Originally published 6 May 2003

Has there ever been a more astute observer of the war between the sexes than James Thurber?

With wry words and acerbic pen, Thurber chronicled the irreconcilable interests of men and women in essays and cartoons that appeared in The New Yorker during the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s. Women may deny that Thurber was an objective observer, but males of my generation are pretty much convinced that he got it right.

And, as we shall see, science backs him up.

One famous sequence of Thurber cartoons is called “The War Between Men and Women.” The conflict starts with a man tossing a drink into the face of a woman (we do not know with what provocation). High points of the story come with the “Capture of Three Physics Professors” by a smirking, gun-toting lady, and the “Surrender of Three Blondes” to a trio of bewildered, bow-tied gentlemen.

Thurber’s females are generally larger and more assertive than the males, who are often depicted as timid, mustachioed milquetoasts. At the end of Thurber’s war, however, men come out on top. A scowling female commander hands over the symbolic baseball bat to her bemused male counterpart.

All of this comes to mind because I have recently read two books about human chromosomes — Matt Ridley’s Genome: The Autobiography of a Species in 23 Chapters, and David Bainbridge’s The X in Sex: How the X Chromosome Controls Our Lives.

Among the chromosomes, none are more interesting than the X and Y, the driving agents of sex.

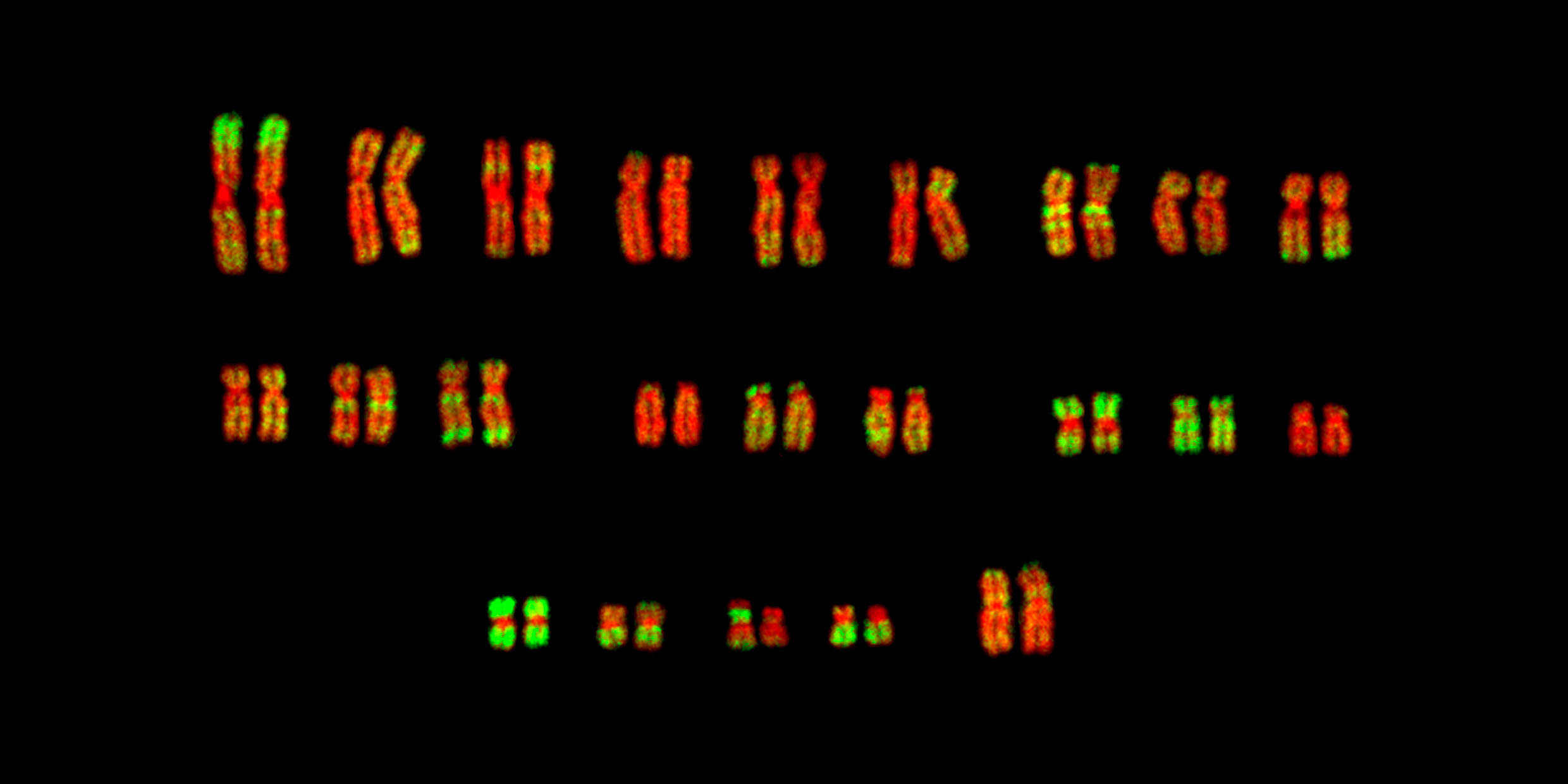

The human genome — our complete set of genes — comes packaged in 23 pairs of chromosomes. The members of each pair are identical, except for the X and Y. The X is average in size for a chromosome. The Y is a shriveled little thing, smaller than any other chromosome.

The cells in a woman’s body contain two Xs. The cells in a man’s body contain an X and a Y — and thus are we divided into sexes. A woman always contributes an X to an embryo; a man can contribute an X or a Y, depending on which sperm wins the race to the egg.

Crucially, the Y bears a gene called SRY, from “sex-determining region on the Y chromosome.” The SRY gene makes a protein that switches on the SOX‑9 gene, which switches on the MIS gene. It appears that MIS makes testicles in a developing embryo, and testicles make boys by releasing hormones.

No Y, an embryo becomes a girl. A Y highjacks the process and makes a boy.

It turns out that Thurber’s view of the war between men and women reproduces itself at the level of the chromosomes, as the diminutive but scrappy Y engages the larger and overbearing X in eternal evolutionary strife. In fact, Ridley calls his chapter on the X and Y chromosomes “Conflict.”

It appears that the X and Y originally evolved from a matching pair of non-sex chromosomes. But once they got involved in sex determination, all hell broke loose. As Ridley puts it, “The two chromosomes no longer have each other’s interests at heart.”

Remember that X chromosomes spend two-thirds of their time in females and only one-third in males. “Therefore,” Ridley states, “the X chromosome is three times as likely to evolve the ability to take pot shots at the Y as the Y is to evolve the ability to take pot shots at the X.” The result is that the Y has been reduced to a stump of a thing, although bearing the all-important SRY gene.

Meanwhile the X has some important genes, too, including DAX1, which Bainbridge rather testily calls the “anti-testicle” gene. Ordinarily, the SRY gene defeats DAX1 and makes a boy, but in rare cases where a human X chromosome has two copies of DAX1, the embryo develops into a normal female, although such people are genetically male.

Enough! You get the point. The war between the sexes has been going on genetically for millions of years, and it can hardly be surprising that there is so much tension at the level of the organism.

After all, we are creatures of our genes, and genes have no one’s interest at heart other than their own.