Originally published 19 January 1987

In October 1347, a fleet of Genoese merchant ships from the Orient arrived at the harbor of Messina in northeast Sicily. All aboard the ships were dead or dying of a ghastly disease. The harbor masters tried to quarantine the fleet, but the source of the pestilence was borne by rats, not men, and these were quick to scurry ashore. Within six months, half of the population of the region around Messina had fled their homes or succumbed to the disease. Four years later, between one-quarter and one-half of the population of Europe was dead.

The Black Death, or plague, that devastated Europe in the 14th century was caused by bacteria that live in the digestive tract of fleas, and in particular the fleas of rats. But at that time, the disease seemed arbitrary and capricious, and to strike from nowhere. One commentator wrote: “Father abandoned child, wife husband, one brother another, for the plague seemed to strike through breath and sight.” The pestilence was widely held to be a scourge sent by God to chasten a sinful people.

The disease AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) has been called the modern plague. The analogy may be extreme, but the potential for disaster is enormous. Nine thousand Americans died of AIDS during 1986, doubling the cumulative total at the beginning of the year. During 1991 there may be more than 50,000 deaths in the United States, mostly from among the more than a million people already infected. If no remedy is found, the social effects of the disease before the end of the century may indeed begin to resemble those of the Black Death.

There is another analogy between AIDS and the Black Death. Presently, the highest-risk groups in this country include male homosexuals and intravenous drug users. Some observers see in this a sign of divine retribution for unacceptable social behavior. Homosexuals, in particular, have been made scapegoats for AIDS, as in medieval times Jews were charged with infecting the wells and corrupting the air. Blaming any group of AIDS victims is reprehensible and without foundation. In Haiti and many African countries, women and men are more equally infected, and the disease is apparently transmitted as readily by heterosexual as by homosexual contact. Like the Black Death, AIDS has the potential to set wife against husband, husband against wife, lover against lover, one citizen against another.

Scientists worked quickly

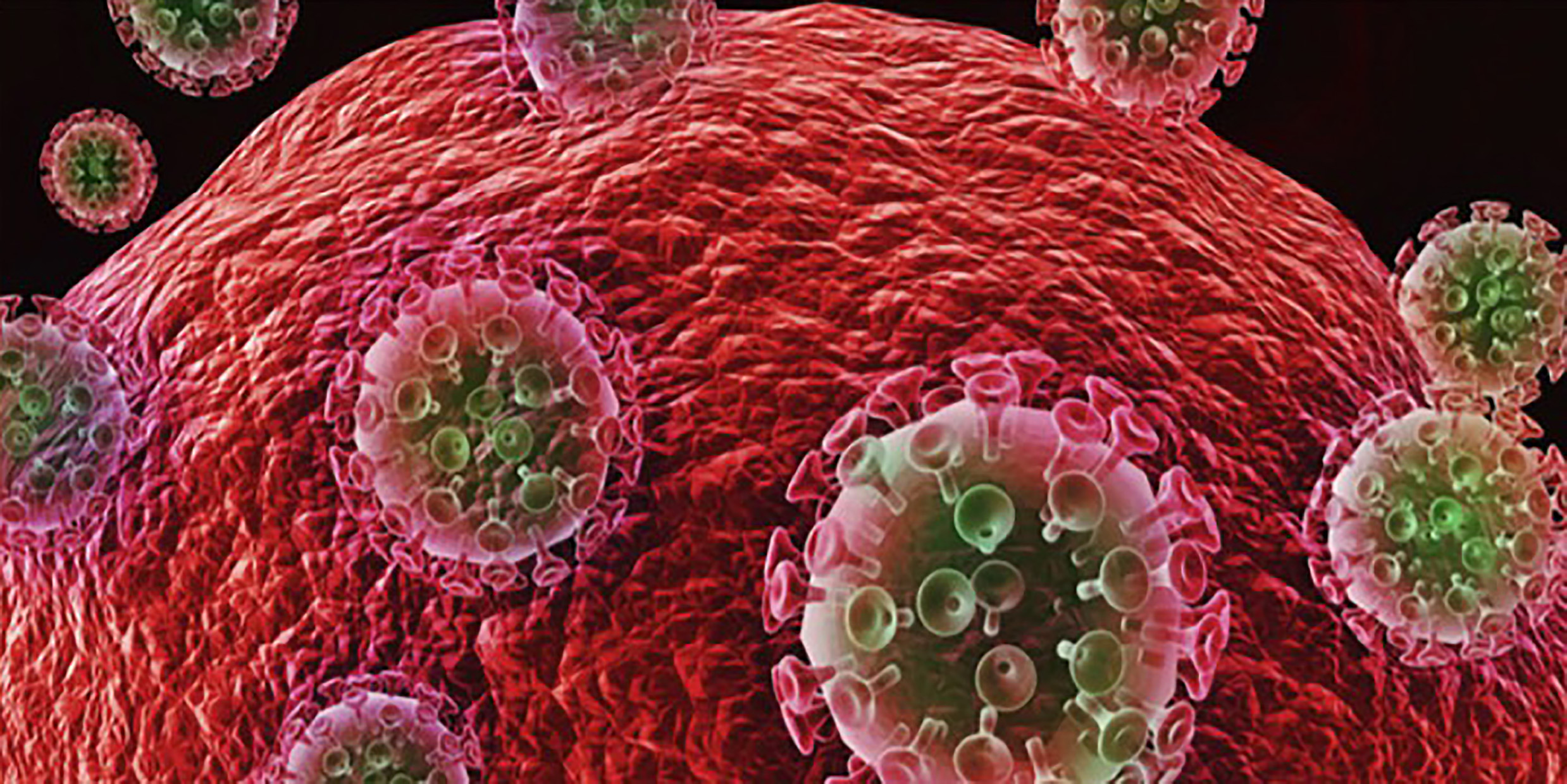

And what is the cause of this modern scourge? The agent of the disease has been identified with remarkable quickness. In 1984, only three years after the disease was first described, its cause was shown to be a virus, now variously called human T‑lymphotropic virus III (HTLV-III) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). A schematic portrait of the virus, enlarged a million times, adorns the cover of [the January 1987 issue of] Scientific American.

I have returned to the cover illustration again and again. It is a simplified rendering of the overall architecture of the virus. One might expect that the agent of so pernicious a disease would itself be unlovely. But HIV is a thing of spare elegance, with the delicacy of a flower and the symmetry of a snowflake. It has no foul aspect. It is starkly and simply beautiful.

One hundred million HIV viruses could fit on the head of a pin. Small almost beyond imagining, their influence can be devastatingly macroscopic. The virus does not act by malicious intent, but as an inevitable consequence of its chemical structure. It is simpler than a cell, but like all living cells, including the cells of our own bodies, it is programmed for self-replication. When we look at the cover illustration of HIV we are looking at the bare essence of life, the foundational molecular machinery that animates the world. The proper response, it seems to me, is not revulsion, but awe.

The spherical outer envelope of the virus is a fatty membrane studded with proteins. Other proteins form inner structures that contain the genetic material, in the form of threadlike RNA molecules, and an enzyme called reverse transcriptase. Like other viruses, HIV inhabits a domain somewhere between the animate and inanimate. It bears the information necessary for self- replication, but cannot reproduce on its own. Reproduction is possible only when the virus invades a living cell and exploits the reproductive machinery of the host.

Small beyond imagining

When HIV enters a host cell, the reverse transcriptase enzyme uses the RNA as a template to assemble a corresponding molecule of DNA. The DNA inserts itself into the genetic material of the host cell, usually one of the white blood cells of the human body that are crucial to the body’s immune system. The virus may remain inactive inside the host cell for some time, but when it is stimulated to activity, perhaps by a secondary infection, it reproduces so vigorously that it kills the host. The killing of white blood cells leaves the body open to infection by other agents.

The history of the Black Death holds a lesson for today. AIDS will not be conquered by assigning scapegoats or by repressive legislation. In the article that accompanies the Scientific American cover, Robert Gallo, one of the chief researchers responsible for identifying HIV as the cause of AIDS, says this of the disease: “Until a reliable vaccine is developed, intelligent caution and an understanding of the virus are the best weapons against its spread.”

Deaths from the HIV/AIDS pandemic peaked in the United States during the mid-1990s. Infections and fatalities in the US have dropped considerably since that time as education, prevention, and new medical treatments have controlled its spread. In other parts of the world, especially Africa, the disease continues to bring misery and death to far too many. ‑Ed.