Originally published 8 February 1988

In 1900 Henry Adams, American historian, quintessential Bostonian (born in the shadow of the State House), 62 years old, visited the Paris Exposition, a great world’s fair celebrating the end of Adam’s century and the beginning of a New Age.

Again and again Adams was drawn to the Gallery of Machines, where huge 40-foot dynamos spun at vertiginous speed, scarcely humming as they generated quantities of a silent, invisible new force — electricity.

Adams did not quite know what to make of the dynamos. He recognized he was in the presence of something of historical importance, but was baffled by his inability to find in these machines anything recognizably human.

He had spent fifty years educating himself. He had published a dozen volumes of history. But in the hall of the dynamos he was reduced to ignorance by forces that he could neither see nor understand. The great wheels spun, power surged through wires, and there was nothing he could detect with his senses. It was a profoundly humbling experience.

A pivotal moment

The encounter with the dynamos is a pivotal moment in Adams’ autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams. I was reminded of that episode recently as I read of the continuing controversies concerning the Superconducting Super Collider (SSC).

The SSC will be the largest, most expensive scientific instrument ever built. The cost will be over $5 billion, and peak construction will require a work force of 4500. Competition among the states for this hugely lucrative plum is intense. In early January the Department of Energy narrowed the number of potential sites for the machine from 36 to 8 — but pitched political battles are far from over.

If the machine is built, most citizens will stand before it like Adams before the dynamos. Five billion tax dollars will pay for the SSC, and only a small coterie of high-energy physicists fully grasps its purpose. For the rest of us, we have a sense that something important is going on, something that has to do with understanding the basic laws of matter, but exactly what it is eludes us.

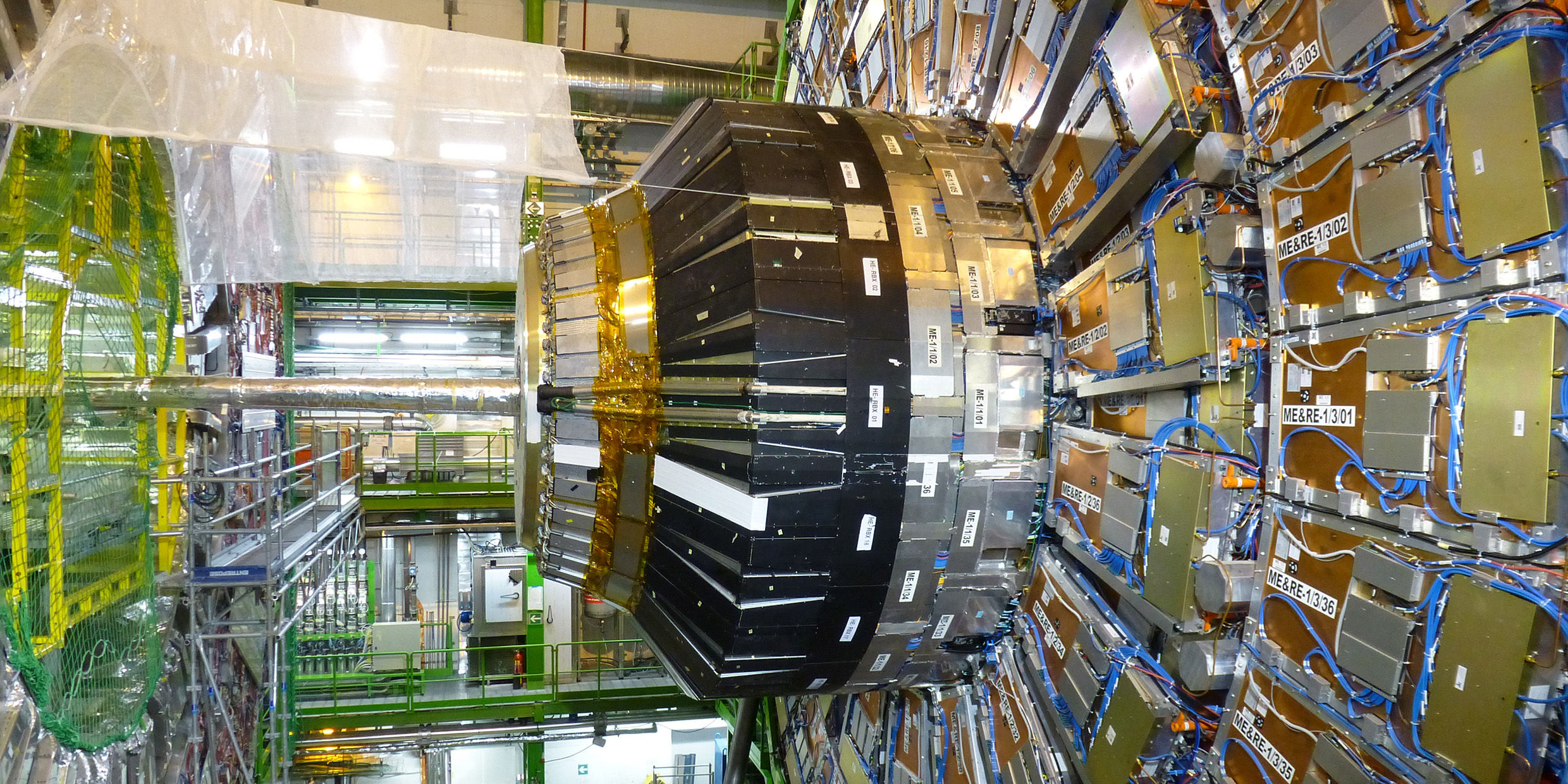

The SSC is a particle accelerator, twenty times more powerful than any now operating. Its purpose is to propel streams of protons to high energies, in opposite directions around a ring 53 miles in circumference. The protons will be held in their courses by supercooled magnets, and accelerated by pulses of radio waves.

When the protons are caused to collide head on, for a trillionth of a trillionth of a second a density of energy will be achieved such as existed in the first moment of the creation. Out of this energy rare particles are expected to briefly materialize that will help confirm or refute current theories for the origin of matter.

A differing of views

If you think this sounds a bit like angels dancing on the heads of pins, you may be right. There are those who say that physicists have followed their quest for the fundamental laws of nature into realms of space, time, and abstraction that have nothing to do with ordinary experience. According to this view, the high-energy physicists should be allowed to play their reductionist games, but need not be supported with a $5 billion instrument paid for out of the public treasury.

Others say that knowledge is an ultimate good, and that we must follow nature’s lead wherever it takes us. According to this view, the theories of physics provide us with a grand, unified vision of reality that encompasses the smallest units of matter and the most distant galaxies. The SSC is a kind of super-microscope that will let us examine the tiniest threads in the fabric of creation — and understand more fully what it is that binds all things together.

Supporters of the SSC sometimes compare the proposed machine to the great medieval cathedrals. In both cases, they say, a people have chosen to invest a significant part of their capital and talent in a quest for ultimate meaning.

I am not unsympathetic to the SSC, but I find the cathedral analogy specious. The cathedrals were places of public congregation. The soaring arches, the magnificent stained glass, the evocative sculptures touched — and continue to touch — the human spirit. The effect of the cathedrals is direct, immediate, and quite independent of the theological system they embodied. Even the hesitant Unitarian Henry Adams was sufficiently moved by his visits to Chartres and Mont-Saint-Michel to write a book about the experience.

The SSC, by contrast, will be built underground in a long tunnel. It will generate particles that will disappear from existence almost as soon as they appear, and whose fleeting reality will be inferred by a handful of specialists from a scatter of lines on the screen of a computer. Visitors to the SSC will be impressed by the sheer technological magnitude of the project, but most will come away slightly perplexed and — like Adams in the hall of the dynamos — wondering what it all means.

The construction of the Superconducting Super Collider (SSC) was cancelled in 1993. Europe’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC), completed in 2008, is currently the world’s largest particle collider. ‑Ed.