Originally published 24 July 1989

After the publication in 1959 of C. P. Snow’s The Two Cultures, it became fashionable to look for ways in which science and the humanities are interrelated. Usually this took the form of, ah, say, rooting out references to Renaissance astronomy in the poems of John Donne or to the Second Law of Thermodynamics in the novels of Thomas Pynchon.

All such borrowings, it seems to me, are superficial. If John Updike writes delightful verse on such themes as neutrinos and planets, we can conclude that Updike is scientifically literate, but not that science and art are fundamentally related. At the level of artistic and scientific expression, the chasm between the two cultures is as wide as ever. If there is a unity at some deeper level, it will take an archeologist to reveal it.

Yet if we dig deep enough, we will discover that the roots of science and art draw upon the same nutrients in the soil. Some of those nutrients are undoubtedly supplied by the genes; others are the products of culture. The imagination, scientific or artistic, feeds on what it finds.

Maxwell and Blake

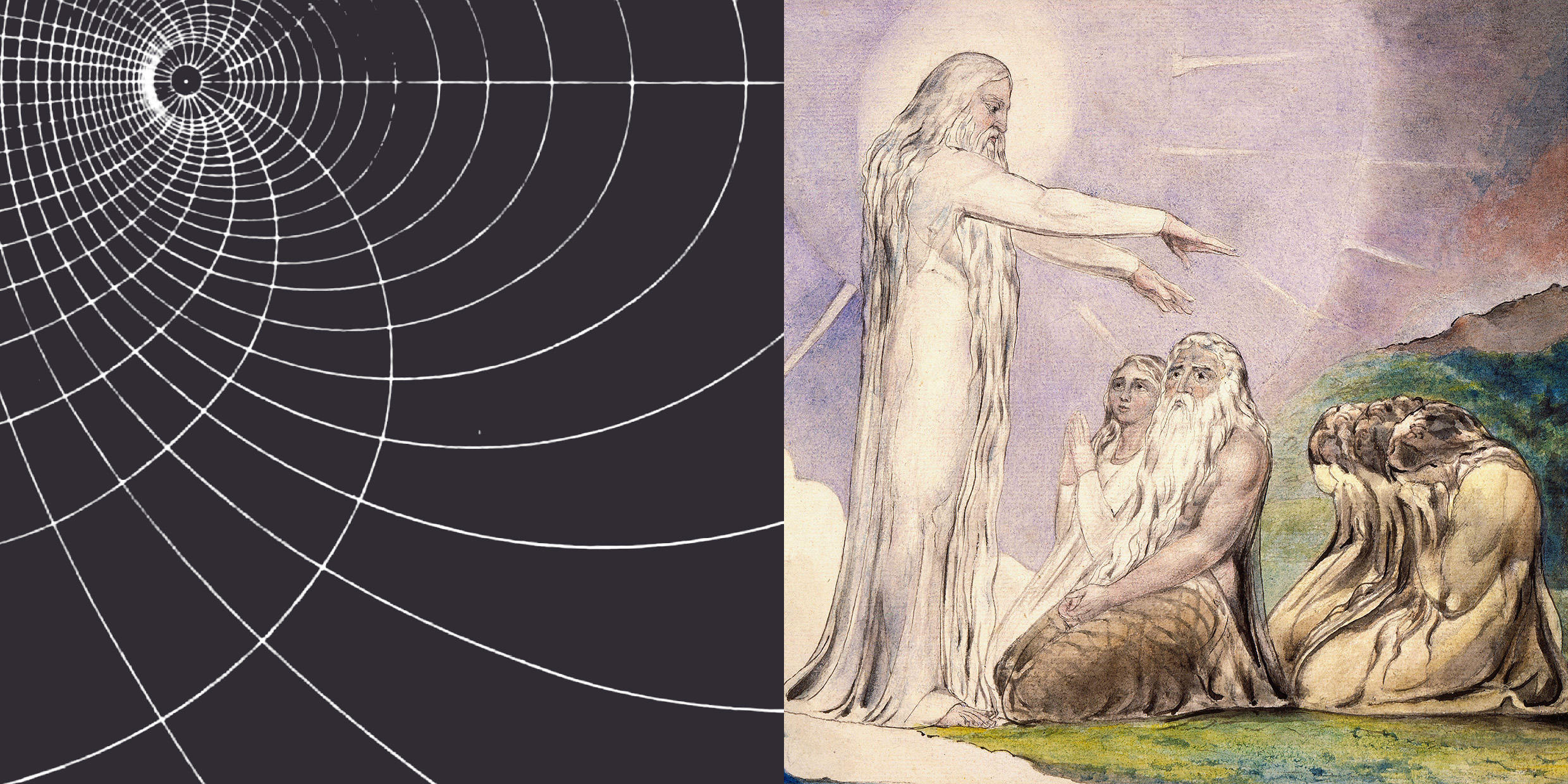

Pictured above is a 19th-century example of the deep unity of science and art, drawn from the electromagnetic field theory of James Clerk Maxwell and the art of William Blake. At first glance, the two would seem to have nothing in common. Blake railed against the science of his time, and Maxwell is hardly noted as a connoisseur of art.

Maxwell’s great work, the Treatise On Electricity and Magnetism, published in 1873, gave mathematical expression to the experimental research of Michael Faraday and united in one beautiful mathematical theory everything that was known about electricity, magnetism and light.

Chief among the ideas Maxwell took from Faraday is the “field,” a kind of tensioning of space caused by electricity. In Faraday’s brilliant intuition, the space around charged objects was resilient with possibility, like a stretched rubber sheet. This vibrancy of space was the field. You can’t see it, weigh it or touch it, but you can describe it mathematically and even draw pictures of it.

Included in Maxwell’s Treatise are drawings of fields around charged objects. When I first looked at these drawings, I had the uncanny feeling that I had seen them before, a sense of deja vu. And then I remembered: William Blake’s Book of Job.

I fetched Blake’s Job and was surprised to find that many of Maxwell’s field drawings matched, in vibrancy and form, one or another of Blake’s engravings.

Roots twisted together?

What does one make of this? Coincidence? A fluke of form, like finding a face in the clouds? Or is it possible that digging down one might discover that Maxwell’s electromagnetic fields and Blake’s powerful biblical images have roots that twist together? Could an archeologist of ideas excavate layers of accident and find the underlying unity?

Faraday invented the field while experimenting with wires, magnets and batteries during the very years when, in another part of London, Blake was engraving illustrations for Job. Faraday sprinkled iron filings near magnets and thought he saw in the swirling patterns of the iron grains an energy inherent in space itself. For the rest of his life, the problem of how force was transmitted between bodies of matter, and even through empty space, was his chief preoccupation.

Blake, too, was possessed by energy, force and motion. He tried desperately to give expression in his art to the invisible energy that surrounds bodies and is inseparable from them. Blake shared with Faraday a passion to try all experiments. The language of Faraday’s physics — spatial energy, lines of force, attraction and repulsion of contraries, symmetry and the breaking of symmetry — apply with equal aptness to Blake’s art.

An archeologist of ideas would trace the roots of Maxwell’s field drawings back through Faraday to Faraday’s mentor Humphry Davy to Davy’s friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge (and the idea of the universe as a “cosmic web”) to… Somewhere in the subterranean passages of Europe’s psyche, from which sprang Revolution and Romanticism, somewhere in the murky subconsciousness of the race, an archeologist following the thread of Maxwell’s thought would encounter Blake’s Tyger, burning bright in the forest of the night, physical force poised to spring, fearfully symmetric.

And surely one could do the same thing for the art and science of today. C.P Snow’s two cultures seem divided by a chasm only because our vision is horizontal. Somewhere deep in the interleaved strata of genes and culture, they come together, in a web of invisible capillaries feeding upon a common soil. Art and science are two fruits of the same tree.