Originally published 6 June 1988

In November 1959 I received in the mail my first issue of Scientific American. I was a graduate student in physics at the time and my new spouse had given me a subscription to the magazine for my birthday.

The subscription approaches its 30th anniversary [in 1989]. During the intervening years, geology was revolutionized by the theory of plate tectonics, the “big bang” theory for the origin of the universe was substantially verified, spectacular progress was made in understanding the molecular basis of life, computers permeated every aspect of science and society, humans left footprints (and tire tracks) on the moon and sent probes to the outer reaches of the solar system — to mention just a few things that transpired in science. Throughout it all, Scientific American kept me (and thousands like me, both scientists and non-scientists) authoritatively informed.

The magazine is more than a commercial venture, it is an educational institution. Scientific American articles have probably been more frequently assigned as required readings for high school and college students than materials from any other source. The bibliographies of many science textbooks are little more than lists of articles from the magazine. Packages of reprints have served as the text for many college courses. Bound collections of articles have a prominent place on the reserved reading shelves of school libraries. And finally, the magazine may be the single most important vehicle for keeping scientists informed about developments in fields significantly different than their own.

The extraordinary contribution of this particular magazine to science education is seldom acknowledged. I am one reader and educator who would like to say “Thanks.”

A long history

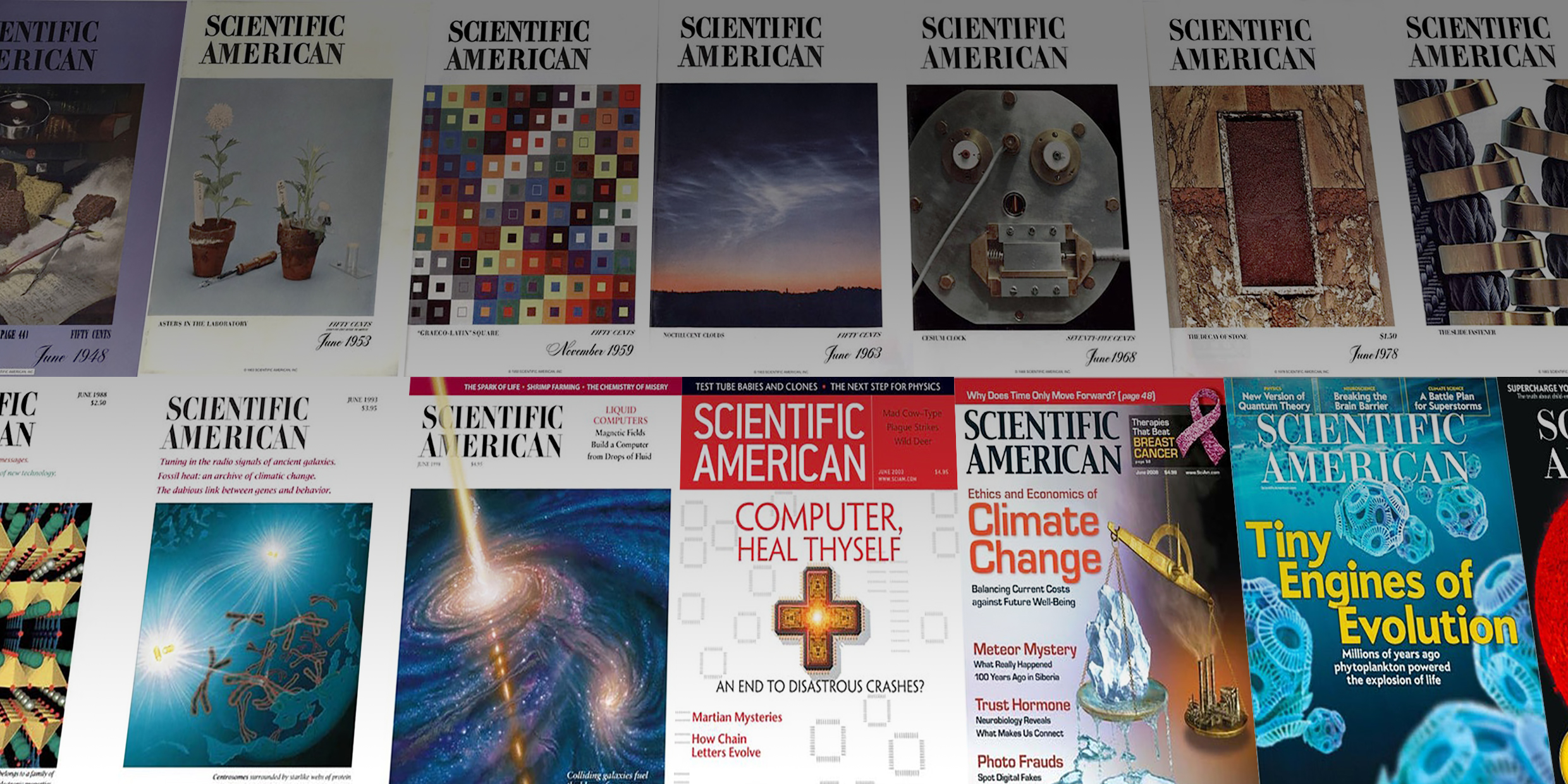

There has been a Scientific American for 143 years, but for most of its history the magazine concerned itself with the horse-sense application of science to industry. Perusing early issues of the magazine is like thumbing through catalogs of inventions. The current journal got its start in 1948, when Gerard Piel and his associates purchased “the name, good-will, and circulation” of the old magazine, and changed its focus from practical technology to science.

In its current format, Scientific American is celebrating its 40th anniversary. The original prospectus promised that the new magazine would fill a gap between two kinds of science communication — the technical journal in which the specialist reports his work to other specialists in the same field, and the popular magazine of science published for mass audiences. The new Scientific American targeted its audience in the gap between the two extremes, “the growing community of US citizens who share a responsible interest in the advance and application of science.”

It is to the credit to the original editor and publisher, Gerard Piel, that he saw a gap and filled it. Admirably. After four decades, Scientific American has this particular niche in scientific communication virtually to itself. The magazine offers scientists a way to communicate with other scientists in different fields, and with that part of the general public who want to push their curiosity and knowledge beyond what can be found in the popular press.

The authoritativeness of Scientific American stems from the fact that the articles are written by the experts who did the work. Scientific specialists are not usually noted for the lucidity of their prose, so it is something of a miracle that the magazine works at all. It works, it seems to me, for two reasons. First, the editors skillfully insure that the words that reach the pages of the magazine are plain English. And second, the magazine’s graphics are simply the best there are.

Informative images

I think it is fair to say that Scientific American has redefined the nature of scientific illustration. The style is both dignified and beautiful. No matter how abstruse the subject — particles physics, protein structure, the stress analysis of Gothic cathedrals — the graphics take you right to the scientific heart of the subject.

My first issue of Scientific American, back in 1959, contained articles on high-energy cosmic rays and the language of crows. The June 1988 issue has articles on bacteria as multicellular organisms and early iron smelting in Central Africa. Multiply that diversity of subject matter by 2,780 (nearly 30 years of articles) and the magazine has covered a lot of ground since I’ve been a subscriber. I can truthfully say that I have learned more general science from Scientific American than from any other source.

Which is why a shiver of worry went up my spine a year or two ago when I read that the magazine had been purchased by a German publishing group, amid reports of takeover battles and financial distress. Scientific American is a resource that science education can ill afford to lose. Was this the beginning of the end?

From the looks of it, the answer is no. Editor Jonathan Piel, Gerard’s son, remains in charge. There have been recent changes in format that make the magazine sprightlier, newsier, and easier to read. To my mind the changes are all to the good.

But it would be a shame to tinker too much with a formula that has served science education for so long with such effectiveness. If we are lucky, we’ll have forty more years of the same old-faithful magazine. Happy anniversary, Scientific American, and many happy returns.

Scientific American celebrates its 175th birthday in 2020. ‑Ed.