Originally published 13 March 1995

I knew the moment I touched the doorbell that this interview was going to be different.

I was expecting an electronic voice welcoming me to the house. What I heard instead was a “ding-dong” ringing somewhere inside, such as you might have heard back in the 20th century.

It wasn’t long before Anna Logue appeared — an attractive gray-haired woman in a flowing dress. Astonishingly, she seemed completely disconnected from the Net.

I introduced myself. “I write a column for the Globe called Science Musings. Do you know it?”

She replied: “I stopped reading the Globe when it stopped printing on paper.”

I should have guessed. After all, that’s why I was there.

Anna Logue is president of Friends of Books, a small but fanatical group of people who collect and read paper books.

“Please come in,” she said.

I spoke briefly to my Wrist Processor. At my instruction, it began recording my conversation with Anna and transmitting a transcript via satellite link to my computer at home.

“I thought my readers might like to hear about your organization.”

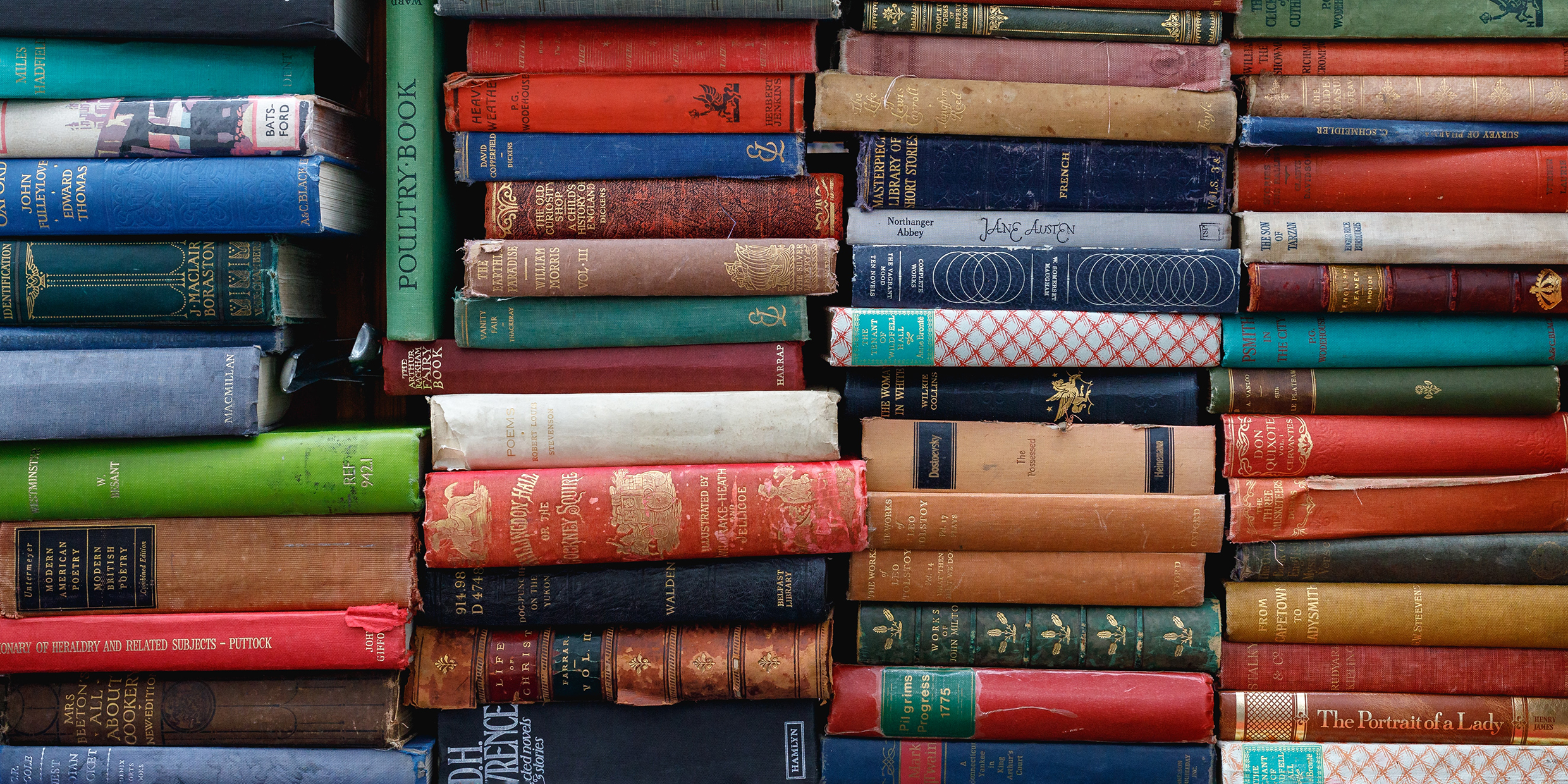

I glanced about the room. The walls were lined with shelves stuffed with books. No flat-panel video displays. No modems, no faxes. No electronic devices of any kind.

I took a book from a shelf: Being Digital, by Nicholas Negroponte.

“I remember this book,” I said, flipping it open. “Yes, published in 1995 by a professor at the MIT Media Lab.”

“Only 20 years ago,” said Anna, “but it seems like another age.”

“Ironic, isn’t it, that a manifesto of the digital future should have been published as a book?”

“And a handsome book at that,” she said. She took the volume from me and glanced at the publisher’s logo on the spine. “Alfred Knopf. They did quality stuff. Unfortunately, they were swallowed up in the late-90s by Microsoft Multimedia.”

“Funny that you should have a copy,” I said. I let my finger run along the spines of other books on her shelves — Austen, Dickens, Steinbeck, Morrison…

She replied: “Oh, it’s quite a charming book, actually. Sprightly, witty, fun to read.”

My Wrist Processor interrupted with an audio prompt from my Digital Personal Organizer. I downloaded a message, glanced at the display, then returned to the conversation.

“As I recall, Negroponte predicted that the digitization of culture would usher in a golden age of world harmony.”

“Hmmm — ,” mused Anna.

I took the book from her hands, turned to the last page, and read: “While the politicians struggle with the baggage of history, a new generation is emerging from the digital landscape free of many of the old prejudices. These kids are released from the limitation of geographic proximity as the sole basis of friendship, collaboration, play, and neighborhood…”

Anna gently interrupted: “We Friends of Books believe the ‘baggage of history’ is not all bad. We value things you can’t find on the Net. Solitude. Eccentricity. Vernaculars. Poetry.”

My Powerbelt beeped, indicating I was running on reserve power. If I lost my satellite link, I would have to take notes with pen and paper, neither of which I had.

“But surely Negroponte was right,” I protested. “The Net has harmonized the world. A common language has emerged, common hopes, common expectations…”

“Dead common,” said Anna, with a wry smile.

“Not true,” I said. “The triumph of digitization is freedom — freedom to watch precisely the entertainment, news, or sports that I want, when and where I want it. My toaster knows just how I like my toast; my word processor anticipates every quirk of my personal style. I can look out the electronic window of my house and see any landscape on Earth — the Alps, the rain forest — as I choose. It’s like Negroponte said: ‘Being digital is the triumph of the individual.’ ”

I must have been getting excited. The health monitor function of my Wrist Processor buzzed, indicating a rise in blood pressure.

“Being digital is the illusion of freedom,” said Anna, quietly. She took a book from a shelf. “Freedom is being disconnected from the Net. Freedom is the privilege of burning my toast, or of using an unexpected turn of phrase. Freedom is being able to curl up in bed with Thoreau’s Walden” — she tapped the volume in her hands — “or any other piece of the ‘baggage of history.’ ”

My Powerbelt beeped furiously, indicating an imminent loss of power. I hunched over almost double so that the Flexidish antenna woven into my shirt was pointed more directly at the invisible satellite out there in space. “How many members are there in your organization?” I urgently asked.

“Not many,” replied Anna.

“And where do you manage to find books, real paper books?” I swiveled, hoping for a stronger signal.

“Attics. Basements. We trade around. The last actual book was published in 2006.”

I beeped. I buzzed. I furiously tapped my Powerbelt.

She looked at her watch, a lovely antique thing with hands and numbers around the dial. “I’ll be saying goodbye,” she said as she guided me gently toward the door. “I’m getting quite tired of your being digital.”