Originally published 12 December 2004

It is the morning of July 5, 1054 A.D. You wake to a thin crescent moon between the horns of Taurus the Bull, low in the eastern sky. And nearby — wonder of wonders — a brilliant new celestial object, apparently a star, but shining more brightly than any star you have ever seen, four times brighter than Venus, so bright that for the next several weeks it will be visible even in daylight.

The new star slowly fades. Within a few years it is gone.

The new star of 1054 was visible from pretty nearly every inhabited part of the globe. Chinese observers recorded it. Japanese and Arabs too. It is hard to imagine that anyone able to rise from their bed might have missed it.

We now know that the blazing light in the sky was a supernova — the explosive death of a massive star too far away to have been previously visible to the unaided eye — one of only a dozen or so of these rare celestial events that were recorded by human observers before the advent of telescopes.

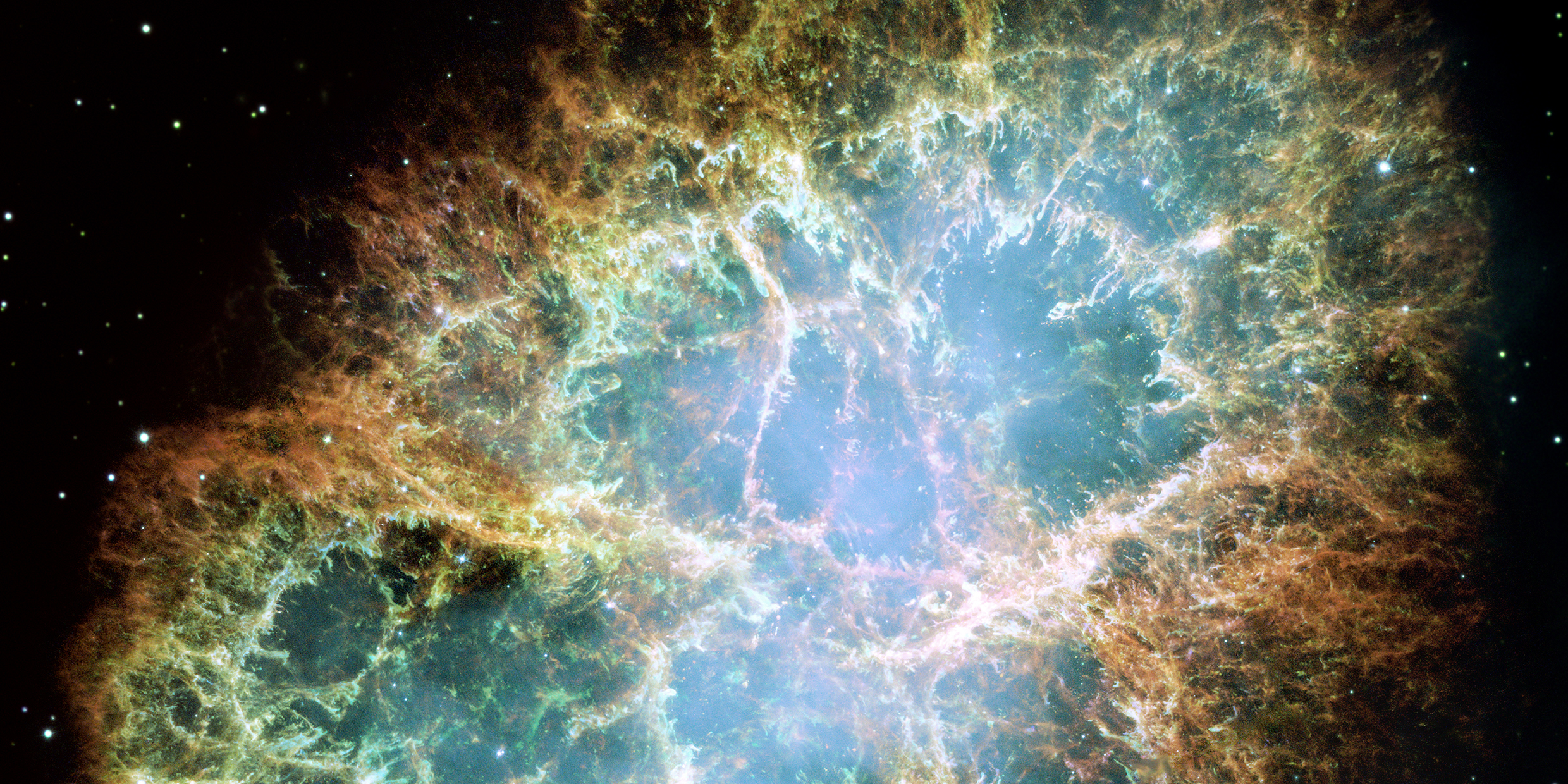

Today, if we turn our telescopes to the place between the Bull’s horns where the new star appeared, we see the shattered remnants of the progenitor star, still racing outwards, called (from its shape) the Crab Nebula.

It has always been something of a mystery why no European records of the supernova have been found. Surely so spectacular an event must have attracted wide notice, especially among a people obsessed with religious superstition. It was, after all, not so many years after the turn of the millennium, when many Christians expected the end of the world.

It turns out that the supernova may have a European record after all. I thank Gerry Wrixon, president of Ireland’s University College Cork — and a radio astronomer — for drawing my attention to an article published in 1997 in Peritia, the journal of the Medieval Academy of Ireland.

Daniel McCarthy, a computer scientist, and Aidan Breen, a scholar of Celtic studies surveyed Irish monastic records from the coming of Christianity in the 5th century to the dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century, compiling an inventory of astronomical and meteorological observations.

They found nearly 100 relevant notations, including observations of eclipses, comets, and extraordinary auroral displays. Two entries record clouds of dust (from Icelandic volcanos) that colored and obscured the sky. An annal entry in the year 1054 is interpreted by McCarthy and Breen as a record of the supernova.

The pertinent 1054 entry states: “A round tower of fire was seen in the air over Ros Ela on Sunday the feast of S. George for five hours of the day.”

It takes a stretch of the imagination to connect this short passage with a supernova. The relevant part, according to McCarthy and Breen, is that something fiery was seen from a certain identifiable place for five hours in daylight.

Ros Ela is a townland near the ancient monastic site of Durrow, in County Westmeath, and the supernova would indeed have appeared over that place as observed from the monastery.

As for the “round tower of fire” and the spurious date (the feast of St. George is April 24), these appear to be later interpolations into the record for the sake of connecting the celestial event to the Coming of the Antichrist as predicted by Revelation.

The “tower of fire” presumably represents the scriptural “great star…blazing like a torch” (Revelation 8:10), and St. George would have been a logical warrior hero to confront the demon horde. The fanciful passage that follows the presumed reference to the supernova evokes an apocalyptic vision.

Slight evidence, indeed. But the Irish annalists proved themselves to be observant and generally accurate with their recordings of eclipses and comets, most of which can be checked using modern astronomical computation. It would have been puzzling if they failed to note what must have been the most spectacular apparition of all.

For the monks of 11th-century Ireland, these extraordinary celestial events were interesting primarily as apocalyptic signs and portents to be interpreted within a scriptural context.

Anticipation of the End Times has been a perennial preoccupation of certain superstitious Christians — no less today than in the Middle Ages, as witnessed by the hugely popular Left Behind series of novels. Nature will never fail to provide omens and portents to a mind predisposed to believe.