Originally published 6 July 1998

Legend has it that Adam was allowed by the Creator to name all the creatures of the Earth.

A daunting task! According to biologists, there may 100 million living organisms. That means if Adam thought up a name a minute for 16 hours a day (Sundays excluded), it would take him hundreds of years to complete his job.

One can assume that he began with a basic vocabulary and then improvised. For example, it is easy to see how he came up with “duck” for the aquatic bird that dips its head under water; he already had “duck” the verb, meaning “to dip quickly.”

“Duck-billed platypus” would have then been a cinch for the flat- snouted, flat-footed semi-aquatic egg-laying mammal. “Platypus” means “flat-footed” in Greek, and we can assume that Adam knew his Greek. (Was this before Babel? Oh, well, we are being whimsical, let it pass.)

And so it went, decade after decade, century after century, until Adam could look about him and speak the name of every creature.

It’s a lovely story, and provides a sort of answer to the question that puzzles every child: How do things get their names? Every place, every plant, and animal: Somewhere, sometime, somebody came up with a tag.

What about heavenly bodies? Who named the planets and stars?

Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, has its name from a Greek word for “scorching.” “Betelgeuse” may derive from an Arabic construction for “armpit,” and refers to the star’s place in the constellation Orion. Who first applied these names? No one knows.

The Romans named the planet Mercury after the speedy messenger of the gods, because it moved so quickly in its track. The planet Venus was named after the goddess of love because it was considered the most beautiful of heavenly bodies.

Mars was called for the god of war because of its blood-red color. When the planet’s two tiny moons were discovered by Asaph Hall in the late 19th century, he gave them the names of the mythological steeds who drew the war god’s chariot: Phobos and Deimos.

The planet Jupiter took its name from the chief god of the Roman pantheon, which turned out to be appropriate, since we now know that Jupiter is the largest and most massive planet in the solar system.

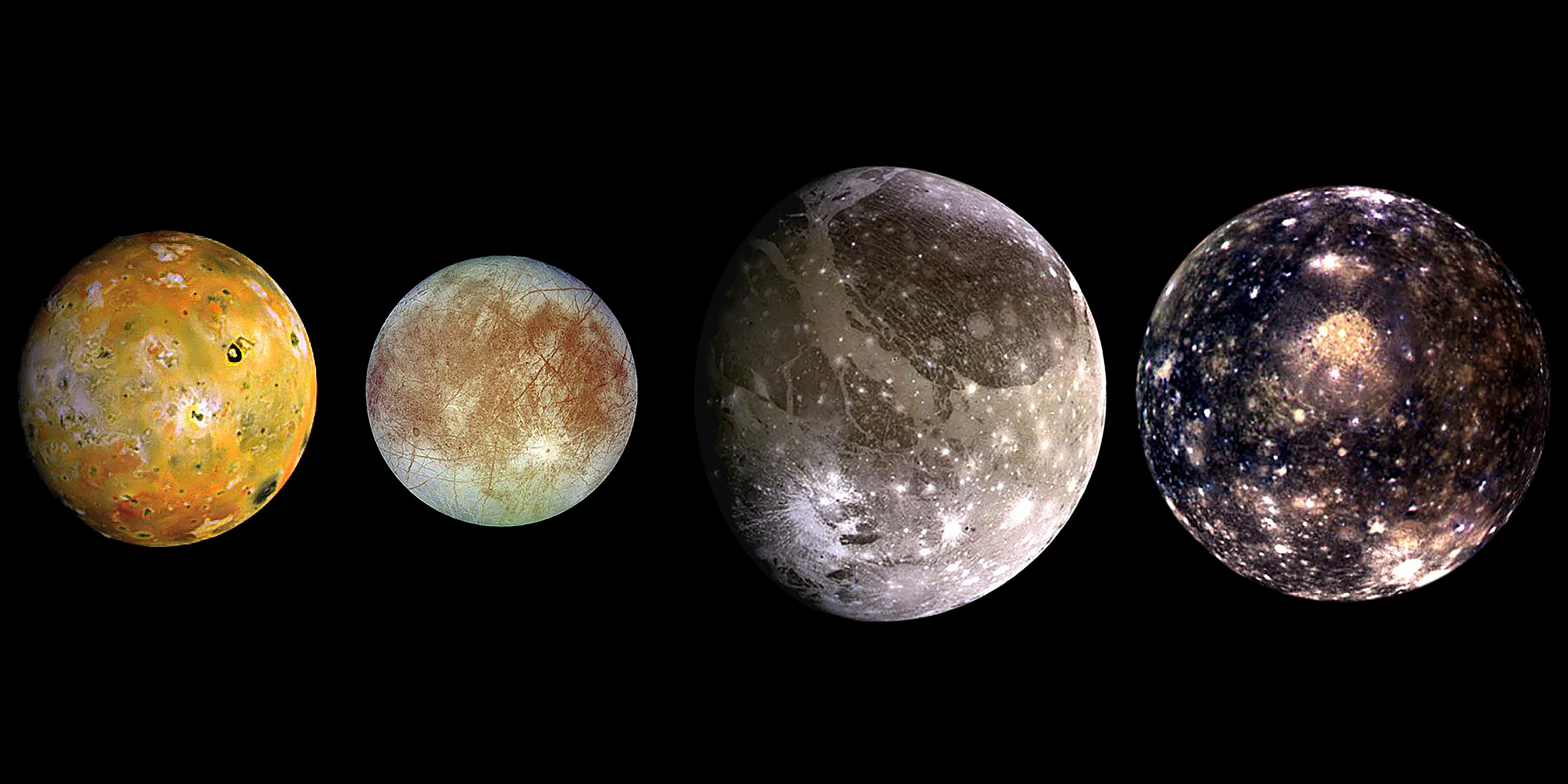

In the winter of 1610-11, Galileo observed that Jupiter had four moons. He named them the Medician Stars, after his patron Cosimo II de’ Medici, and distinguished them with Roman numerals. The German astronomer Simon Marius claimed (unsuccessfully) to have discovered Jupiter’s moons before Galileo; in 1613 he proposed naming the Jovian satellites Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto after four of Jupiter’s illicit loves. These names stuck.

Subsequently, a dozen smaller Jovian moons were discovered. Some of these also bear names of the randy deity’s illicit paramours.

The space age has given a mighty boost to the name game. The geographies of planets, moons, and even asteroids of our solar system have now been explored, with their craters, mountains, valleys, rills, and plains. Astronomers have been thrust into the position of poor old Adam, who had to come up with more names than might seem possible.

The International Astronomical Union has adopted certain nomenclature guidelines to avoid chaos. In general, it requires that naming schemes established early in the history of astronomy be continued. For example, lunar features must be Latin or Greek, Uranian moons are named for characters from Shakespeare and Pope, the names of Neptune’s satellites have a watery theme.

To avoid controversy, no names having a political, military, or religious significance are allowed. Persons being honored must have been deceased for at least three years before his or her name can be attached to a feature, except in the case of living astronauts or cosmonauts.

And so on.

Consider, for example, the task faced by astronomers attempting to assimilate the wealth of geographical detail recently observed by the Galileo spacecraft on just one of Jupiter’s moons: Europa.

By agreement, names of most features will be drawn from Celtic mythology. Craters will be named for Celtic gods and heroes, large ring features after Celtic stone circles, plains after places associated with Celtic myths.

Clearly, not even the richness of Celtic myth will be sufficient to designate every feature of European geography that will be observed during future explorations. At some point, the officially sanctioned naming scheme will break down and space explorers will lapse into Adam mode, cobbling together whatever names work — the geographical equivalents of duck-billed platypus.

We live in a universe of inexhaustible diversity, but behind the diversity there are a finite number of material particles and ordering principles out of which the world is made. That’s why science is possible. Likewise, language has a finite number of root meanings and ordering principles that can be combined in an inexhaustible number of ways. And that’s why it’s possible to come up with a name for every feature of the world.