Originally published 11 August 1996

VENTRY, Ireland — Last week’s announcement [in 1996] by NASA of evidence of life on Mars was top-of-the-front-page news in this remote corner of Ireland. The mere hint that life may once have existed on our neighboring planet stirred considerable excitement. On the morning after the announcement, folks stood around the village post office, newspapers in hand, wondering what it means.

The buzz came from somewhere deep within our collective psyche.

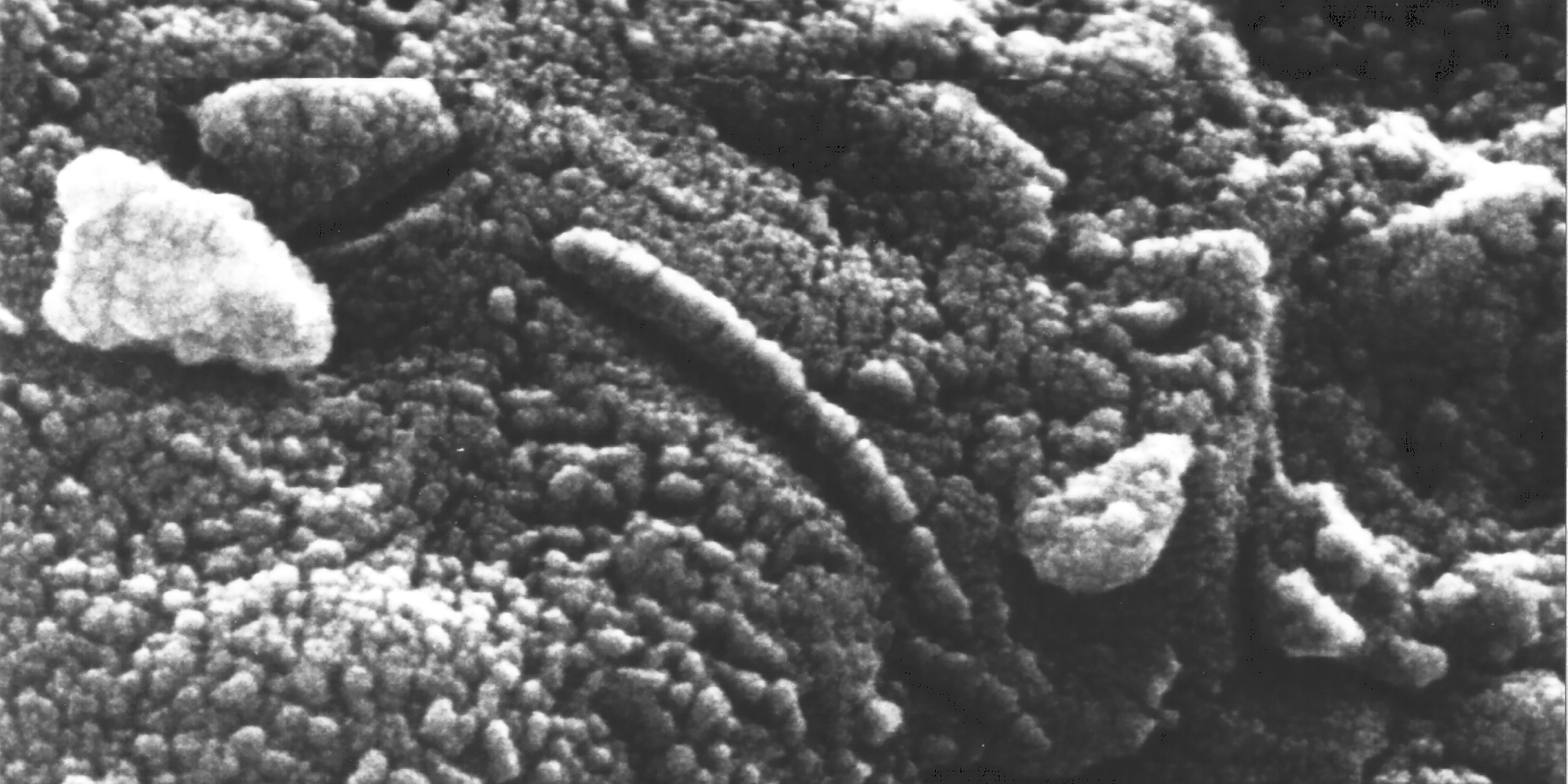

The gist of the news was clear enough: A meteorite picked up on the Antarctic ice cap in 1984 was found to contain organic compounds of a type sometimes associated with biological activity, along with microscopic impressions that may be fossils of bacteria-like organisms.

Bubbles of trapped gas in the potato-sized meteorite are similar to the Martian atmosphere sampled by Viking spacecrafts in the mid-1970s. The rock was apparently ejected from Mars by an asteroid or comet collision about 15 million years ago, and after circling the sun many times, crashed into Earth.

The organic compounds and possible microfossils were found on fracture surfaces deep inside the meteorite. The rock itself is nearly as old as the solar system, 4.5 billion years, although the organic inclusions appear to be somewhat younger.

If the discovery is confirmed, it will be the first indication that life is not unique to the planet Earth. If life appeared on Mars at about the same time it appeared here, then the odds look good that life may be ubiquitous throughout the universe.

Our preeminence as lords of creation takes a blow.

We seem to be of two minds about this. On the one hand, we like to imagine that we are the center and meaning of it all. Traditional religion teaches that we are the purpose of creation, the apple of God’s eye, and the universe a stage for the human drama of salvation.

On the other hand, we have a long propensity for peopling the cosmos with other life forms — angels, extraterrestrials, alien abductors. The idea that life, especially intelligent life, is all over the place out there has endless fascination.

In other words, we are torn between the lessons of Bible School and the movie Independence Day. The organic chemicals and fossil-like features in the Martian meteorite touch conflicting emotional buttons.

A spokesperson for the Roman Catholic Church is quoted here as saying: “There is no proof yet, but if there were, then it would cause some sort of rethink.” A Church of England spokesperson said: “We believe that God created the whole universe, so I don’t think there could be a problem.”

For most people, the issue is probably not so much religious, as psychological: Just how special are we? But then, that question may be religious in the most primitive sense.

There’s an anecdote that touches on this question in Maurice O’Sullivan’s Twenty Years A‑Growing, an account of growing up in a tiny Irish-speaking community on the Great Blasket, an island in the Atlantic off the tip of Ireland’s Dingle Peninsula.

O’Sullivan describes an excursion as a young lad, with his friend Tomás, to attend the Ventry rowing races. It is Tomás’s first departure from the island. The two boys beg a ride in a boat to the mainland. Ashore, they climb the ridge that separates the tip of the peninsula from the rest of Ireland. When they achieve the summit, Tomás looks out in astonishment upon the parish of Ventry and the land beyond.

“Oh, Maurice,” he cries. “Isn’t Ireland wide and spacious!”

News of life elsewhere in the universe, if confirmed, will have the same effect on us as the sight of a vast Ireland rolling away, hill after hill, had on Tomás; there is a kind of awe in seeing beyond one’s known world out into a universe of unfathomable dimension.

It was something of Tomás’ wonder that one detected in the chatter of voices in the village post office on the morning after the announcement by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

But before we declare ourselves denizens of a greater cosmos, with whatever pleasure or discomfort that might entail, we need to separate the solid science from the hype. And the hype is thick in the news releases from NASA and in popular news reports. But the science is tricky, tentative, and highly technical.

Any single piece of new evidence for Martian life can be explained by non-biological processes of one sort or another. It is only when all the evidence is taken together that the circumstantial case for life on Mars in the remote past looks interesting.

The scientists who did the work are confident their case will stick. Simon Clement of Stanford University said, “It’s been a question of trying to disprove the conclusion by running as many experiments as we can. We tried as hard as we could to escape from that conclusion [of life on Mars], but haven’t been able to do that.”

This is science at its best: enthusiasm for a potentially historic discovery, balanced by organized skepticism. Glory if they get it right; egg on the face if they are wrong.

There’s many a dicey step between glory and egg. Is the meteorite of Martian origin? Did the included organic materials arrive with the meteorite or are they terrestrial contamination? Are the supposed “fossils” caused by microorganisms or are they purely physical features? If life did once exist on Mars, might it be terrestrial microorganisms blasted that way by an asteroid impact on the early Earth?

Now the fun begins as other researchers try to confirm or refute “life on Mars.” Other meteorites of a likely Martian origin (12 have been found so far) will be meticulously examined. And of course NASA will get a welcome boost in its efforts to send more missions to the red planet. Expect them to play up the new discovery for all it’s worth, while trying to appear objective. President Clinton, too, was quick to hitch his political wagon to this spellbinding hint of microscopic extraterrestrials.

It would be a mistake, however, to think of this potential breakthrough as an American triumph. It is a human achievement, celebrated worldwide. Perhaps the biggest story is the reaction itself. The question of life on Mars touches upon some of our most ancient and firmly held convictions about our specialness in the universe.

At this moment, Catholics and Protestants in the British corner of this island are toeing off against each other in another episode of sectarian hatred. In Bosnia, Chechnya, Burundi, and elsewhere on this tiny planet, humans are killing each other over differences so slight as to be almost imperceptible to outsiders.

If there is a lesson to be learned from the lively universal reaction to the teasing inclusions in the Martian meteorite, it is that we are one people on a cosmic island too small for squabbles.

Despite the initial hype, the scientific community has subsequently rejected the hypothesis that the unusual structures within Martian meteorite ALH 84001 have a biological origin. ‑Ed.