Originally published 6 April 1987

A poet of Shakespeare’s time was apt to say that his love (for his lover) was not “sublunar.” He meant that his love was like the stars — constant and unchanging.

According to the philosophy that had prevailed since the time of the Greeks, change occurred only below the moon, in this “sublunar” world of jumbled elements and unconstant emotions. By contrast, the realm of the stars was immutable. The stars, like the poet’s love, were fixed and eternal.

And then, to the consternation of poets and philosophers, in the winter of 1572 a new star blazed out in the constellation Cassiopeia. The star was well-placed for viewing, high overhead in the evening sky. It was brighter than all other stars in the sky, bright enough to be seen in broad daylight. All Europe was agog.

But was this new star really above the moon, in which case the philosophers were wrong and the heavens do change? Or was the “star” in Cassiopeia not a star at all, but some sort of luminous object in the Earth’s own atmosphere? There was one man in Europe eminently suited to answer the question — the well-born, brash and gifted Dane, Tycho Brahe.

On the evening of Nov. 11, 1572, Tycho was walking home to supper when he happened to glance up at the stars above his head. He saw the new star at once, the nova stella. Afraid to believe his own senses, he asked servants and neighbors to look into the sky and describe what they saw. They confirmed his observation. The star was real.

Philosophers in error

Tycho was a talented astronomer, and had recently built a fine new instrument for determining the positions of stars. Carefully, he measured the distance of the new star from the stars of Cassiopeia. He continued these observations at different times of the night, and throughout the winter as the star slowly faded. And he collected positions of the star from other European observers. He was trying to determine the star’s parallax.

Parallax is the apparent change in the position of an object when viewed from two different places. To observe parallax, hold your finger in front of your nose and look at it first with one eye and then with the other. Notice how your finger seems to move against the background. Now extend you arm, moving your finger further away, and note how the parallax lessens. The object in Cassiopeia did not move at all against the background of the stars when viewed from different positions. From this observation Tycho could readily calculate that the new star was situated in the highest heaven, far beyond the moon. The philosophers were wrong; the heavens do change.

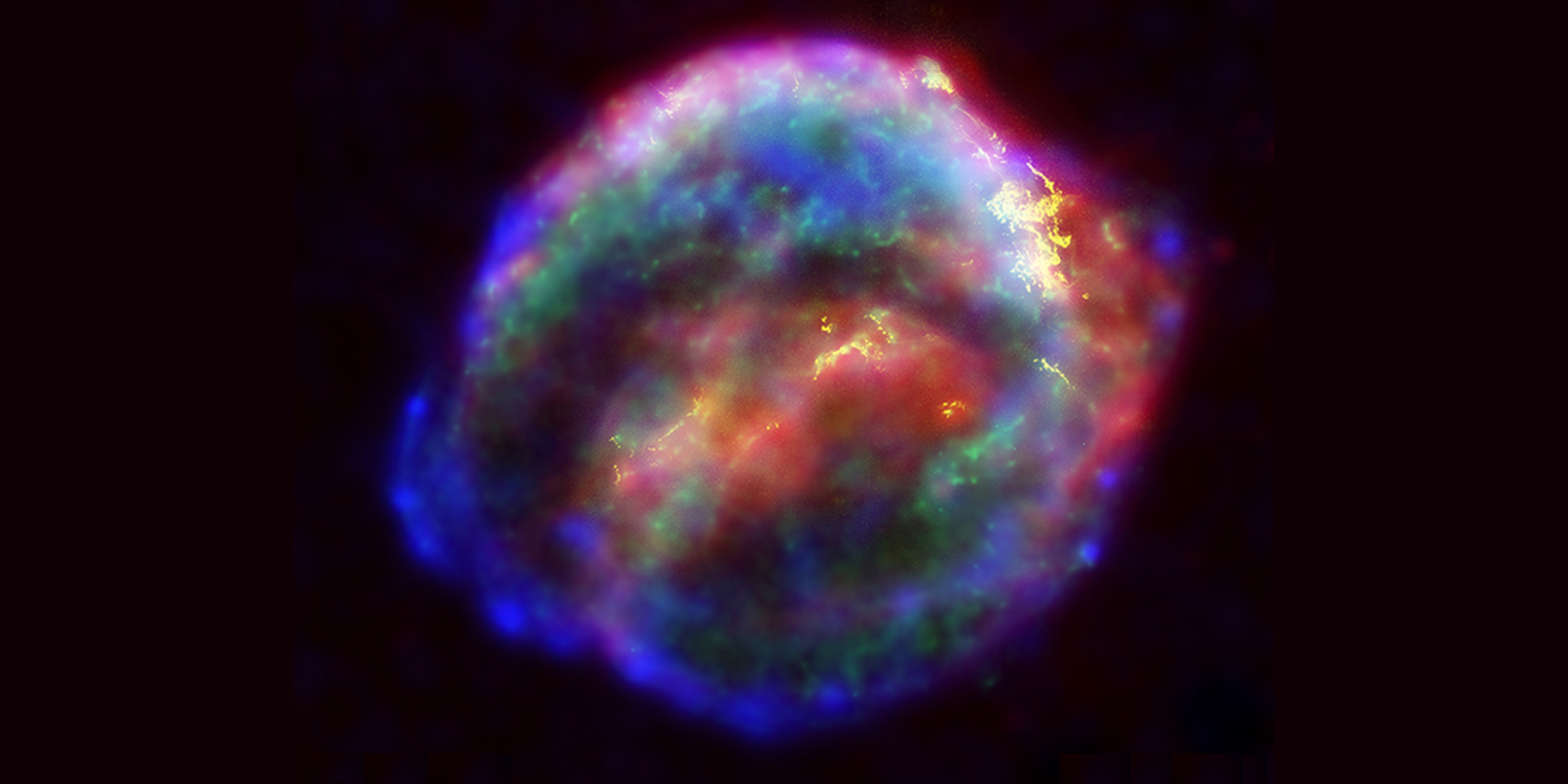

We now know that the new star of 1572 was a supernova, the catastrophic explosion of a star too far away to have been visible before the detonation. The supernova of 1572 occurred at a crucial time in the history of astronomy. Thirty years earlier Copernicus had boldly suggested that the sun, not the Earth, was the center of the universe. Forty years later Galileo, with the aid of the first astronomical telescope, would force a reluctant world to concede that Copernicus was right. The supernova of 1572 changed the supposedly unchangeable sky, and helped tip the scales in favor of a brave new world.

And if one supernova was not enough, in 1604 another brilliant star appeared in the constellation Ophiuchus, only a few degrees away from a rare conjunction of the planets Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. That a new star should join an already remarkable gathering of planets was ominous. The star in Ophiuchus was on everyone’s lips: Did it foretell the overthrow of the Turkish empire? A new European monarch? The Day of Judgment?

Once more, the heavens change

On Oct. 10 the new star was brought to the attention of Johannes Kepler, Mathematician to the Emperor Rudolph in Prague. If Tycho Brahe was the greatest observational astronomer of his time, Kepler was the greatest theoretical astronomer. He followed the rise and decline in the brightness of the star over many months, and collected data from other observers. He conclusively demonstrated the absence of parallax, and therefore the celestial distance of the star. Once again, the “immutable” heavens of the philosophers had changed.

Both Tycho and Kepler published books on the new stars, adding to the growing debate on the true arrangement of the universe. A few years later Galileo turned his telescope upon the heavens and discovered things that no bookish philosopher had dreamed of — spots on the sun, craters on the moon, the satellites of Jupiter, the rings of Saturn, the phases of Venus, and stars apparently without number. Modern astronomy was born.

Before 1572, no bright supernova had appeared in Earth’s sky for 400 years. The supernova of 1604 would be the last until February of 1987. In the 32 years that separated the two new stars of the Renaissance, the universe above the moon (and below it) was changed forever.