Originally published 25 February 1991

One could say of the Big Bang what Mark Twain said of himself: Reports of its death are greatly exaggerated.

Recent stories in the news media have suggested that the Big Bang theory is in trouble. New observations of distant galaxies and quasars are not consistent with the idea that the universe began 15 billion years ago in an all-embracing explosion — or so these stories seem to imply.

Don’t believe it. The Big Bang is alive and well. Nevertheless, some physicists have felt the need to come to its defense. The University of Chicago’s David Schramm, in particular, has tried to correct public impressions that the theory has been proven wrong, with interviews and letters to the popular press.

It is true that observational astronomers have presented Big Bang theorists with some thorny problems, but they have more to do with how the universe evolved once it got started than with the Big Bang itself. Apparently, galaxies are clumped together on a larger scale than the standard Big Bang theory can readily explain. And galaxies seem to have formed earlier in the history of the universe than the theory predicts.

Evidence still persuasive

In spite of these difficulties, the evidence for an explosive beginning for the universe 15 billion years ago remains as convincing as ever. “Just because we can’t predict tornadoes and earthquakes doesn’t mean we throw out the round Earth theory,” says Schramm. And most cosmologists would seem to agree: the Big Bang remains a firm part of our knowledge of the world.

It wasn’t always so. Seventy years ago, astronomers furiously resisted the idea that the universe had a beginning in time, or that it began with a bang. They favored the idea that the universe had always existed more or less as it does today — the so-called Steady State theory.

Then, in the late 1920s, Edwin Hubble and Milton Humason discovered that the galaxies are racing away from one another. If the galaxies are moving apart, then they must have been closer together at some time in the past. A simple calculation showed that 15 billion years ago all the matter and energy of the universe was contained within a seed of infinite density. The Big Bang theory was born.

Still, astronomers resisted. Few scientists liked the idea of a beginning. Even fewer liked the idea of a violent beginning. Theoreticians struggled to explain the outward flight of the galaxies without invoking a special moment of creation.

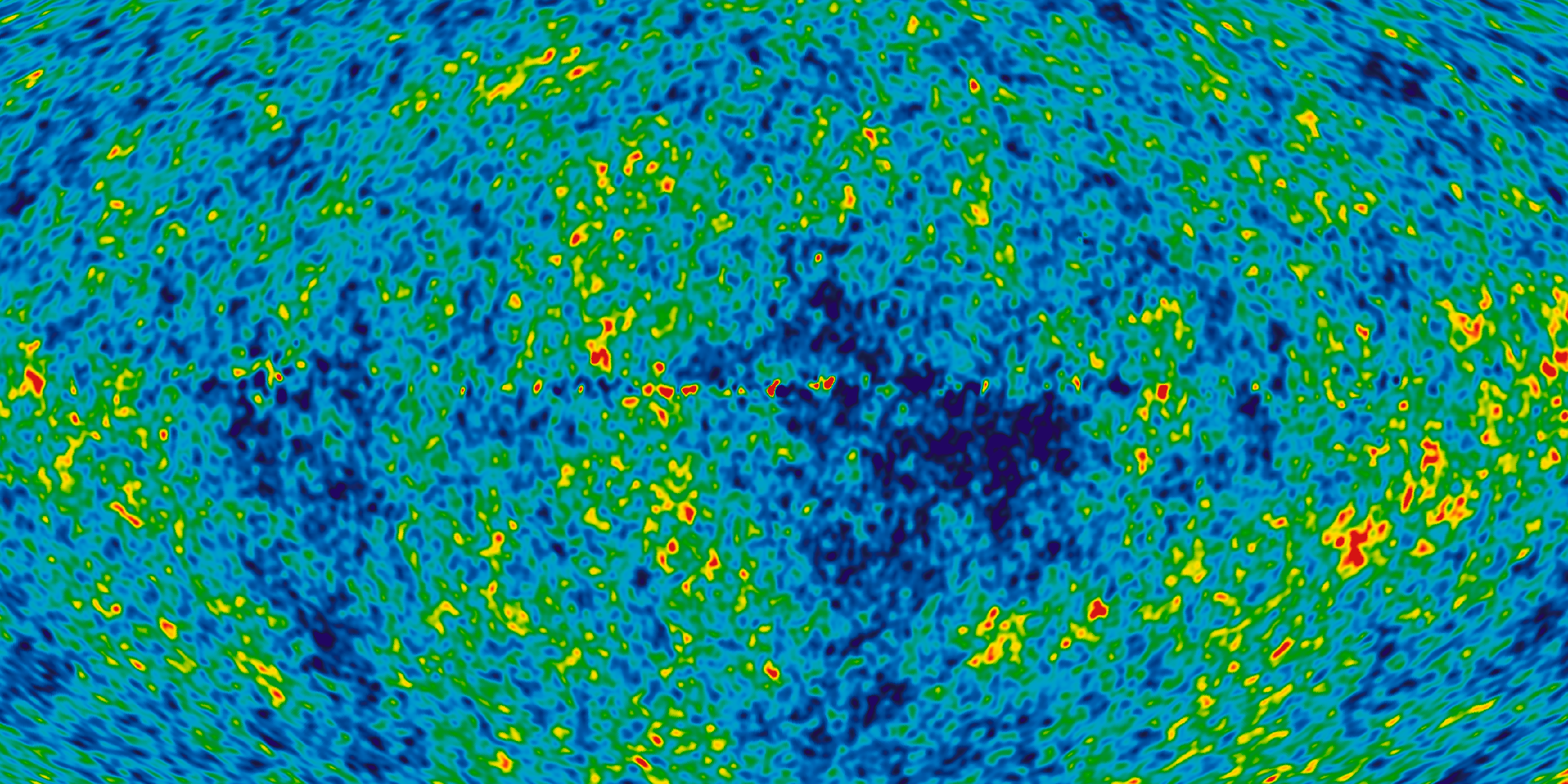

Then, in the 1960s, astronomers observed the flash of the Big Bang, now much diluted by expansion, an invisible microwave energy that uniformly fills the entire universe, with precisely the spectrum of frequencies predicted by the theory. Suddenly, the Big Bang theory acquired a compelling argument in its favor and most scientists jumped on the bandwagon.

Just last year, the flash of the Big Bang was observed again with unprecedented precision by the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) satellite. The spectrum of the flash and the uniformity of its distribution throughout the universe agree with predictions of the Big Bang theory to at least one part in a hundred thousand. When a graph of the COBE data was projected onto a screen at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society the audience broke into spontaneous applause — for the Big Bang.

So, for the time being, the Big Bang is safe. Scientists have not only learned to live with an explosive beginning for the universe, they have even become attached to the idea. But if some new evidence comes along that throws the Big Bang into disrepute, then they will learn to live with that too.

Certainly scientists will fight hard for a favorite idea, and they are pleased when their theories stand up to the test of experience, but they don’t sit around wringing their hands when a theory is found wanting. A mismatch between theory and experiment means exciting new problems to be solved, and, eventually, a better theory. The name of the game is not truth, but the search for truth.

A capacity for change

Science may be unique among belief systems in that it prides itself in its tentativeness. In his book Perfect Symmetry: The Search for the Beginning of Time, physicist Heinz Pagels says, “The capacity to tolerate complexity and contradiction, not the need for simplicity and certainty, is the attribute of an explorer.”

Pagels reminds us that modern science was born centuries ago when some people suspended their search for absolute truth and began instead to ask how things work. Only by being open to change, even radical change, are we able to make progress in the search for truth, says Pagels.

So let the troubling observations roll. We may not know the final truth about the origin and evolution of the universe, but we certainly know more today than at any time in the past, and in the future we will know even more. It is science’s vulnerability to change that is the source of its strength.