Originally published 8 July 1996

Most people who make a living communicating science spend long hours reading the scientific literature. In a typical week, I peruse several books and a dozen journals.

It’s not always fun. Scientific literature — scientists talking to scientists — is dull by design. It’s like Joe Friday: “Just the facts, M’am.”

For example, I’ve been reading a series of reports in a [1996] issue of Science on the Galileo probe that parachuted into Jupiter’s atmosphere on December 7, 1995.

Twenty-four pages of tough slogging. Tables of entry parameters. Doppler measurements of wind velocities. Pressure and temperature measurements. Mass spectrometer measurements of atmosphere composition. Refractive indices. Solar and thermal radiation. Atmospheric scattering. High energy charged particles. Radio frequency signals.

Numbers, graphs, tables, formulas, diagrams.

A sample sentence (I advise you to skip it): “A complete calculation of the He mole fraction qHe needs to take into account quantitatively (i) the pressures of the sample gas Ps and the reference gases Pr (or instead of the latter, the pressure difference between the sample and reference gases) at the start (i) and end (e) of the measurement in the jovian atmosphere; (ii) the absolute temperatures of the same gas Ts and the reference gas Tr at the start (i) and end (e) of the measurements; (iii) the Lorentz-Lorenz function that connects the refractive index n of a nonpolar gas with its mass density p; (iv) the non-ideal gas characteristics of H2, He, Ar, and Ne as described by their compressibilities Z and virial coefficients B(T); and (v) the effects of an absorber in front of the SGC, which eliminates the traces of jovian methane from the measured gas sample.”

This apparent gobbledygook has a purpose.

Scientific literature emphasizes that part of our experience which is common to anyone who makes the observations in the same way. Good science shouldn’t depend upon the politics, gender, race, nationality, or emotional state of the observer, which is why none of these things is included in scientific reporting.

The dreary quantitative prose of science is a way of striving for objectivity. Ordinary language is often laden with cultural and personal baggage.

This struggle for objectivity, at the expense of easy-going fun, is what makes science a source of reliable knowledge.

Yet, it is not enough. We are emotional creatures. We have appetites. We are driven by awe, terror, love, hate. A diet of purely objective knowledge is oppressive.

Some lines from a poem of Mary Oliver:

Still, what I want in my life is to be willing to be dazzled--- to cast aside the weight of facts and maybe even to float a little above this difficult world. I want to believe I am looking into the white fire of a great mystery.

Mary Oliver asks to be dazzled, asks for more than the weight of facts, but she does not denigrate facts. Her poetry is filled with precise observations of the natural world, which match in their exactitude those of any scientist. Her exact knowledge of the world is the springboard from which she dives into the white fire.

The same white fire burns in those 24 fact-filled pages of data and analysis from the Galileo Jupiter Probe — if we are willing to see it.

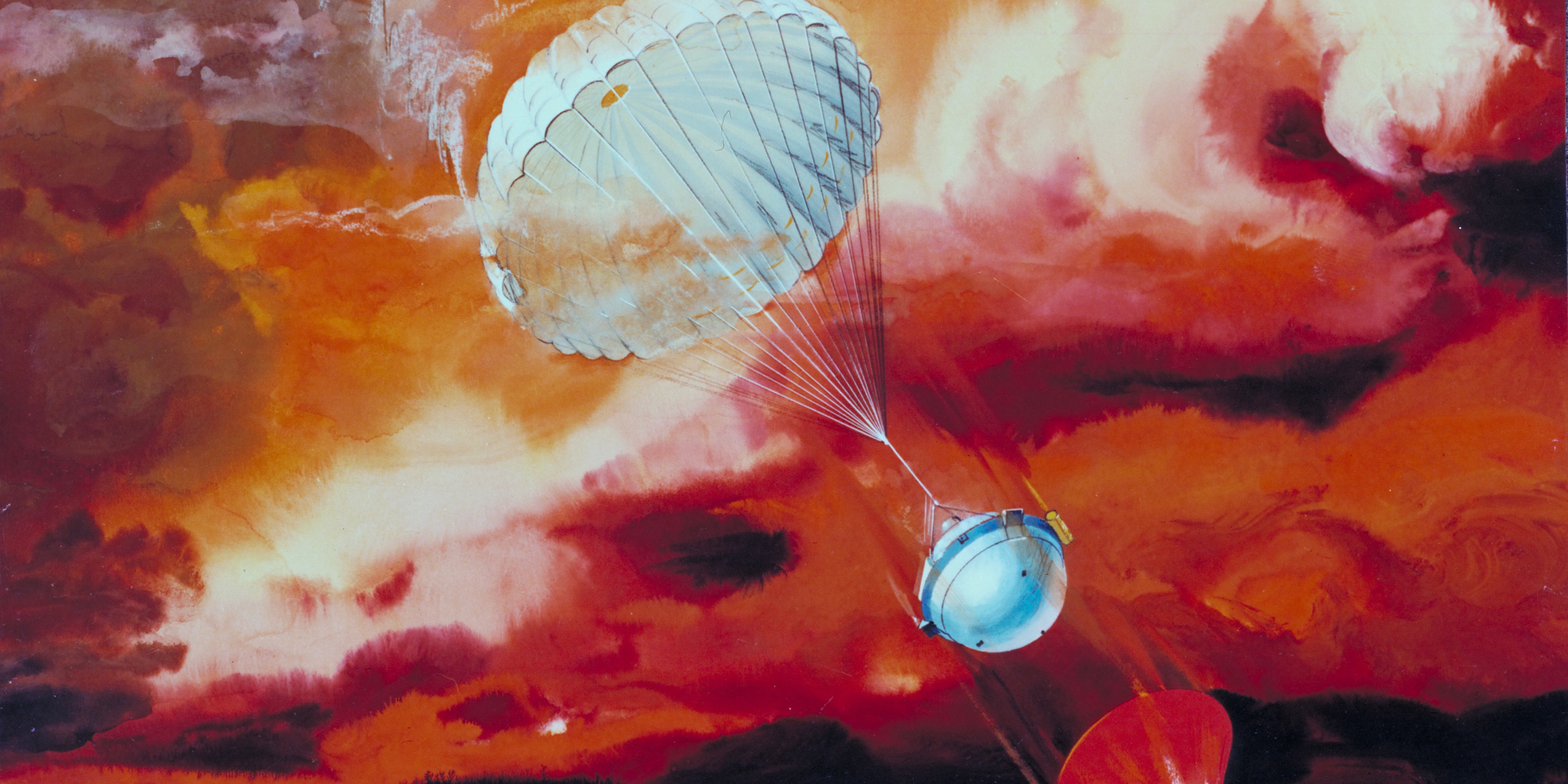

A spacecraft, named for a hero of human intellectual freedom, is hurled from our planet on a six-year voyage across the empty darkness, passing on its looping course Venus, Earth, the asteroid Gaspra, Earth again, and the asteroid Ida (discovering that Ida has a tiny moon), photographing the impact of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 as it smashed into Jupiter (an event hidden from observers on Earth), finally rendezvousing with Jupiter on schedule, more than half-a-billion miles from Earth, releasing a tiny human-built machine that fell into the giant planet, broadcasting a stream of data back to Earth as it plunged to oblivion.

Facts, yes, a flood of facts. But more. For a moment, we are allowed to float above our own difficult world, with Galileo’s dazzling images of blue-white Earth suspended in darkness, of pockmarked Gaspra, of Ida with its miniature companion, and of Jupiter — the giant planet, swirling with color, a maelstrom and forge of creation, the object of human consciousness extended into cosmic space and time — the white, white fire of a great mystery.