Originally published 2 November 1987

Someone asked me the other day why I never write about chemistry in this column.

I’ll tell you why. Chemistry is boring. Chemistry is the plain step-sister of science, the Cinderella who is never asked out, the child of dust and ashes. Physics and biology are the glamorous sisters, all dolled up in their fancy gowns and flashy jewels.

Physicists pursue “fundamental” laws of nature. Biologists study the wonders of life. And what does chemistry have to offer? Molecules. Just molecules.

Physicists are about to spend several billion dollars on a superconducting supercollider, a stupendously expensive machine designed to explore the subatomic world of quarks, squarks, gluons, gluinos, and other exotic particles that, if they exist at all, live for an unimaginably tiny fraction of a second, flitting in and out of existence like faint intimations of some ultimate mystery.

Biologists are embarking on a multi-billion dollar project to completely map the human genome, the vastly complex genetic blueprint for what makes me me and you you. Meanwhile, the chemists go on building funny little models of molecules with ten-dollar sets of knobs and sticks, like Tinker Toys, and initiating one more generation of reluctant students into the fine art of ho-hum.

A little magic

But wait! Along comes a book by British chemist P. W. Atkins, called simply Molecules, one of the Scientific American Library of fine books. Atkins’ subject is as old as freshman chemistry. There is nothing in the book beyond what used to put us to sleep in Chem 101. Nothing, that is, except a little magic. With flair and imagination, Atkins succeeds in reminding us that the chemist’s Tinker Toy set is a remarkable toy indeed.

The molecules of Atkins’ book consist of only eight kinds of atoms. Glad-handing hydrogen. Gregarious carbon. Narcissistic nitrogen. Promiscuous oxygen. And few exotic hanger-ons: fluorine, phosphorus, sulfur, and chlorine. Eight kinds of little knobs that stick together in characteristic ways, each so small that a million million might comfortably sit on the period at the end of this sentence. No child’s construction set could be simpler. No child’s construction set is so rich with possibility.

Atkins offers for our consideration 160 molecules, each portrayed by a colorful schematic drawing and described by a provocative little essay. The molecules he picks are a personal choice, but all play a familiar role in our lives. Most are composed of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen.

There is water, of course, an oxygen atom holding hands with two hydrogens. It’s an odd little molecule. One might expect so slight a thing to be a gas at ordinary temperatures, but no, it’s a liquid, and lucky for us that it is; life would be impossible without it. Replace the oxygen atom in water with an atom of sulfur and the liquid of life becomes hydrogen sulfide, a noxious, foul-smelling gas.

And ethanol: a puppy-shaped molecule, with two carbons for a body, an oxygen head, and five hydrogens for nose, feet and tail. Our prehistoric ancestors discovered the intoxicating effect of this arrangement, and it has been a common ingredient of social drinking ever since, sometimes with a dash of water. Detach the nose and one leg from the “puppy” and you have acetaldehyde, a chemical responsible for hangovers.

Some simple molecules have unfamiliar names, but familiar roles. Butanedione has four carbons, six hydrogens, and two oxygens: It is instrumental in the odors of fresh butter and stale sweat.

Mixing and matching atoms

There’s no end to the ways these three kinds of atoms can work together. Start with nineteen carbon atoms, twenty-eight hydrogens, and two oxygens, and let them fall into a sort of fat-caterpillar clump and you have testosterone, the male sex hormone. Snip one carbon atom and four hydrogens from the caterpillar’s tail, and with a slight rearrangement the result is estradiol, a principal female sex hormone.

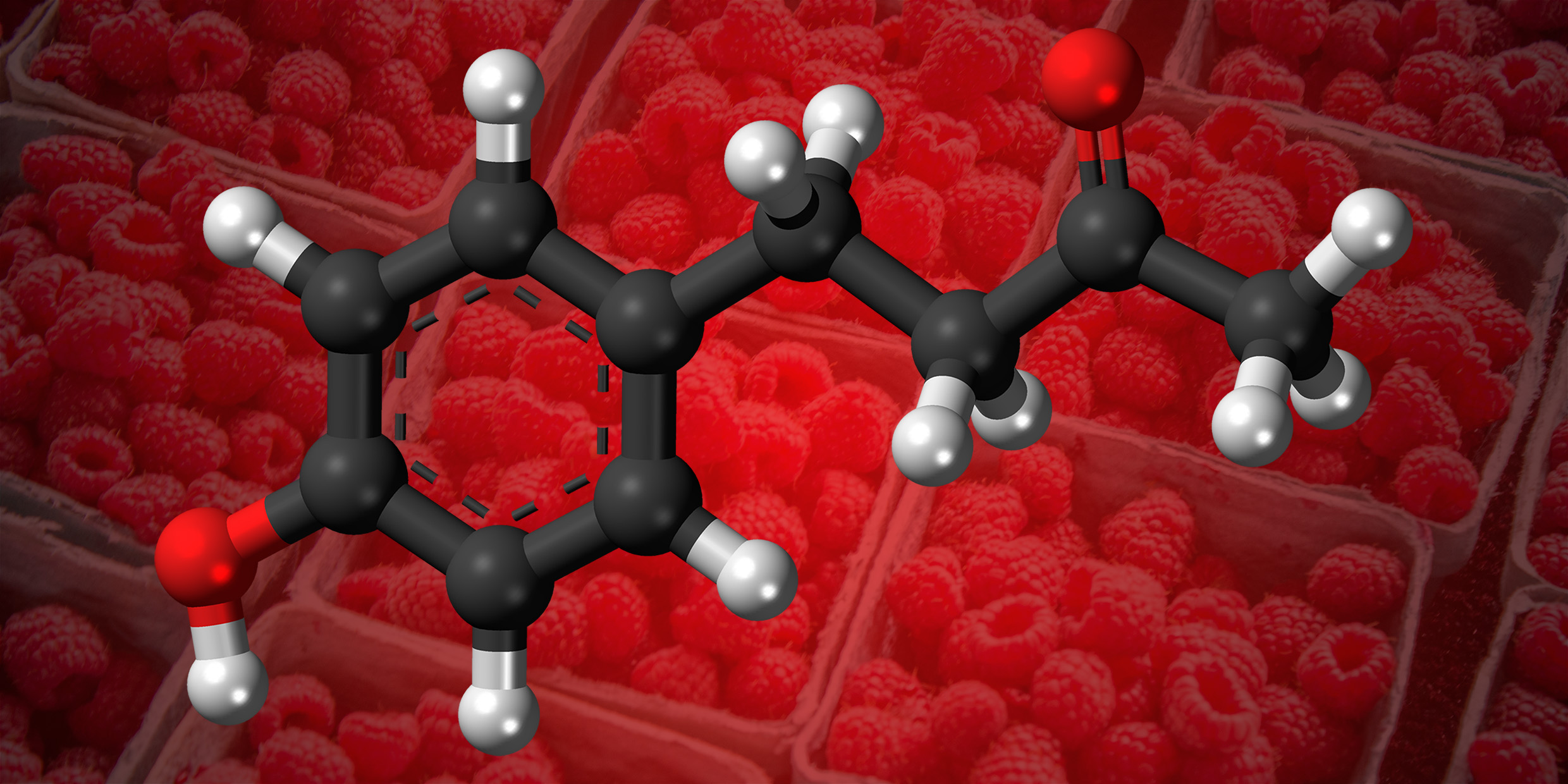

Subtract three more carbons and a baker’s dozen of hydrogens, toss in a few oxygens, let the whole thing settle down into a new arrangement, and you have pelargonidin, a chemical that gives color to autumn leaves. Whittle that assembly down still further, to ten carbons, twelve hydrogens, and two oxygens, and you have 4-(p-Hydroxyphenyl)-2-butanone, better known as the smell of ripe raspberries. Chop off two more carbons and four hydrogens, add an oxygen, jiggle into place, and you have delicious vanillin.

What a set of Tinker Toys! What an amazing variety of things from such simple arrangements. Molecules that burn, and molecules that extinguish fire. Molecules that cause pain, and molecules that are pain killers. The yellow of carrots and the pink of flamingos. Cellulose and TNT. Cannabis and mustard gas. Touch, sight, taste, smell. The mysteries of sex. Pleasures and poisons. As Atkin’s says: “The world and everything in it is built from the almost negligible.”

We need to be reminded that matter, ordinary matter, is mysterious and magical. The smell of fresh raspberries, the flaming hillsides of New England in October, the pleasurable rush of sexual desire. Molecules. Just molecules. Physicists and biologists take note: In Atkin’s delightful book the Cinderella of chemistry begins to look a lot like a beautiful princess.