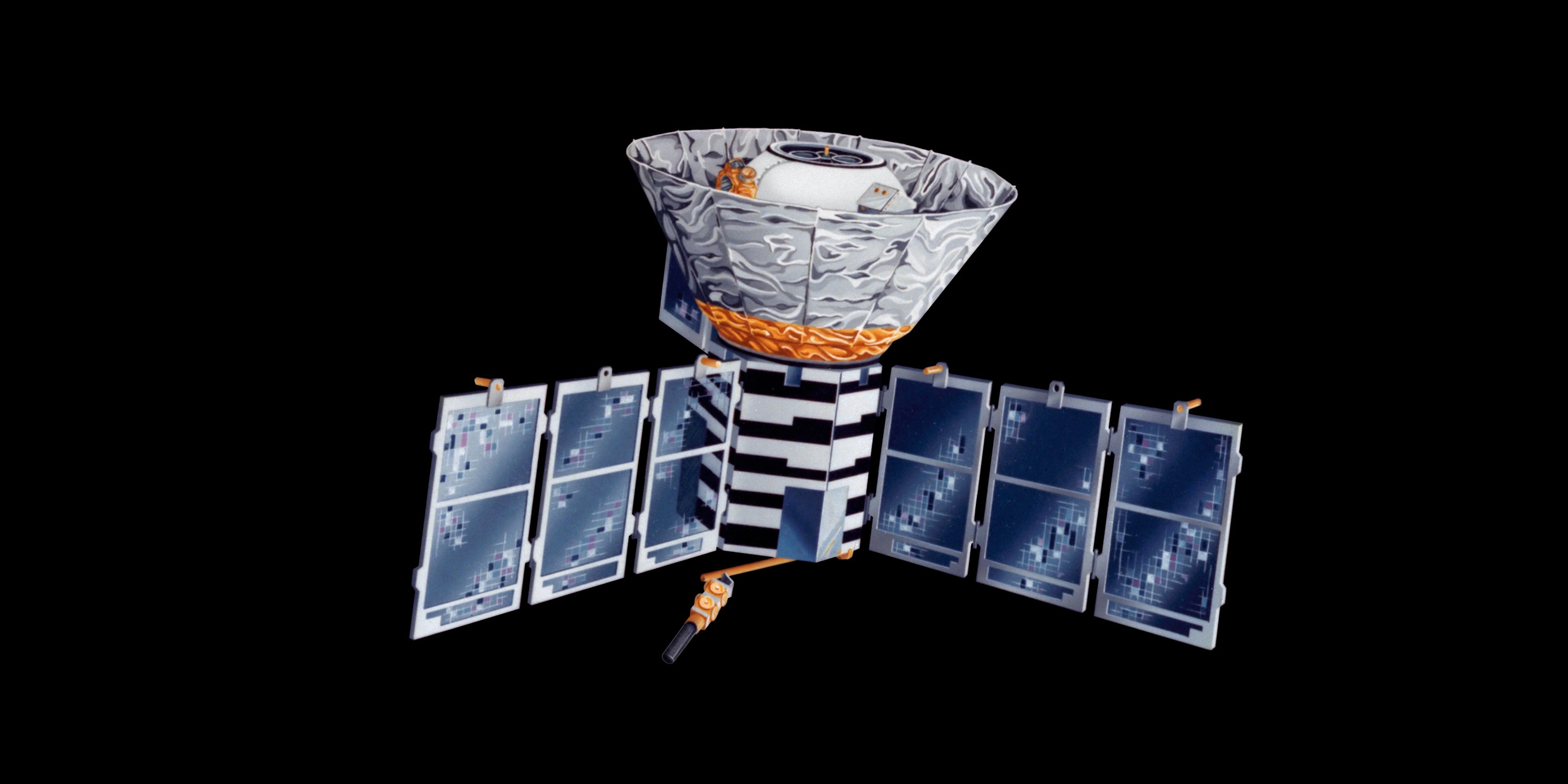

On November 18, 1989, NASA launched into space a satellite especially designed to look for the afterglow of the Big Bang, the Cosmic Background Explorer, or COBE. The detectors in the satellite would not be hampered by the Earth’s atmosphere.

In January [1990], preliminary results were announced at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society. John Mather of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center flashed a slide on the screen before the assembled scientists. It was a plot of the background radiation measured by COBE across the entire spectrum of frequencies. The fit of the data points to the predicted curve for the Big Bang’s afterglow was like beads on the string of a necklace.

The audience broke into spontaneous applause.

“Real” is an honorific term we bestow on our most cherished beliefs, says astrophysicist Bruce Gregory. The spontaneous applause of the American Astronomical Society for the COBE data plot was a way of bestowing honor on one story, the story called The Big Bang.

The story of our beginning.

John Mather and COBE science team colleague George Smoot were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2006 for their work confirming the story of the Big Bang. ‑Ed.