Originally published 24 October 1994

Already we hear of Armageddon, in supermarket tabloids, popular magazines, and fundamentalist pronouncements — the first tap-taps of a drum roll of superstitious fervor that will grow in intensity as we approach the end of the millennium, culminating in an apocalyptic hullabaloo in the last days of the year 1999.

Of course, because there is no year zero, two thousand years of the Christian calendar will actually have passed at midnight, Dec. 31 of the year 2000, not at the end of 1999.

But the arithmetic is simply irrelevant. The true popular millennium has nothing to do with mathematics or calendrical science. We are talking about habits of the human mind, and psychologically speaking the moment of consequence occurs when the triple nines roll over all at once to become born-again zeros.

It happened once before.

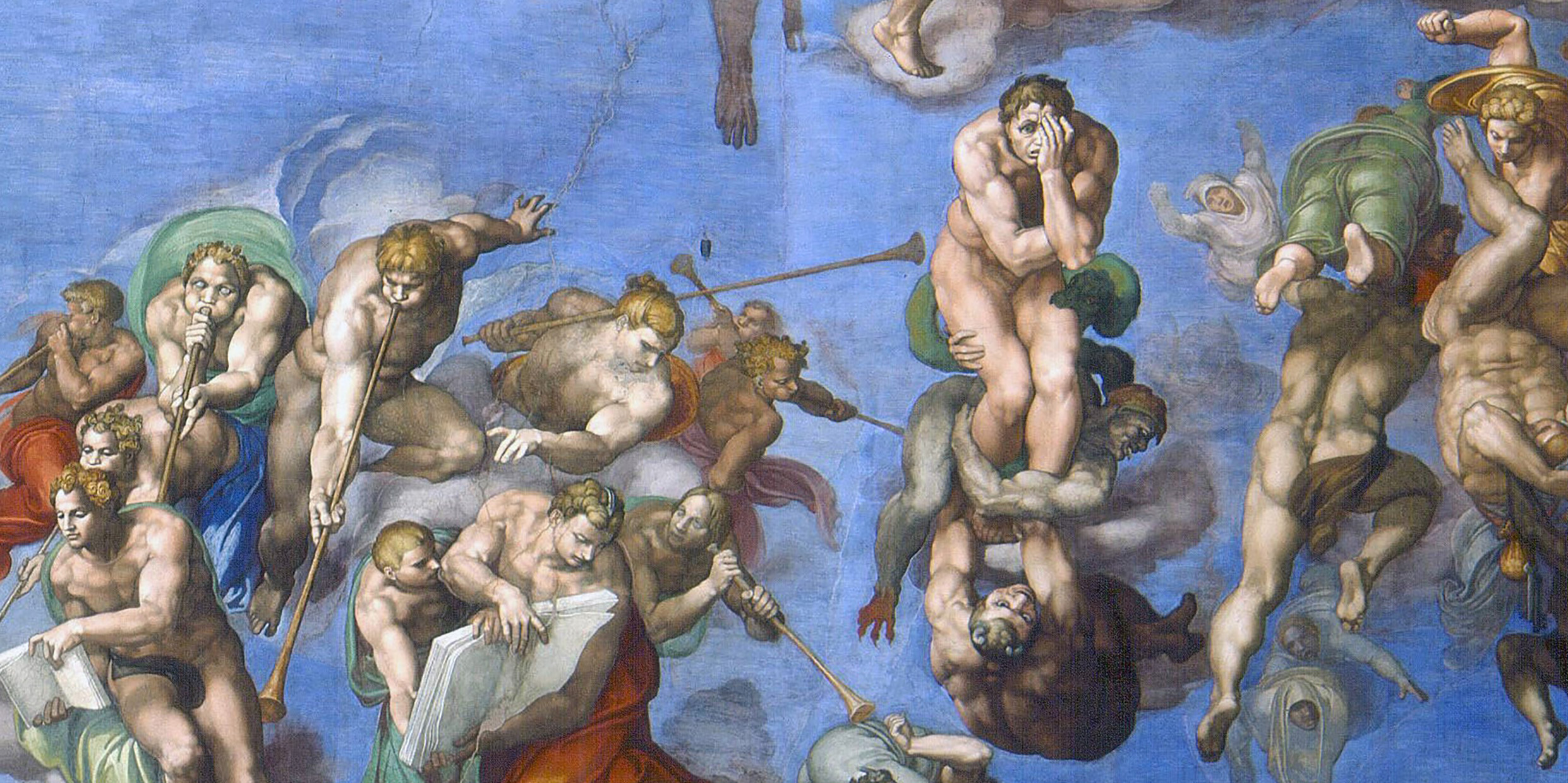

On the last day of the year 999, many Europeans anxiously awaited the trumpets to sound and the skies to open. They based their belief on a passage in the Book of Revelations: “And when the thousand years are expired, Satan shall be loosed from his prison, and shall go out and deceive the nations.”

Any 10th-century person with a bit of schooling knew that a thousand years from the presumed date of Christ’s birth would not have passed until the last day of the year 1000. But that didn’t stop the churches from being full on New Year’s Eve, 999 A.D.

Even the old basilica of St. Peter’s in Rome was packed with frightened worshipers waiting for the world to end. Pope Sylvester II celebrated midnight mass. He was not a man inclined to superstition, but the occasion seemed to call for official acknowledgement. At the words ite, missa est, (“go, the mass is ended”), the bell began to toll. Terrified eyes gazed heavenward. Mouths gasped words of contrition. Limbs shook.

One wonders if even the Holy Father, one of the most rational men of his time, did not experience a twinge of cataclysmic anxiety.

Many people expected the Last Judgment to be held in Jerusalem, and thousands of pilgrims made the arduous journey to the Holy Lands in anticipation of finding a place at Christ’s right hand when the sheep were separated from the goats. They waited at the burial place of Jesus as the hour of midnight approached.

The sand dribbled through the hourglass. Nine-hundred-and-ninety-nine years worth of sand had passed through since day one of the Christian era, and now the last grain slipped through the neck. Ite, millennium est (“go, the millennium is ended”), the priests might have intoned.

And nothing happened.

To be sure, not everyone expected the Day of Wrath. Scholars, educated clergy, and the upper nobility generally pooh-poohed millennial hysteria as so much superstition.

But those who wanted to believe that the end of the world was at hand found ample evidence for their belief.

Meteors, lightning storms, volcanic eruptions, comets, and eclipses were taken as signs of the coming Armageddon. Parts of cities burned to the ground. Brilliant lights appeared in the night sky. It mattered to no one that in those days parts of cities burned to the ground almost every year, and that

lights (auroras) appeared in the night sky with dull regularity. If one is looking for portents, nature will always oblige.

The same thing will happen in the run-up to the year 2000. Floods, earthquakes, famines, and political calamities will be offered as auguries of the impending Day of Judgment, never mind that floods, earthquakes, famines, and political calamities have always been with us. Coincidence is the science of the True Believer.

According to all accounts, the scenes of hysteria that accompanied the last day of the year 999 were not repeated a year later, when the thousand years spoken of by the Book of Revelations actually expired. But let’s face it. It’s not the end of the thousandth year that evokes excitement; it’s the arrival of the three big goose eggs.

This time around, too, on New Year’s Eve, 1999, throngs of religious millenarians will be expecting trumpets and heavenly pyrotechnics. But the less superstitious folks who organize First Night celebrations in Boston and other cities around the country will also provide a grand excess of fun events and man-made fireworks. The rolling-over of the digits calls out for recognition.

As the great day approaches, we’ll hear more and more from sticklers for accuracy who will point out the one-year flaw in calendrical logic. But who cares? When the youngster with the New Year’s sash arrives, we want the sash to read 2000, not 2001. Those zeros suggest a fresh start, a new beginning, a chance to put things right. And the old man with the scythe and the decrepit nines will depart, taking with him another thousand years of our worldly cares and woes.