Originally published 9 January 1995

The spirit of adventure. The challenge of the unknown. Scientific curiosity. A common project to unite humankind. A high-tech alternative for scientists and engineers who have hitherto made their living producing the instruments of war. Entertainment. The inspiration of young people. A hedge on our survival in case the human race becomes extinct on Earth through self-annihilation or cosmic catastrophe.

Against all of this there is one reason for not going.

The cost.

It will take many tens of billions just to get started. An international investment that makes the cost of going to the moon look like loose change. Trillions over the next century.

That’s why no one with political savvy is talking about the imminent colonization of Mars.

However, if price were no object, it is perfectly reasonable to suppose that by the end of the 21st century, prospering self-supporting colonies might exist on Mars.

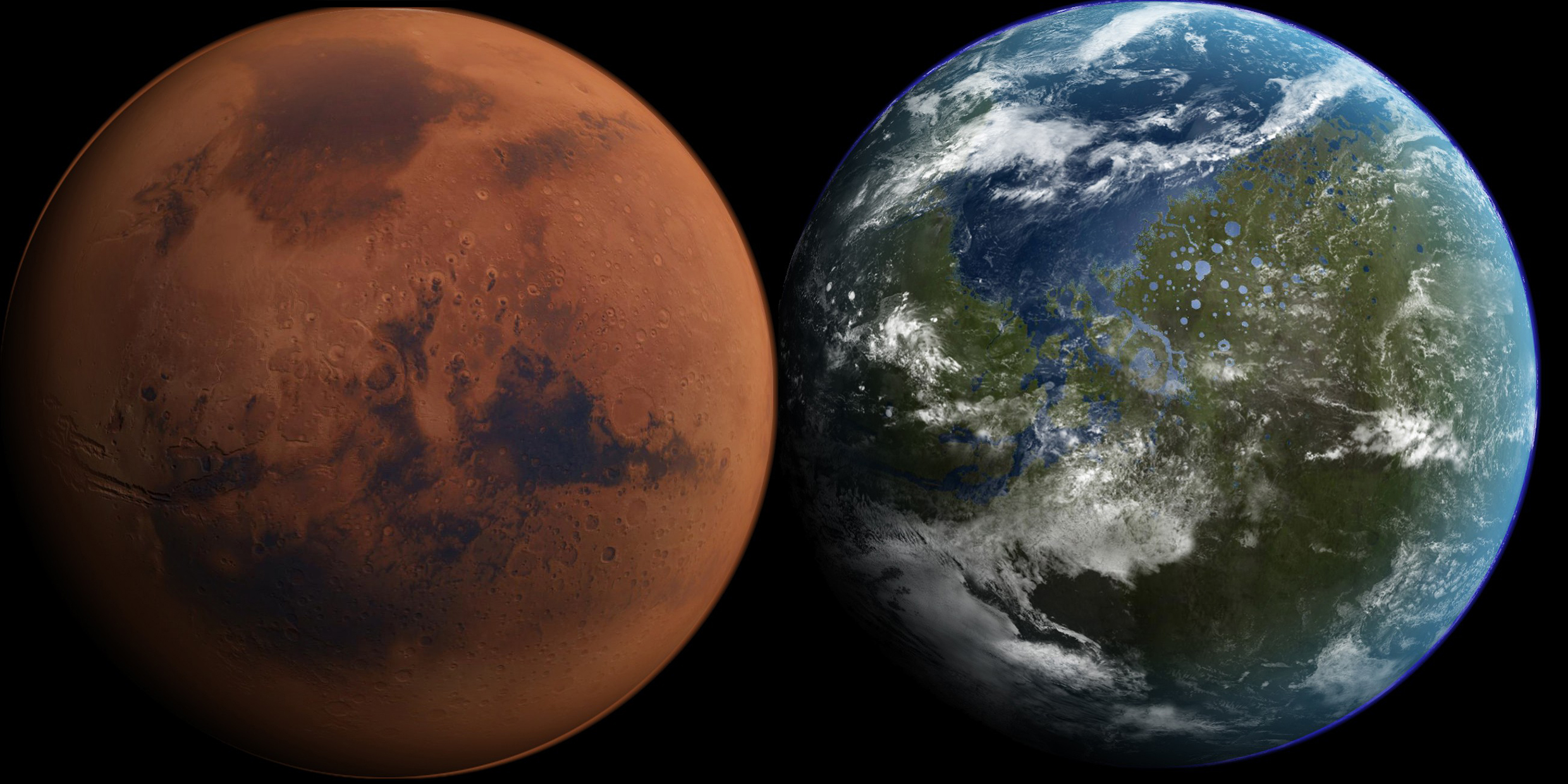

They will perhaps have modified the atmosphere to make it compatible with terrestrial flora and fauna, and have warmed the planet sufficiently so that subsurface frozen water will be flowing as liquid and falling as rain.

This transformation of the planet will probably involve bioengineered microbes, as the agents of change and sustainers of the new Martian biosphere.

The prospect is appealing. But how to pay for it?

With tongue only half in cheek, let me suggest that we take a page from the opening of the American west.

To encourage the building of transcontinental railroads, federal and state governments gave away huge tracts of land. Six square miles of land was typically granted to the railroad companies for every miles of track that was laid.

The companies parlayed free land into big profits.

In the years 1850 to 1871, the federal government passed out more than 130 million acres, or more than the combined areas of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana.

It was not a foolish transaction. Before the coming of the railroads, the government could hardly give away the western lands. In the wake of the railroads, federal land became immensely valuable.

So here’s the deal. By a treaty involving all spacefaring nations of Earth, ownership of Mars will be claimed in the name of humanity, then sold to finance exploration and colonization of the red planet.

To be sure, this would be a very long term investment, but if the price were right, irresistible. The romance of owning land on Mars should appeal to a broad range of small-scale private investors. I would gladly sign up for a few acres for my progeny, though I would likely resist an equivalent tax to pay for space exploration.

Land thought to have substantial subsurface water or mineral resources will be auctioned to the highest bidders, most likely multinational investment consortiums. A stake in Martian exploration and development by big business will stiffen political resolve to get the job done quickly.

The surface of Mars is roughly 36 billion acres, approximately the same as the land area of Earth. If, say, a tenth of that were sold at an average of $10 per acre, a Martian exploration program could be well under way.

Of course, large tracts of land will be held in trust for future public parks. These will include such natural wonders as the Olympus Mons and Tharsis Montes volcano complex and the Coprates Chasma canyonlands. Also historic sites such as the landing places of the Viking 1 and 2 probes.

Broad areas of lowlands will be reserved for future seas.

As the adventure proceeds, more land will be offered for sale. As the first colonies are established — say by the year 2030 — property values will appreciate, especially near settlements. By law, any land transactions between private owners will be subject to a massive tax, the proceeds of which will be plowed back into colonization.

By the end of the 21st century, Martian colonies should be economically independent of the home planet.

Early in its history, Mars was warmer, wetter and had a denser atmosphere than it does today; except for the composition of the atmosphere, the planet was altogether more congenial for life. It can be made that way again, although it might turn out to be more practical to modify life to fit Martian conditions (by genetic engineering) than to optimize Mars to fit life as we know it.

In any case, I have my Martian acres all picked out. Near latitude 30 degrees south, longitude 280 degrees, on the rim of a vast circular depression called Hellas Planitia. This is one of the few lowlands in the mid-latitudes of the red planet’s southern hemisphere. I figure this will become one of the first artificial seas on Mars, when the climate has been warmed sufficiently that water can exist as a liquid.

If I’m calling it correctly, my great-great-great-great-grandchildren will be owners of enviable beachfront property.

Billionaire industrialist Elon Musk aspires to create a sustainable colony on Mars by the middle of the 21st century. ‑Ed.