Originally published 15 November 1999

A shiver went up our spines when we read about the recent discoveries at Moula-Guercy cave in France. Archeologists found a treasure trove of 100,000-year-old bones of Neanderthals — our nearest cousins on the human family tree — along with the bones of deer and other animals. The evidence of the bones seems unmistakable: the Neanderthals who inhabited Moula-Guercy cave were cannibals.

The slash marks of stone tools on the bones clearly show that two young Neanderthals had been carefully filleted. Muscles were sliced from their heads, and the tongue cut out of at least one. The leg bone of an adult had been smashed open for the marrow. The butchered carcasses of Neanderthals and deer were tossed in a pit.

“Human and mammal remains were treated very similarly,” said one of the excavators, Alban Defleur of the Université de la Méditerranée at Marseilles. “We can safely infer that both species were exploited for a culinary goal.”

Fifty years ago this grim news would hardly have raised an eyebrow. Back then, Neanderthals were considered brutish subhumans blessedly made extinct about 40,000 years ago by the rise of anatomically modern humans. In his widely-read book, The Outline of History, published in 1920, H. G. Wells called Neanderthals “the grisly folk.”

In Wells’ view of history, which was then shared by many scientists, the triumph of modern humans over Neanderthals was the triumph of reason, imagination, and a lofty moral vision over ugliness, barbarity, and amorality.

Then along came the novelist William Golding, best known as author of Lord of the Flies. His 1955 novel The Inheritors turned the story on its head. Golding’s Neanderthals live in a state of childlike innocence, possessed of wonder and imagination. They do not willfully kill other animals. They are sexually restrained, and charmingly uninhibited in their nakedness.

Into their Eden-like existence come the violent, licentious, and cannibalistic Cro-Magnons — our immediate ancestors. The gentle Neanderthals are no match for the crafty and cruel new arrivals. The Neanderthals perish and Cro-Magnons inherit the Earth.

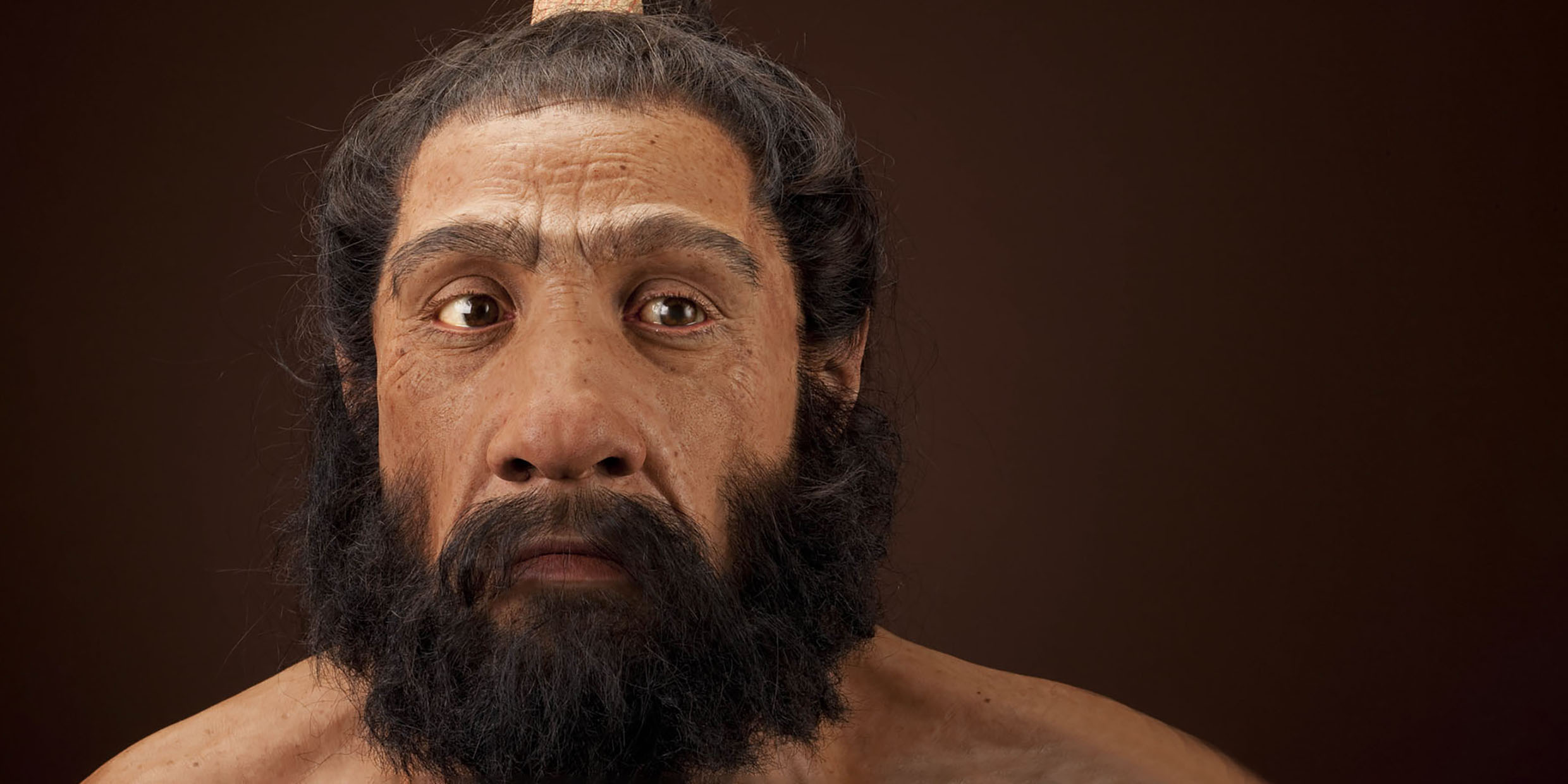

Golding’s reappraisal of Neanderthals had its parallel in science. Anthropologists found reasons to believe that Neanderthals made tools, clothing, and shelter, used fire, decorated their bodies with ornaments, and occasionally buried their dead. There is circumstantial evidence that they cared for the aged and handicapped.

It is our own Cro-Magnon ancestors who are now cast as the “grisly folk,” bent on exterminating their peaceable, less technologically advanced rivals. This revisionist anthropology was part of a post-60s examination of conscience that led us to question all forms of cultural and species imperialism. Neanderthals rose in our estimation, from subhumans deserving of their harsh fate to innocent victims. That’s why we felt a shiver of revulsion when we heard about Moula-Guercy. We like our heroes pure.

But idealizing Neanderthals is as foolish as demonizing them. The chopped and scraped bones from the French cave suggest that a bit more realism is in order.

Of course, we know very little of what went on at Moula-Guercy 100,000 years ago. Human flesh may have been a regular part of the Neanderthal diet. Or maybe the inhabitants of the cave were reduced to cannibalism by hunger or starvation. If so, they did nothing that we would not do ourselves.

In 1972 an airplane chartered by a young Uruguayan rugby team went down in the high Andes. Forty-five passengers and crew were on the plane, and all were eventually given up for lost. Then, miraculously, ten weeks later, 16 of the Uruguayans were rescued. They had survived in the snow-covered mountains by eating their dead.

A book about their ordeal, Alive, by Piers Paul Read, became a worldwide bestseller. After an initial shock, few readers second-guessed the survivors’ decision to cannibalize their friends. In Uruguay and the Vatican, church authorities affirmed the blamelessness of the boys’ actions. Read writes: “It had taken a supreme effort of the will for these boys to eat human flesh at all, but once they had started and persevered, appetite had come with the eating, for the instinct to survive was a harsh tyrant.”

The Donner Party stranded in the high Sierra Nevadas in the winter of 1846 – 47 also were driven to eat their dead by the harsh tyrant of starvation. In a long poem about that tragedy, Ruth Whitman writes in the imagined voice of Tamsen Donner: “Is this new continent/ a place where we can live/ only by thrusting down/ that fragile barrier/ the ancient loathing/ to eat each other’s flesh?”

The Neanderthals of Moula-Guercy may have been neither better or worse than ourselves when it came to the grim business of cannibalism. For all we know, they may also have shared the ancient loathing against eating our own that distinguishes us from lions and hyenas. We may be grisly folk when the need arises, but our instinctive respect for our dead — that “fragile barrier” — puts us squarely on the side of the angels.