Originally published 18 May 1987

There are as many stars in the Milky Way Galaxy as there are grains of salt in 10,000 boxes of salt. Our sun with its family of planets is a typical “grain.” With their largest telescopes astronomers can see more galaxies than there are boxes of salt in all of the supermarkets of the world, and among them the Milky Way is typical.

In that almost uncountable plurality of worlds — vastly more worlds than grains of salt in all the supermarkets of the world — are we alone? Is our sun the only star with a planet harboring intelligent life?

There is only one way of answering the question and that is to make the search for intelligent signals with optical and radio telescopes. Such a search does not come cheap. How vigorously we pursue the search — as a society — will depend upon what we expect to find.

Is there anyone out there?

Like many scientists, I am inclined to believe that the universe is filled with life — both more and less advanced than ourselves. Yet there is not a shred of scientifically acceptable evidence that life exists anywhere in the universe but here. Then why am I so confident that we are not alone? The answer is philosophical, not scientific. But the philosophical principle is based upon science.

Astronomers Sebastian von Hoerner and Carl Sagan call it the Principle of Mediocrity. The principle can be stated something like this: The view from here is about the same as the view from anywhere else. Or to put it another way: Our star, our planet, the life on it, and even our own intelligence, are completely mediocre.

I’ll grant you that the Principle of Mediocrity is not easy to accept. It runs counter the natural human tendency to think of ourselves as special. Indeed, it runs counter to what we have believed about ourselves throughout most of human history.

In the Western tradition it has been generally held that the universe was created by God specifically as a domicile for humans. Even today some scientists accept a related view, called the Anthropic Principle (anthrop, “man”), that says it is our existence that determines the nature of the universe we live in. According to this view, the universe must be precisely the sort of universe that will give rise to human intelligence — or else we wouldn’t be here to observe it. The Principle of Mediocrity, in its strongest form, denies any special role for humankind.

Nicholas Copernicus may have been the first to employ the Principle of Mediocrity when he displaced the Earth from the center of the universe and made it just one more planet circling the sun. Galileo was persecuted for denying that the Earth was the fixed center of the universe. Galileo’s contemporary Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake for, among other things, asserting our cosmic mediocrity.

Average in every way

The unalterable fact is this: Every time we thought that our physical place in the universe was special we discovered we were wrong. We thought that the village was the center of the universe, and we were wrong. We thought Rome or Jerusalem was the center, and that turned out to be wrong. We thought that the Earth was central, until Copernicus and Galileo convinced us it was just another planet. Then the sun turned out to be a typical star, in a typical neighborhood of the Milky Way Galaxy. And the Galaxy itself is only one galaxy among billions we can see with our telescopes.

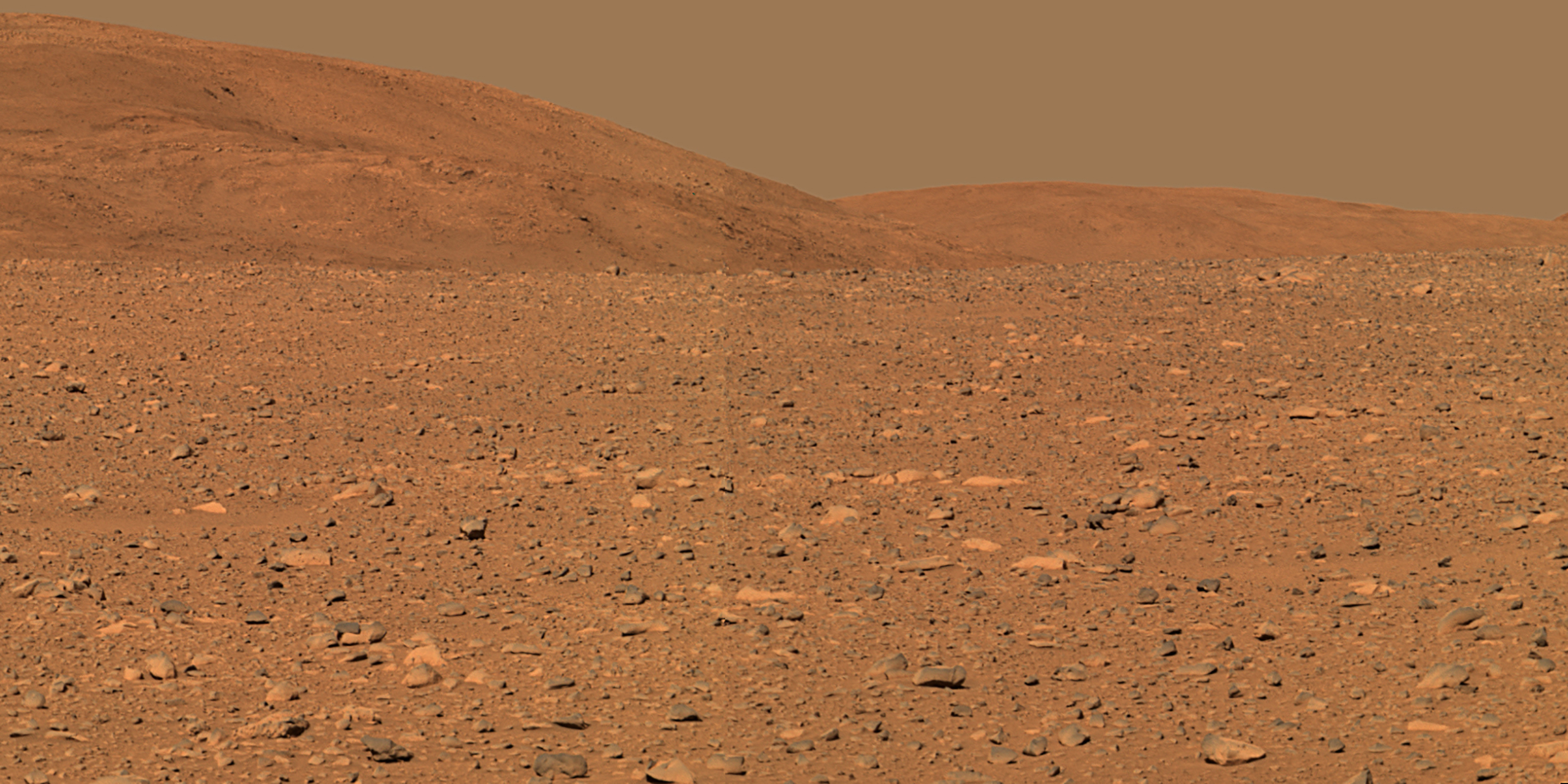

And there is more. Moon rocks are just like Earth rocks. Photographs of the surface of Mars made by the Viking landers, and of the surface of Venus by the Soviet Venera craft, could as well have been taken in Nevada. There are volcanoes and ice on the moons of Jupiter no different from on Earth. Meteorites contain some of the same organic compounds that are the basis for terrestrial life. Gas clouds in the space between the stars are composed of precisely the same atoms and molecules that we find in our own backyard. The most distant galaxies betray in their spectra the presence of familiar elements.

Indeed, the entire history of science is an argument for the Principle of Mediocrity. Not a proof, mind you, but a persuading experience. The Principle of Mediocrity is recurring disappointment raised to the status of a truth. And the Principle of Mediocrity says that we are not alone.

What is the alternative? If the sun is the only star with a planet inhabited by intelligent beings, then our star is the most remarkable star in the universe; it is the one grain of salt in all of the boxes of salt in the world that is utterly unique. At the very least, experience should warn us against that conclusion.

There are serious thinkers, including astronomers, who reject the Principle of Mediocrity as applied to extraterrestrial intelligence. They argue that if we are not alone — and if we are average — then there must be intelligent civilizations in the Galaxy far in advance of ourselves. Such civilizations would have modified the galactic environment to such an extent that their presence should be easy to detect. And if we haven’t seen them, the argument goes, then they are not there.

This last argument has merit, but in my view it is not sufficient to dissuade me of our cosmic mediocrity. Experience is a compelling teacher.