Originally published 17 July 1989

Where were you at 4:17 p.m., on Sunday, July 20, 1969?

It was the summer of Woodstock and Chappaquiddick. The Six-Day War and Hurricane Camille. The Charles Manson murders and the Sexual Revolution.

The best-selling books were Jacqueline Susann’s Love Machine and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint. Blood, Sweat & Tears had the top album; “Spinning Wheel” was their run-away single. Top grossing films were The April Fools and True Grit.

John Wayne and Elvis were still on earth, and two American astronauts were on the moon. The words flashed from the surface of the moon to the NASA antenna at Honeysuckle Creek near Canberra, Australia, then to the Comsat satellite over the Pacific and around the world: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

During the summer of 1969 I was touring Europe in a Volkswagen camper with my spouse and three young kids. On the afternoon of July 20 we drove into Copenhagen and tried unsuccessfully to find a hotel with a television. At the moment Eagle touched down on the dusty surface of the moon we were standing on a sidewalk outside a television shop with a crowd of itinerants, mostly young Americans with backpacks. Beyond the plate glass window, on the flickering screens of a dozen TV sets, history was in the making. A great cheer went up, a cheer of national pride, but more than that — for it wasn’t just Americans cheering — it was a cheer of pride for a great triumph of human imagination.

A tumultuous decade

The summer of ’69. The end of a tumultuous decade. The best of times and the worst of times. A time of glory and a time of shame. Inauguration and assassination. Camelot and My Lai. Marian Anderson on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and the bullet-torn body of Martin Luther King on a motel balcony in Memphis. It was a time when an ancient fabric of society began to unravel, and a time when blacks, women, environmentalists, and anti-war activists struggled mightily to knit a new fabric to replace the old.

Today we look back 20 years and try to evaluate what happened during the decade of the Sixties. Some see it as a time of liberation; others as a time of chaos. And what of Project Apollo, the greatest scientific and technological achievement of the century, perhaps of all time? What is the legacy of Apollo?

On the evening of July 20, 1969, I made a special effort to put my kids in front of a television set because I believed that what they would see was of epic importance. Now the flight of Apollo 11 has faded from their memory, and even from their consciousness. If they were asked to list the historic events of the Sixties they might mention the music of the Beatles, the assassination of John Kennedy, and the Vietnam War. The landing on the moon is forgotten.

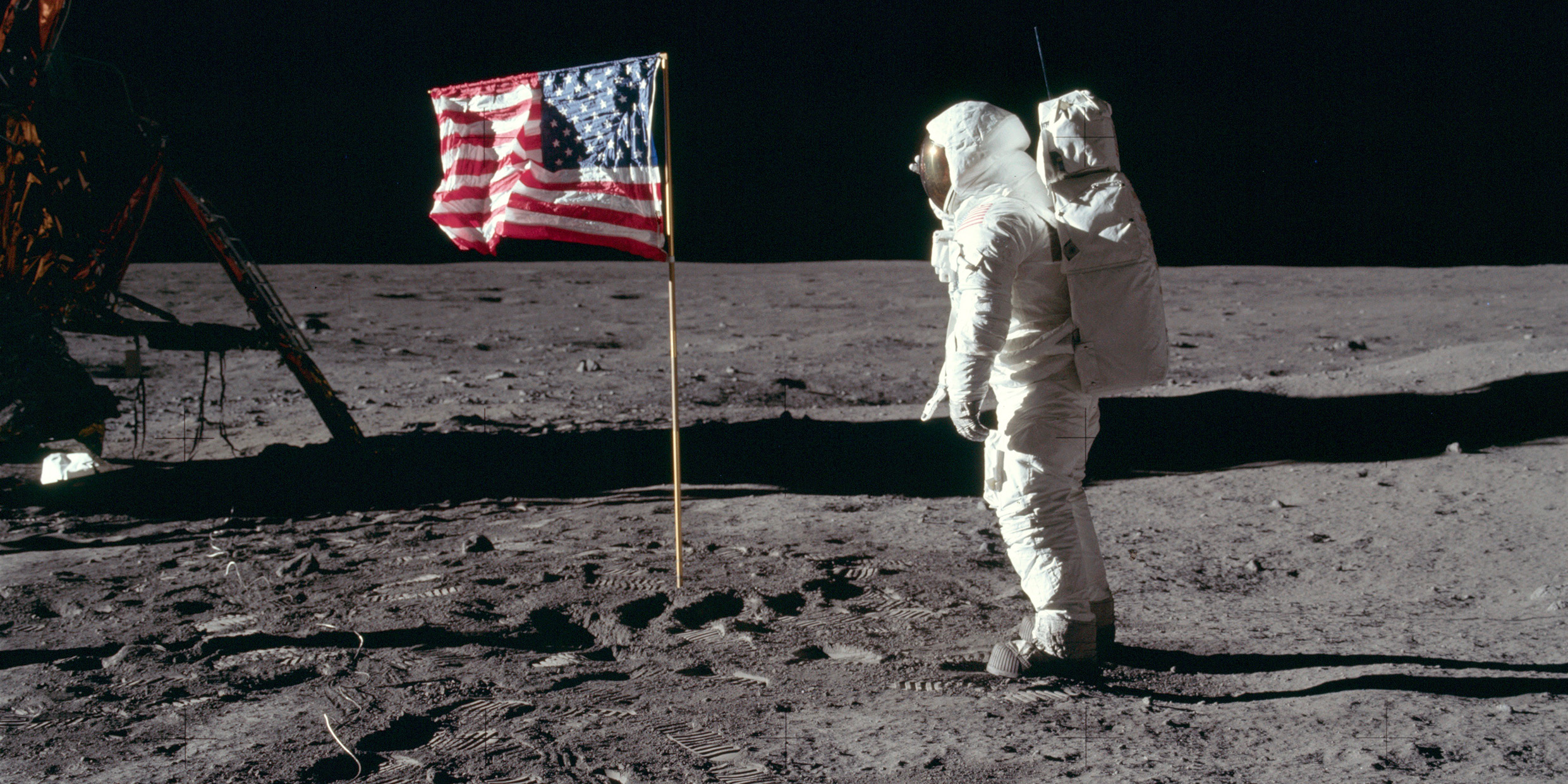

Even in my own mind the flights of Apollo seems unreal. Were they something that really happened, or something imagined? Those stunning images – the American flag reflected in the visor of Buzz Aldrin’s space helmet, the footprints in moon dust, Eugene Cernan driving the Rover, geologist Harrison Schmitt dwarfed by a lunar boulder, the blue-white planet Earth rising on the horizon — are like scenes from a vaguely remembered movie, or snapshots from someone else’s family album.

The June/July [1989] issue of the Smithsonian’s Air & Space magazine is devoted to a look-back at Apollo. It is a provocative issue that forces us to confront the real meaning of the adventure.

Not least among the lessons of this retrospective look at Apollo is the discovery that “the giant leap for mankind” was a fluke, a one-shot, never-to-be-repeated, feel-good stunt, a space Woodstock. The motive for going to the moon was political, a counter to Sputnik and Yuri Gagarin, a ploy in the battle of the superpowers for the hearts and minds of peoples.

Faced with a dilemma

“Kennedy wasn’t terribly excited about doing it,” recalled Jerome Wiesner, JFK’s chief science advisor (in an Air & Space article by Wayne Biddle); “but he was faced with a dilemma…The pressure on him was enormous from the public. He used to press me, saying, ‘Can’t you find something to do here on Earth that would use the money more effectively?’ And I said, ‘Not with the same political effect.’ ”

The goal was limited. “Get there, pick up some rocks, come home,” is how Biddle puts it. By 1972, after six successful moon landings, it was time to cut and run. The political agenda was complete; the epic human undertaking was relegated — by the politicians, perhaps by the citizens themselves — to the trash heap of history.

Twenty years after Christopher Columbus “touched down” in the Bahamas, Europe and the Americas had been irreversibly transformed, for good and bad. Twenty years after the Apollo landing on the moon, the episode is mostly forgotten — a sci-tech extravaganza in the service of superpower competition, a brilliantly-executed Camelot pageant.

However we evaluate the legacy of Apollo, this much is clear. The day will come — perhaps in decades, perhaps in a century — when flight to the moon will be commonplace. Tranquility Base will be visited as a historic shrine of space exploration, as today we visit Plymouth Rock.

It will all still be there, the detritus of the miracle: the Eagle’s descent stage, a TV camera and tripod, an array of scientific instruments, an equipment bag with cameras and tools, two life support systems, a gold olive branch symbolizing peace, the US flag unfurled on its staff, the footprints in the dust.