Originally published 4 February 2003

Perhaps no other scientist has attracted more biographers than Charles Darwin. And deservedly so. No other scientist has had a more profound effect on how we understand ourselves and our place in nature.

Darwin had only one great idea — evolution by natural selection — and that idea was not uniquely his own. But he understood the idea so fully that even today his thoughts seem as fresh and relevant as ever.

Various biographers have considered Darwin in the context of his science, his psychology, his youthful adventures, his health, his relationships with his peers, and the impact of his ideas on society. Now a new biography by Darwin’s great-great-grandson, Randal Keynes, approaches the great man as husband and father.

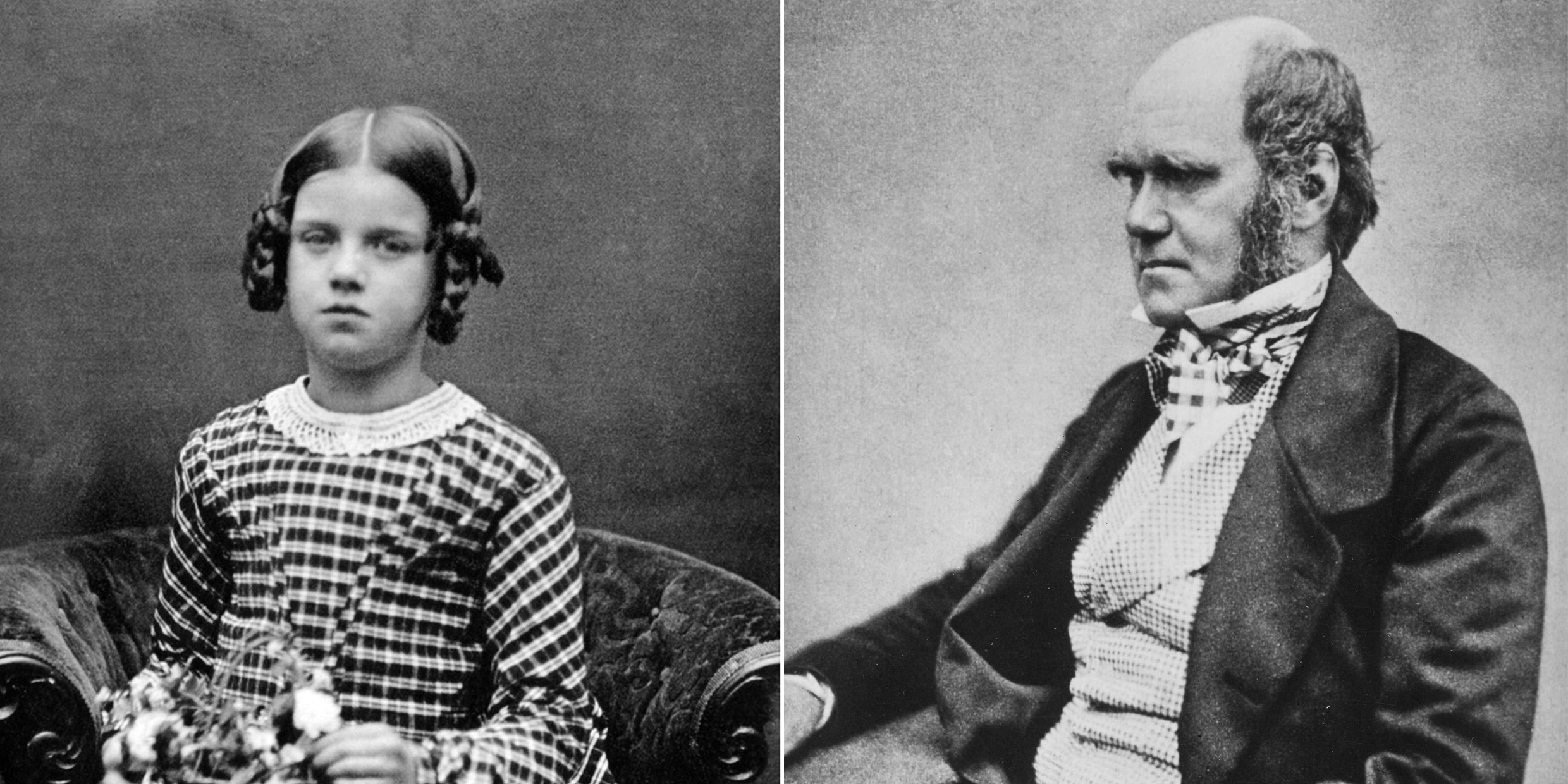

Charles Darwin, His Daughter and Human Evolution is a portrait of the scientist amid the bustling domesticity of his family home in the countryside southeast of London. The title refers to his treasured eldest daughter, Annie, who died at the age of 10, presumably of tuberculosis.

Annie’s death in 1851 is the lens through which Keynes examines the development of Darwin’s ideas about God and human nature. During his daughter’s illness, Darwin was at Annie’s bedside day and night. Her death gave poignant meaning to his developing notions of the amorality of nature and the struggle of all creatures for survival.

When Darwin returned from his five-year voyage on HMS Beagle, at age 27, he considered in his methodical way the pros and cons of married life. He settled finally on the pros, and proposed to Emma Wedgwood, his first cousin and childhood companion.

During their engagement, Darwin told his pious fiancée about his growing doubts regarding Christian revelation. He had seen enough evidence of ancient life to know that the world was older than the thousands of years allotted by Genesis, and seen enough inherent cruelty in nature to doubt the existence of an all-powerful, loving God. He doubted, too, the promise of an afterlife.

Emma’s religion was an affair of the heart, not the intellect. The hardest thing for her to bear was the possibility that Charles, by his doubts, had forfeited their chance of being reunited in heaven. Throughout their married life, their religious differences lay like a dark shadow between them, but each respected the other’s beliefs. Together they had nine children.

Annie’s death was a test of Emma’s faith and Charles’ doubts.

A widely held view among Christians at that time was that death is due to sin — either the victim’s, another person’s, or Adam’s. Most assuredly, Emma did not blame Annie. If she thought Charles’ apostasy was implicated, she did not say so. Since God cannot cause evil, she assumed that Annie’s death must be meant for the good in some mysterious way.

Charles, on the other hand, did not believe there was any divine purpose behind Annie’s death. Death was a purely natural process, part of the machinery of life that drove evolution towards “endless forms most beautiful.”

The only comfort Charles had at Annie’s death was that during her brief life he had never spoken a harsh word to her. He was distressed that he might be responsible for her death, not through his apostasy, but through heredity; he was sickly all his life.

Humans are animals, Charles believed, and like all animals we are locked in a struggle for existence that, left to itself, eliminates the weak. But humans can escape from the relentless logic of natural selection, he believed. By caring for the sick and weak, we lift ourselves above our animal natures.

Charles’s attendance on Annie was unwavering. He never doubted our responsibility to cherish the least advantaged — “the noblest part of our nature,” he called it. He strongly opposed what came to be called “social Darwinism,” the natural rule of the strong.

After his daughter’s death, Darwin put the notion of a loving God behind him. The Creator he now found in nature was, in Keynes’s words, “a shadowy, inscrutable and ruthless figure.”

Charles himself was far from shadowy, inscrutable and ruthless. He was open, forthright and kindly, and even in his grievous bereavement he continued to see “the face of nature bright with gladness.”