Originally published 24 November 1986

By now you may have heard the joke. Question: What do you get when you cross a firefly with a tobacco plant. Answer: A cigarette that lights itself.

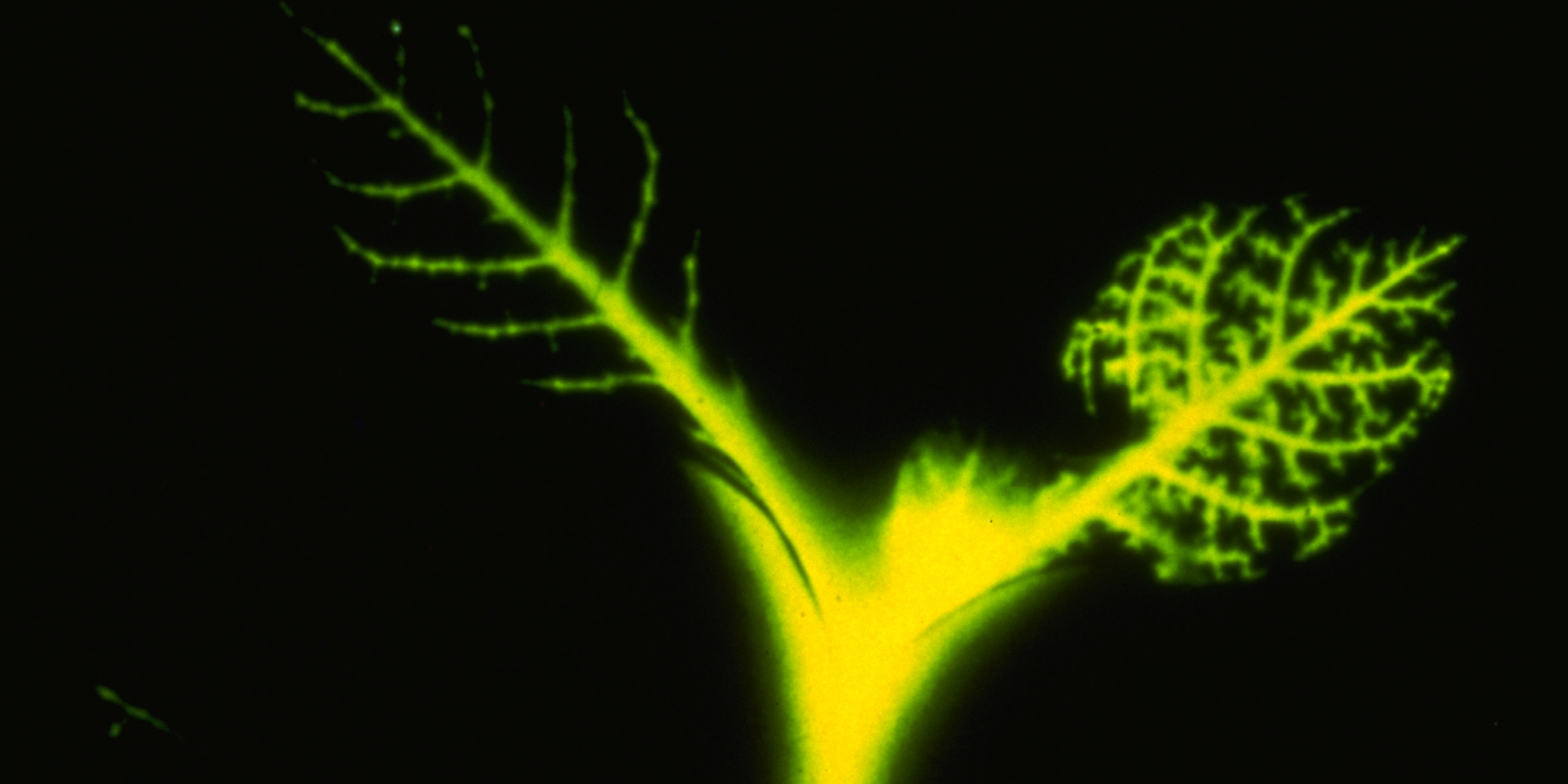

The joke quickly made the rounds after a group of genetic engineers in California earlier this month announced that they had transferred into the cells of a tobacco plant the gene that causes a firefly to glow. In the November 14 [1986] issue of Science there is a stunning photograph that illustrates their success. The picture shows a small tobacco plant — roots, stem, and leaves — glowing with an eerie firefly light.

To make the autoluminescent tobacco, the researchers first isolated the firefly luciferase gene, the DNA segment that gives rise to an enzyme that is the catalyst in the firefly’s light-producing chemistry. The firefly DNA was then introduced into the cells of tobacco plants. The plants were watered with a solution of the chemicals necessary for the luminescent reaction. The plants then emitted a faint but detectable light. To make the photograph that was reproduced in Science, a genetically altered plant was placed in contact with photographic film for 24 hours. The result is a beautiful scientific document that qualifies as a work of art.

One hardly knows how to react to a story such as this. One admires the knowledge and skill that enabled the genetic researchers to achieve such a remarkable transmutation of living matter. And one acquires a new respect for the chemical machinery of life. Still, I have returned again and again to the photograph in Science with a sense of foreboding. The tobacco plant seems to rise out of the page like a will‑o’-the-wisp or friar’s lantern, one of those flickering phosphorescent lights that are seen over marshes at night, and in folk legend sometimes beckoned unwary followers into the mire.

Benefits lie ahead

Certainly, the California researchers do not consider their experiments in genetic transmutations frivolous or dangerous. They are confident that the firefly gene can be spliced with other genes and used as a valuable marker in genetic experiments. Genetic researchers need to know quickly if and where transplanted genes have been activated. The firefly’s flash of light, issuing from the cells of another organism, can be the ideal signal.

And there is little doubt that this sort of experiment can lead to discoveries of benefit to humans. Grains that are resistant to disease, fruit trees that defy frost, bacteria that eat oil spills, vaccines for the cure of animal and human diseases — all of this and more is promised by genetic engineers.

So what is the source of my uneasiness? Genetic engineering is not the first breakthrough in science or technology that held a potential for danger as well as good. The invention of machinery for the mass production of goods and the harnessing of atomic energy are other examples that come to mind.

The worst excesses of the factory system — sooty cities, child labor, industrial diseases — have been largely eliminated by progressive legislation. The dangers of the atomic age are still with us in the form of terrible weapons of destruction, but at least we have the hope that what we have made can be disposed of when we enter more enlightened times. But a gene is a rather different thing from a factory or a bomb. A gene reproduces. A gene copies itself into the fabric of life. A gene is potentially immortal.

We are reminded of the vigor and resourcefulness of genes by the AIDS crisis. The disease AIDS is caused by a virus, a snippet of genetic material in a coat of protein. A virus is not quite alive, nor is it quite dead. It cannot reproduce on its own, but only in a host cell. A virus is a small gang of renegade genes, a deadly string of chemical code with a singleness of purpose — to replicate itself whatever the cost to the host organism.

Proceed with caution

In a virus we have an example of genes run amuck. Engineered organisms have the same potential for harm. Governments worldwide are hastening to establish regulations that will restrict the release of genetically altered organisms into the environment. In recent months, there have been several controversies involving the unauthorized field testing of engineered organisms.

At the same time, it is important to remember that genetic research may be the key to finding a cure for AIDS and other viral diseases. The soft phosphorescent light of the genetically altered tobacco plant beckons us toward a bright future of health and plenty. It also has a spooky Frankensteinian quality that warns us to proceed with caution.

As I look at the photograph in Science, I am reminded of sultry summer nights in Tennessee when we children ran barefoot through the grass of the long sloping lawn catching up fireflies in our hands. We may have squeezed them a few times, to set their little gene-activated fires alight. But we squeezed gently, and then we released the insects to take their place again in the live constellations of the summer night. We recognized, if only in a child-like way, that there is an integrity and a balance to life on Earth that demands of the dominant species a measure of restraint.