Originally published 20 April 1987

One night in the winter of 1937, a young theoretical physicist at Iowa State University at Ames got into his car and drove at top speed along the dark highways of the prairie.

It was a way of relieving his weariness and depression. He had been thinking for some time about the possibility of finding an electronic method for solving complicated mathematical equations. His goals were clear, but for weeks he had made no progress toward achieving them. He was desperately unhappy.

The driving relaxed him. At some point during the night he crossed the Mississippi River into Illinois and pulled into a roadhouse. The place was quiet. He ordered a drink. As he sat alone in the tavern things began to click in his head. He thought of a way to store numbers electrically, using capacitors (devices that store a quantity of electric charge). He thought of a way to keep the electrical memory fresh by periodic jogging. And he thought of a way to combine bits of information electrically so as to perform certain logical operations.

He knew he had found a way, in principle at least, to build a very powerful machine for doing computations electrically. He got into his car and drove slowly home.

The physicist was John Vincent Atanasoff, and that night in the Illinois roadhouse was an important one in the history of computers. Atanasoff has as good a claim as any to be considered the inventor of the electronic digital computer. In a telephone conversation last week, Atanasoff, now 83 [in 1987], affirmed his priority. “I’m the first man who did it,” he said, “there isn’t any question.”

First on three ideas

For something as complex as the modern computer, it is difficult to assign credit for invention to a single person. The computer is not so much a thing as a set of ideas, and it is notoriously difficult to pin down the origin of an idea. But there are some ideas that have been part of every modern computer, and among them are three that Atanasoff was the first to implement: 1) Using a binary system (no digits except 0 and 1) for representing numbers and data. 2) Doing all computations electronically, for speed, rather than using wheels and ratchets or mechanical switches. 3) Organizing the machine so that the computation circuits and the memory are separated.

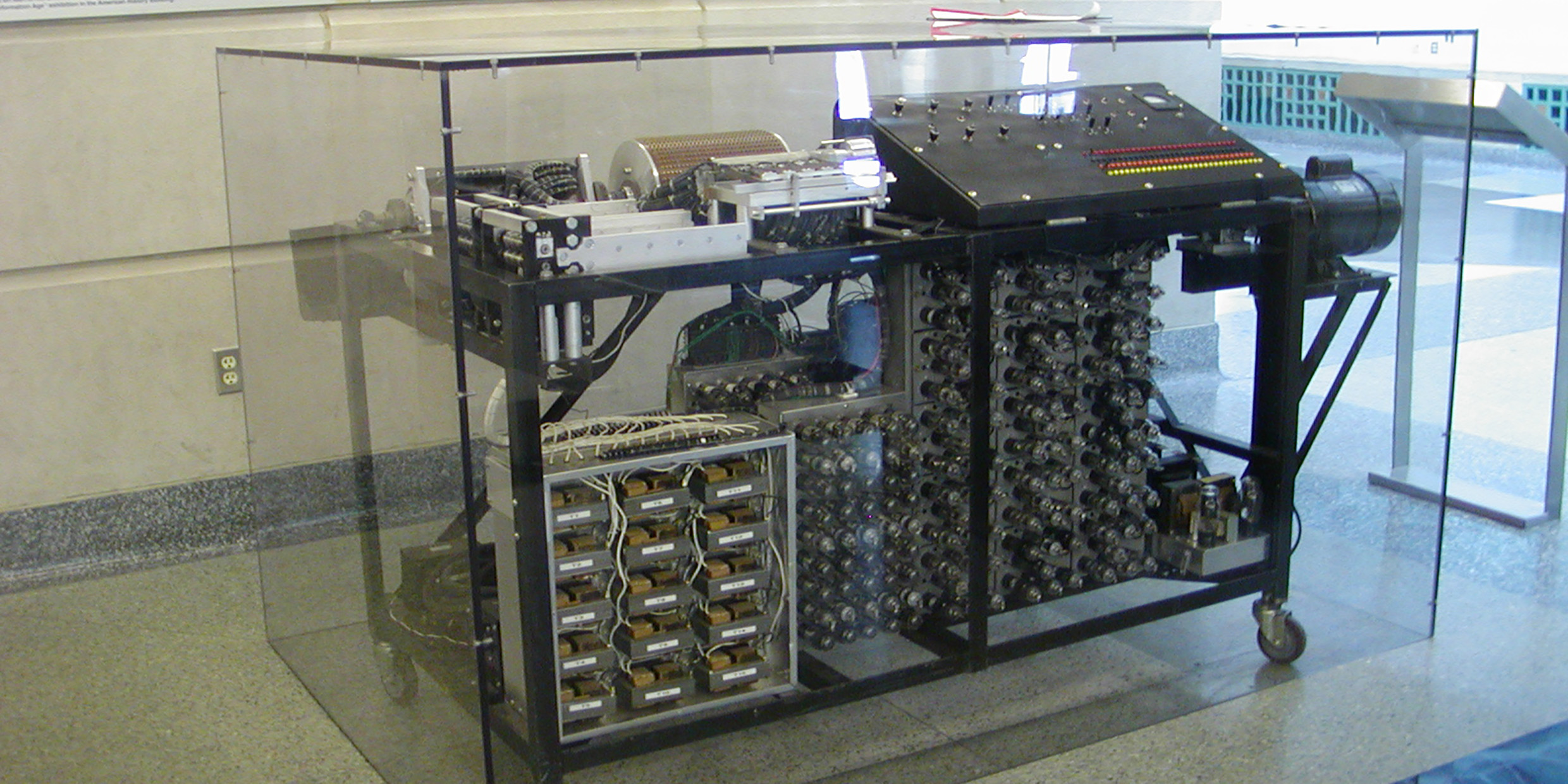

With his graduate-student assistant, Clifford Berry, Atanasoff between 1939 and 1942 constructed a working machine embodying these principles. The computer performed as expected, although problems were encountered with the use of punched cards for getting numbers into and out of the machine. The problems would very likely have been solved had World War II not interrupted the work. Atanasoff and Berry were not able to persuade the local draft board that an electronic computer could help the war effort. The two physicists turned to other war-related work, and their computer gathered dust in the basement of the physics department. Like most equipment abandoned in the basements of science buildings, it was cannibalized for parts — and so passed into oblivion.

Europeans often hear that the first electronic computer was the machine built in England in 1943 by Alan Turing and his colleagues to crack the German war code. Americans are usually told that the first electronic digital computer was the ENIAC machine built by John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering of the University of Pennsylvania, which became operational in 1945.

Although I have read a fair bit about the history of computers, only rarely have I come across Atanasoff’s name. For the facts of Atanasoff’s life and work I am indebted to an article by Allan Mackintosh in the March 1987 issue of Physics Today. Mackintosh unambiguously calls Atanasoff’s machine the first electronic computer, as do Arthur Burks and Alice Burks who have written a fine history of the ENIAC computer. John Mauchly, co-developer of the ENIAC, visited Atanasoff at Iowa State in 1941 and was apparently influenced by Atanasoff’s work. But, sadly, Atanasoff’s contribution to modern computers has been mostly forgotten.

Being ahead has its drawbacks

The first electronic digital computer was an idea whose time had come; several groups working more or less independently arrived at almost the same place at the same time. Atanasoff was simply a bit ahead of the pack. Being ahead had its costs. Atanasoff was required to work mostly on his own, in a place far removed from the mainstream of computer development. He had trouble finding anyone who recognized the significance of his work. Iowa State supported Atanasoff’s work, but none of the university officials fully appreciated what he was up to. The university failed to patent Atanasoff’s inventions, and that bit of bumbling would be later regretted. Most of all, being ahead of the pack meant that Atanasoff was that much easier to forget.

Atanasoff is unhappy that his work has been so often overlooked, and pleased with the recognition that is finally coming his way. Next month he will receive an honorary doctorate degree from his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin. The degree will be a fitting end to a story that began in 1913 when a 10-year old boy found among his mother’s books one that discussed number systems with different bases, including the base-two binary system. Atanasoff read the book and never forgot it. It was still in his mind when in 1933 he began to think seriously about computers.

Perhaps the most intriguing episode in the Atanasoff story is that long, crazy drive into the night that sparked the invention of his machine. Atanasoff had immersed himself in the problems he was trying to solve. His mind was undoubtedly working subconsciously to find solutions. The high-speed drive halfway across the state of Iowa was the trigger that let the ideas flow into consciousness — and into history.