Originally published 21 March 1988

Ever since I started working on this column my eyelids have been itching, and I’ve been involuntarily scratching at my wrists and the gaps between my fingers. It may be psychologically induced, but I swear that I feel them—the invading hordes, the microscopic monsters, the aliens.

The trouble began when I read two new books on the world of the microscopic: Microcosmos, by Jeremy Burgess, Michael Marten, and Rosemary Taylor, published by Cambridge University Press, and The Secret House by David Bodanis, published by Simon and Schuster. Both contain state-of-the-art images of objects too small to be seen with the naked eye, made with several microscope technologies. Most spectacular are the crisp, “three-dimensional” images produced by the scanning electron microscope (SEM).

On the first page of Microcosmos we are offered four SEM micrographs of the point of a common household pin. The first is enlarged 30 times. We see tiny striations on the sides of the pin, but the pin looks otherwise familiar — shiny, smooth, tapering to a slightly blunted point. In the second image, magnified 150 times, the pin seem to be dusted with orange snow. The third picture (750×) shows what appear to be tiny climbers struggling to attain the summit of a flat-topped mountain. In the fourth micrograph (3750×) we see the “climbers” for what they are — capsule-shaped bacteria clinging to rills in the side of the pin, the kind of bacteria that might cause a scratch or pinprick to become infected. The effect is beautiful and terrifying.

A scanning electron microscope works in a different way than an ordinary light microscope. Electrons from an electron gun are focused to a fine point on the surface of the specimen. The impact of the beam causes secondary electrons to be ejected from the specimen. These are collected and turned into an electrical signal that produces a dot on a video screen. By rapidly scanning the beam across the specimen in a two-dimensional pattern, a picture of the specimen is displayed on the screen.

Stunning fidelity

Electron microscopes are complex and expensive, but they have one great advantage over light microscopes. Electrons traveling in a vacuum can be considered a kind of radiation of extremely short wavelength. Because electron wavelengths are shorter than those of visible light it is possible to achieve higher levels of magnification — and see the world of the very small with stunning fidelity.

And what wonders there are to be seen! Here are images of everything from computer microchips to eggs in the human ovary, from diamond styluses wriggling their way along grooves in phonograph records to pollen grains in flowers. But of all the astonishing images in these books, I found most fascinating the living creatures that share my personal space.

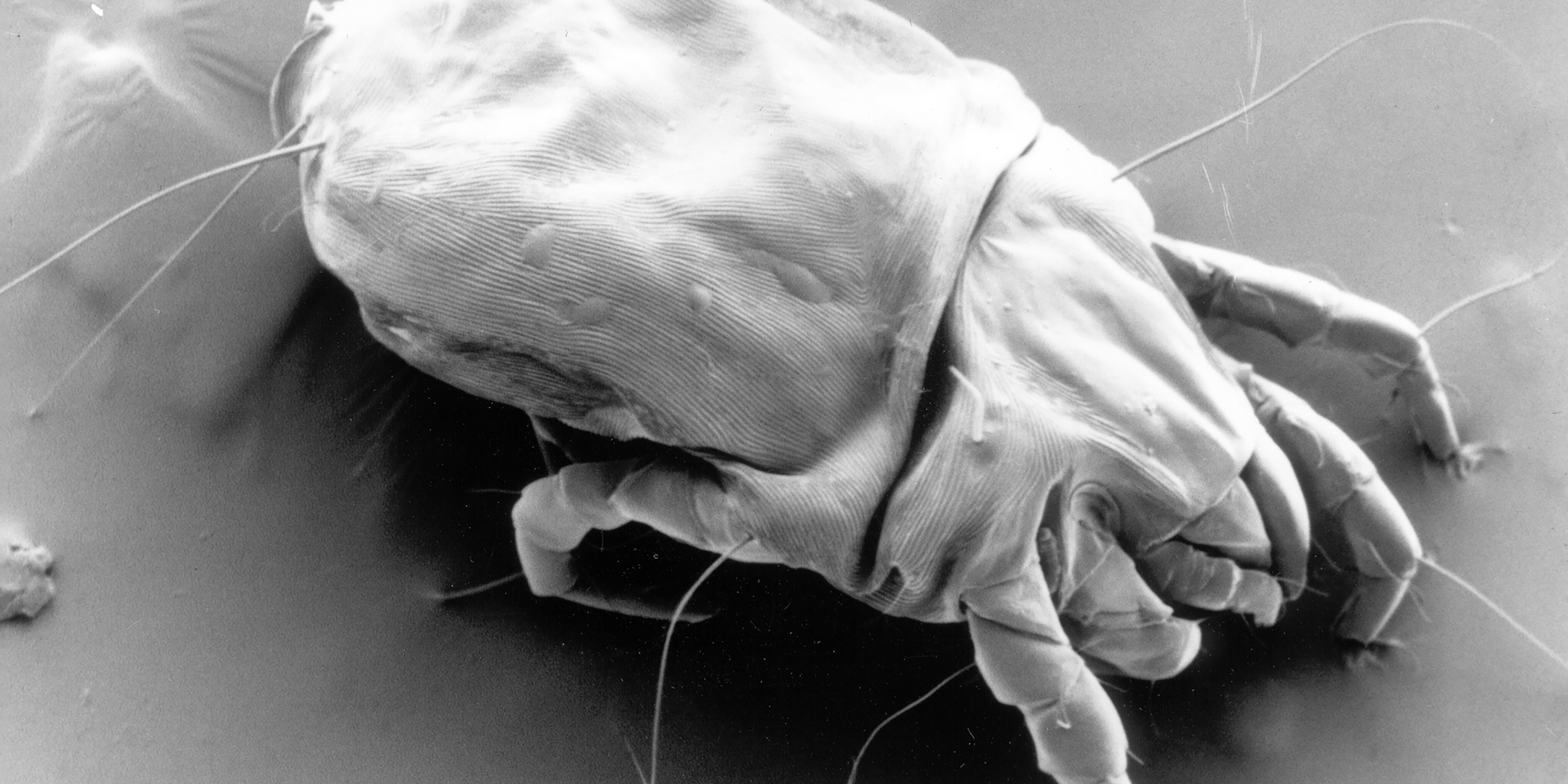

Consider the two-page spread in Microcosmos of household dust, dumped from a vacuum cleaner bag and magnified 145 times. Dirt grains the size of boulders. Clothing fibers and strands of hair twisted together like jungle vines. Fragments of skin as numerous as fallen leaves. And in the midst of this detritus a dust mite, a monstrous, scaly creature from the age of dinosaurs, Godzilla of the carpet.

Every gram of household dust contains upwards of a thousand mites. They thrive on sofas and mattresses — more than a million in a typical bed! — feasting on flakes of skin that fall from our bodies like an unceasing manna from heaven. Both books give us close-up portraits of a dust mite’s ugly head, bristling with tiny hairs and bracketed by serated claws, a fiercesome visage that belies the creature’s docile, passive nature.

Mites not only share our beds. Another species, the follicle mite, lives, mates, and breeds among our eyelashes, and in the cave-like hair follicles of our noses and chins. Neither book has a photo of a follicle mite, but there are enough images of their cousins — including a prickly, many-clawed louse clutching a human hair — to set the fingers scratching. One sequence of micrographs in The Secret House shows a flea with a colony of mites happily ensconced under the scales of its back — a consoling reminder that we are not the only species who bear a burden of invisible bugs.

Visitors to small planets

Mites are invisible to the eye, but they are still hundreds of times bigger than bacteria. Bacteria are the dominant inhabitants on the human skin by virtue of sheer numbers — millions per square centimeter in the tropical forests of the armpits, hundreds per square centimeter in the dry deserts of the back. To bacteria, our bodies are small planets that offer a wide selection of inviting habitats.

Most numerous of all the bacteria which share our bodies are the Escherichia coli, who inhabit our intestinal caverns in prodigious numbers. If the E. coli in my body were laid end to end they would reach from Boston to San Francisco. They are mostly benign guests, doing me very little harm. Microcosmos has a number of fine pictures of E. coli—just lying there like little sausages doing nothing, having sex (such as it is), and reproducing. One startling picture shows an E. coli bacterium with a weakened cell wall spilling out its DNA, a twisted tangle of genetic “string” a thousand times longer than the bacterium itself.

These books are delightful introductions to the world of the very small. Of the two, I liked Microcosmos best; the micrographs are more numerous, more spectacular, and more crisply printed. A technical appendix describes in fascinating detail the operation of the various microscopes and preparation of specimens.

But if you are squeamish about sharing your space with burgeoning bacteria, bristly dust mites, and crab-clawed lice, then perhaps these pictures of things normally unseen are not for you.