Originally published 11 May 1987

Thoreau, Emerson, and Hawthorne all record in their journals a moment when the shrill whistle of the Fitchburg Railroad intruded upon the tranquility of the Concord woods. The track of that railroad passed very close to Walden Pond, and Thoreau especially took note of the way the smoke-belching locomotive disrupted his country reveries.

Meanwhile, nearby, American entrepreneurs were building yet more railroads and canals, water mills and factories, and ingenious machines for weaving cloth and forging iron. Even as Thoreau hoed his bean field, the Industrial Revolution was under way, and by the end of the 19th century Americans had made themselves the internationally-acknowledged masters of machines.

The writers of Concord and the mill-masters of Pawtucket and Lowell are two sides of the American character. Since our beginning as a nation, we have had a love/hate relationship with machines. We have unabashedly flung a web of machinery across the land (and into space), and at the same time we long nostalgically for a simple life in the unspoiled wilderness.

Perhaps it is our ambivalence toward machines that makes us find so much to admire in the Renaissance genius Leonardo da Vinci. Of the artists and scientists of the past, he is the best known and most revered. His ingenious mechanical inventions were centuries ahead of his time. His paintings—The Last Supper, the Mona Lisa—suggest peace and beauty. In Leonardo’s work (we like to imagine), the lion of technology laid down peaceably with the lamb of art.

A look at Leonardo

This past week [in May 1987], an exhibition of Leonardo’s mechanical inventions opened at the Boston Museum of Science. Twenty-four large working models, based on drawings in Leonardo’s notebooks, are on display. They are fashioned of wood, brass, and fabric, and include a clock, a flying machine, a helicopter, a parachute, a paddle-wheel ship, various mechanical mechanisms, instruments of war, power tools, and scientific instruments. Most of the models can be operated by museum visitors.

The exhibition is sponsored by IBM, which owns a large collection of Leonardo models. Selections from the IBM collection have been exhibited at various locations since 1951. They have always proven immensely popular.

The models at the Museum of Science are impressive evidence of Leonardo’s ingenuity. He saw in his mind’s eye and worked out on paper many mechanical ideas that would not come to fruition until our own time. He anticipated manned flight, machine tools, the mass production of goods, and many other aspects of contemporary technological civilization.

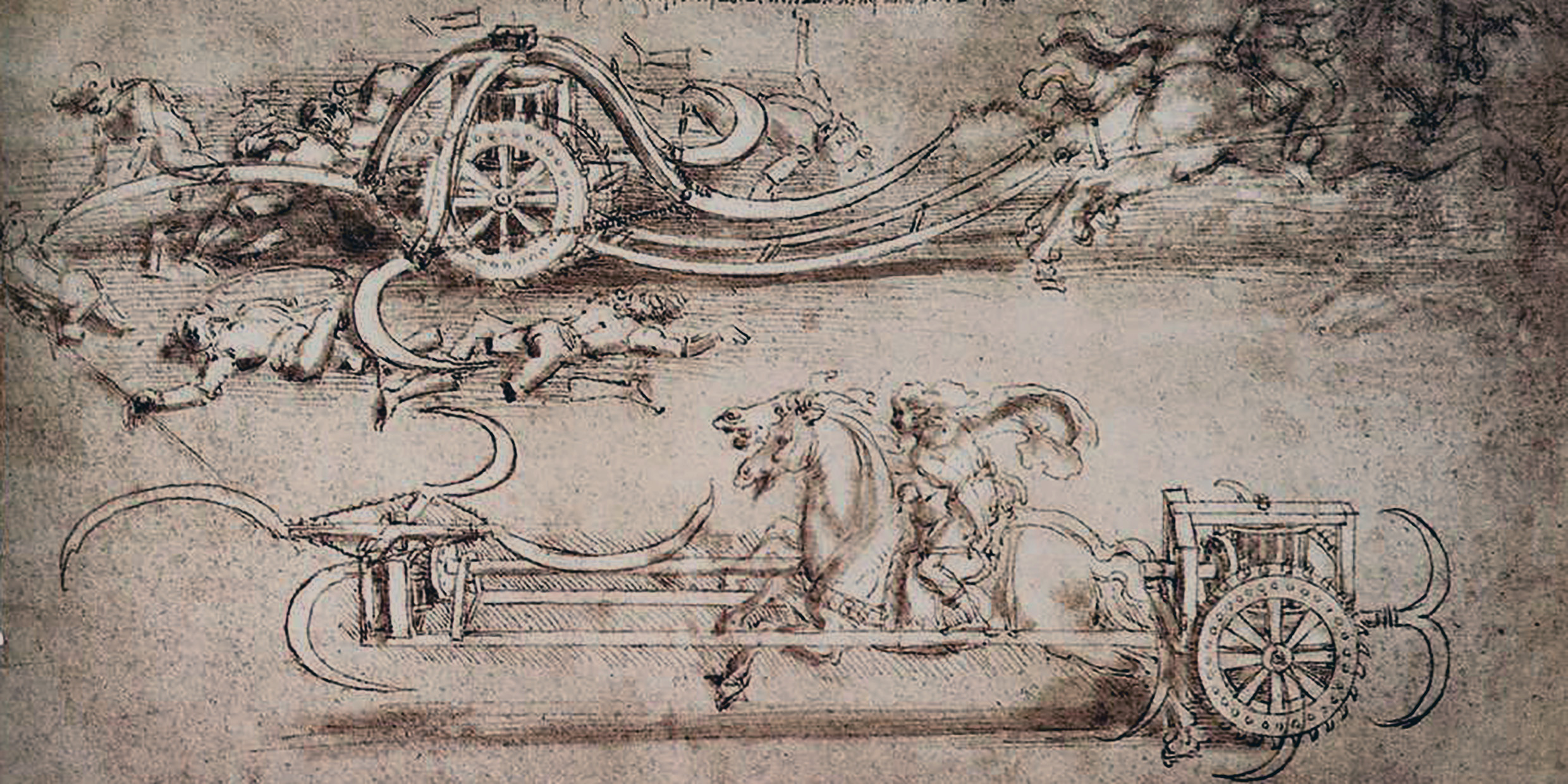

The models in the museum show are the complement of the Mona Lisa. Leonardo could sketch the face of a child or a wildflower with wonderful delicacy. And in the mechanical models we see a man in love with machines. Even the machines of war — the scaling ladder, the gun carriage, and the tank — seem like harmless toys rather than weapons of terror. The machines and the Mona Lisa are the two sides of Leonardo as mythical hero: the “Renaissance man” who lives in harmony with both technology and nature.

The dark conflict

But there is another Leonardo, a hidden Leonardo who is seldom put on public display. For every graceful wildflower among Leonardo’s drawings there are sketches of violent storms, explosions, and turbulence. For every sweet-faced cherub there is the face of an old man distorted by anger or fear. For every madonna and child there are men and animals locked in mortal combat. And the weapons of war, as we see them in the notebooks, do not look like toys: We see drawings of spinning scythes surrounded by dismembered bodies, bombards raining fire, and shells exploding in deadly star-bursts of shrapnel.

Leonardo’s vision of nature and machines was not as harmonious as it is sometimes made to seem. Yes, he bought caged birds in the shops so that he might set them free. And, yes, among his technical sketches (and the museum models) are many machines designed to increase human well-being and alleviate drudgery. But Leonardo also saw a dark conflict between nature and technology that resisted resolution.

Leonardo wanted to learn from nature a more humane way of living, with machines as willing servants. But what he discovered in nature was not always pretty, and where his studies led him was not always a technological utopia. There is a grim and terrible underside to the creative genius of Leonardo. His experience offers little hope of resolving our own love/hate affair with machines.