Originally published 24 July 2001

I have a biologist colleague who knows what a fellow likes. As a retirement gift, she gave me a bottle containing a few ounces of water, some algae, assorted microscopic organisms, and — wonder of wonders! — a few tardigrades.

She knew I would be appreciative. On a few occasions over the years, I had mentioned to her how much I would like to see a tardigrade in the flesh. These little creatures, about the size of the period at the end of this sentence, are adorably cute in microphotographs. And here they were, cavorting like playful otters in the field of view of my microscope.

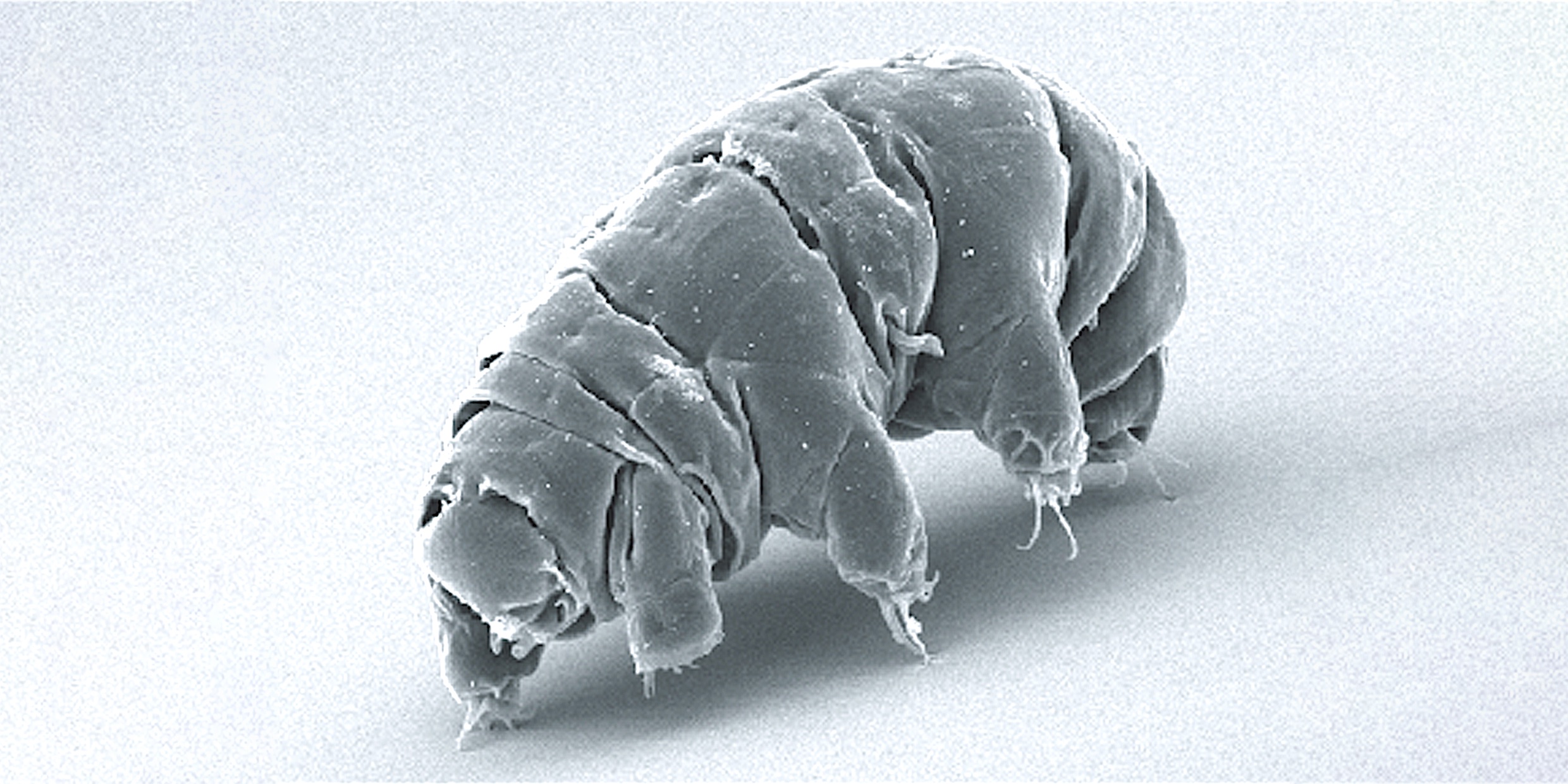

Tardigrades—literally, “slow walkers” — are sometimes called “water bears” because of the way they lumber along bearlike on eight stumpy appendages, or even more charmingly, “moss piglets.” Under the microscope, they do indeed look remarkably like vertebrates of some sort, but they have no bony skeleton. They are invertebrates, related to insects, but so unique they have a phylum all of their own.

Tardigrades do not interest scientists just because they are cute. They are also among the hardiest of multi-celled animals, maybe the toughest little critters of all. Dry them out and they go into a state of suspended animation in which they can live for — well, no one knows. When some apparently-lifeless, 120-year-old moss from an Italian museum was moistened, tardigrades rose as if from the dead and scampered about.

They can be frozen at temperatures near absolute zero, heated to 150 degrees centigrade, subjected to high vacuum or to pressure greater than that of the deepest ocean, and zapped with deadly radiation. It is not impossible that tardigrades could survive space travel without a spaceship.

Some scientists are trying to learn the tardigrade’s secret of surviving cold in order to keep frozen human organs fresh and viable for transplants.

My own curiosity, I confess, was based entirely on the tardigrade’s reputation as a water bear or moss piglet. I mean, who can resist a creature the size of a dust-mote that looks like something out of Beatrix Potter.

Scale is the secret of the tardigrade’s charm. It looks like it should be much bigger than it is, by about four orders of magnitude. It looks like a beast you might meet wallowing on a farm or tipping over trash cans in a national park. But you will more likely find them — if you have a magnifier — in wet moss in the gutters of your house.

For an hour, I observed my tardigrades scampering among strands of algae in a petri dish of water. They curled, stretched, crept and reached, presumably grazing, although I never saw them feed, which they do by sucking juices out of microscopic prey.

Watching them, I became more conscious than ever of just how much we are prisoners of scale. Another whole universe exists down there on the microscopic scale, and below. Electron-microscope images of tardigrades show every pore and bristle, the little hook-shaped appendages that pass for toes, and long wavy “hairs” that look wildly unkempt.

It would be fun if we could shrink ourselves like Alice and frolic with the tardigrades. Then shrink further and swim with the ciliates and rotifers that buzzed about my tardigrades like bees, and further still to observe the amoebic creatures too small to see with my microscope.

But why stop with the smallest creatures? Keep shrinking, down to the level of molecules and atoms, and observe those misty clouds of electric charge that are the building blocks of the universe — God’s Tinker Toys.

Even these are not the bottom floor. Smaller than the atoms are the quarks, elusive subatomic particles that hold themselves together in two’s and three’s so tightly that, so far, scientists haven’t been able to pry them apart. We describe tardigrades with familiar metaphors — water bears or moss piglets — but quarks are so far beyond the scale of ordinary experience that all metaphors fail.

And many physicists believe that even quarks are not the ground floor of reality. They are searching for things called “strings,” “quantum loops,” or “spin foam” that exist on a scale 20 orders of magnitude smaller than the nucleus of an atom, at a level of reality where even space and time break up into their smallest, indivisible units.

As I peered into my microscope, I was thinking of this almost unimaginable shadow world on a scale a 10 thousand billion billion billion times smaller than my water bears, that in its exotic shimmerings gives rise to the spectacular world of our senses.