Originally published 18 March 2003

Every stargazer with a telescope has been looking at Saturn lately. This year the planet reaches the point in its orbit that brings it closest to the Earth. It appears bigger and brighter than at any time in the past 30 years.

But that’s not the half of it. It’s Saturn’s ring that makes the planet such a marvelous sight in a telescope, and this year the ring is ideally oriented for viewing.

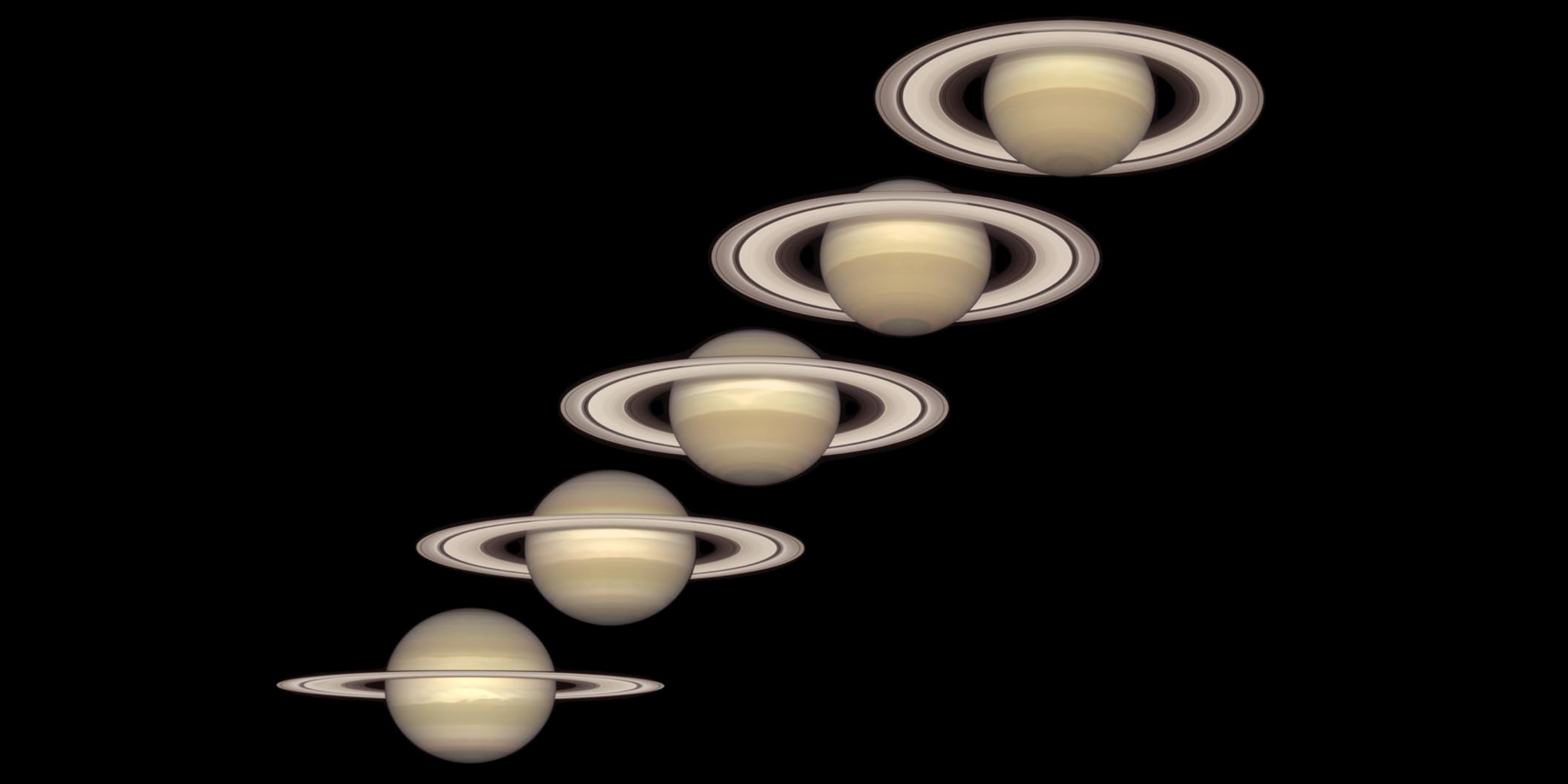

Think of the ring as the thin flat brim of a hat on a man’s head, and imagine, too, that the man has his head tipped forward, chin on chest. If you are standing in front of the man, or behind him, you will see the brim as a full ellipse. If you are standing off to one side or the other, you will see the brim as just a line.

Like Earth, Saturn’s axis is tilted to the plane of its orbit, and these days the tilt is maximally away from us. It’s like standing directly behind the man with the tipped hat. The ring is prominent as an open ellipse.

I’ve spent a good part of my life showing folks things through telescopes — planets, comets, stars, star clusters, nebulas, galaxies. Nothing so evokes gasps of delight as Saturn’s ring. The reason, I think, is a collision of the expected and the improbable.

A ringed sphere is the archetypal planet of our childhood, familiar from a thousand comic strips, coloring books, classroom poster boards, stickers, rubber stamps, birthday cards — you name it. So, when we see Saturn, there is a kind of instant recognition, like meeting a relative one knows only from the family photo album.

But there is also the shock of reality, a sense of “Oh, my God, it actually exists!”

When Galileo first saw Saturn’s ring through a telescope in July 1610, he had no basis for familiarity. Nothing in his experience could have prepared him for what is, after all, completely improbable. The planet’s ring was then tipped at a slight angle to the Earth. He saw what appeared to be blobs of light to either side of the planet and imagined that they were stationary attendant satellites of Saturn. He had already correctly deduced the nature of Jupiter’s moons, and was inclined to think that Saturn might have moons also.

When two years later he looked at Saturn again, the supposed satellites were gone. Of course, the ring was still there, but he was now seeing it edge-on and invisibly thin. His confidence was shaken. “Has Saturn devoured his own children?” he asked in amazement.

It wasn’t until 1659 that a Dutchman, Christian Huygens, finally understood what everyone had been puzzling at for almost half a century — a ring viewed from different orientations.

Even then astronomers were baffled as to the nature of the ring. Was it solid, like the brim of the hat? Liquid? Two hundred more years passed before Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell conclusively demonstrated that the ring — by now recognized to have gaps and generally referred to as plural — could be nothing more than a vast swarm of small particles in separate orbits about the planet, so close together as to appear as a solid sheet.

If there’s a lesson in the story of Saturn’s ring, it is this: We see what we expect to see, and take comfort in the familiar.

We want powerfully to believe that the world conforms to whatever orthodoxy we learned as children. It is astonishing with what ferocity we will sometimes defend our prejudices, and it takes a rare courage to admit that our particular understanding might be wrong.

What most sets Galileo apart from his contemporaries was his willingness to confess his ignorance. When Saturn’s presumed companion satellites inexplicably disappeared, he wrote: “The unexpected nature of the event, the weakness of my understanding, and the fear of being mistaken, have greatly confounded me.”

One can take Galileo’s cry of self-doubt as the beginning of modern science.

Galileo, Huygens, and others between struggled against their preconceptions to understand what they were seeing through their telescopes. They learned that nature has a way of confounding our most earnestly held convictions.