Originally published 8 November 1993

Imagine this. A machine made of pulleys and levers that spends its time scooping machine oil from a pool at its base and pouring it over itself. The oil glides sensuously down over the mechanism, back into the pool. Ahhh!

Or this. A machine mounted on wheels that you push like a barrow. As it rolls, a cogged mechanism causes an artificial hand to write on a white piece of paper “Faster!” The faster you roll the cart, the more manically the machine scrawls its urgent message.

What’s all this? It’s an exhibit of Somerville sculptor Arthur Ganson’s witty machines. Within seconds of stumbling onto it, I was in hysterics.

A bird cage filled with a delicate wire mechanism that repeatedly tips two of those cylindrical cardboard toys that make animal noises when you turn them. These tweeted. The title: Two Cans from the Island of Taiwan.

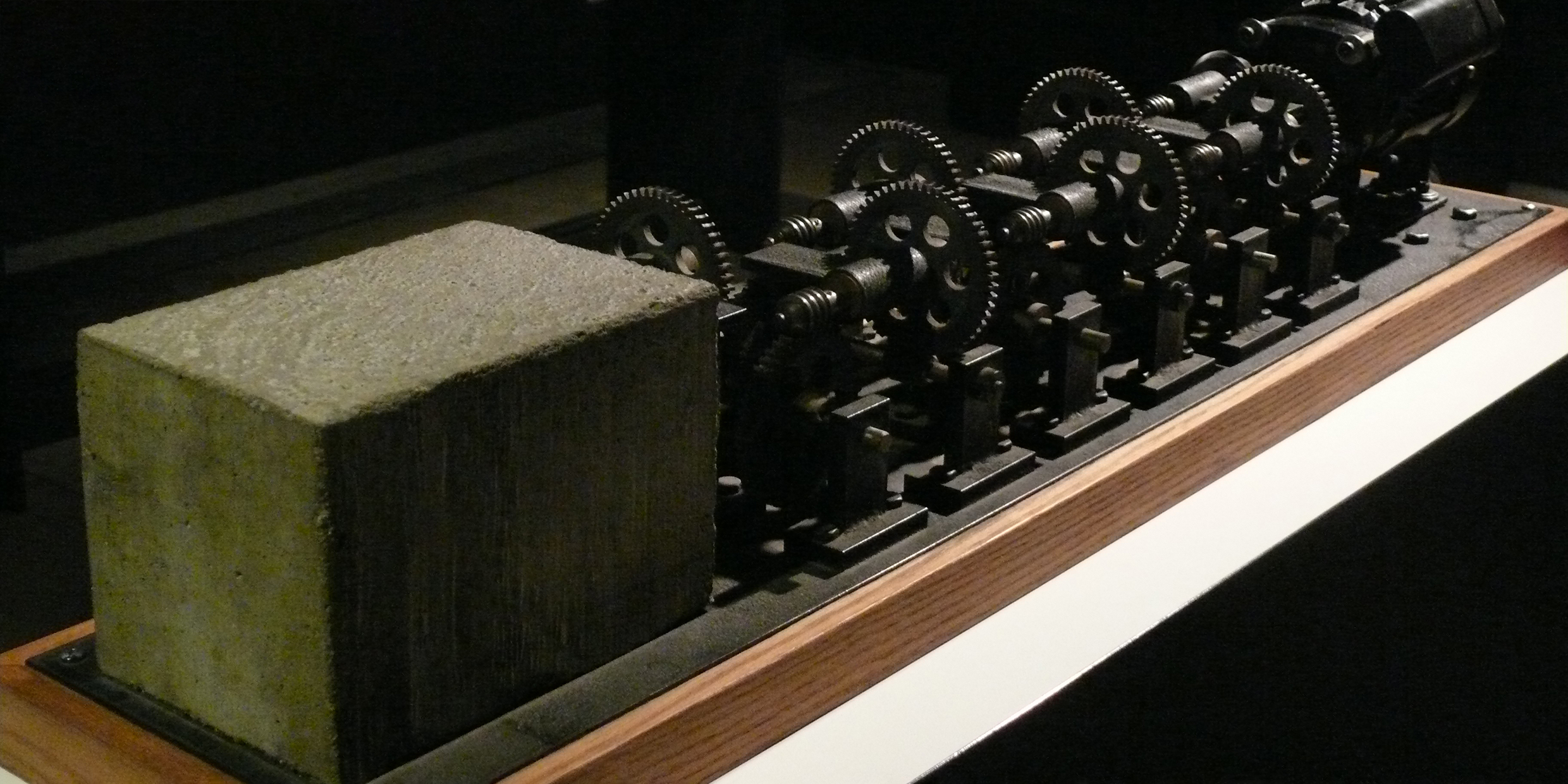

A train of 12 worm gears, each gear driving the next at a fifty-times slower rate. The first gear whirls furiously. The last gear is embedded in concrete. What’s so funny? I’m not sure, but I laughed uproariously.

It was a treat to be around machines that made me laugh. Machines with wit. We spend most of our days with machines that haven’t a funny bone in their mechanical bodies. Machines that turn us into dour button-pushers.

Of course, we shouldn’t blame the machines. It’s their industrial designers that are humorless, those glum-faced consortiums of engineers that give us our daily mechanisms.

In 1738, the mechanical wizard Jacques de Vaucanson demonstrated his masterpiece before the court of Louis XV, a copper duck that ate, drank, quacked, flapped its wings, splashed about, and, to the astonishment of all, digested its food and excreted the remains. It was a witty beginning for the age of machines. The king’s courtiers had a good titter.

Descriptions of Victorian inventions in early editions of Scientific American also suggest a delightful sense of whimsy. Electric jewels. Cuckoo watches. A mustache food-and-drink guard that clips into the nostrils. Advertising projected onto clouds. An electric trolley on tracks that delivers food from the kitchen directly to the diner’s place.

The Victorians liked whacky combinations. A hammock mounted on a tricycle that allows the cyclist occasional rest. A camera hat. A rocking chair connected to a cradle and butter churn that employs “hitherto wasted female power” to sooth the baby and make butter while keeping the hands free for “darning, sewing, or other light work.”

Now that I think about it, maybe it is only in retrospect that we find these things funny. Never mind; Victorian inventors at least understood that machines are our servants rather than the other way round.

It is the artists who teach us not to take our machines too seriously.

The French Dadaist artist Marcel Duchamp saw the humorous possibilities of a bicycle wheel mounted on a stool, or an ordinary urinal turned upside down and titled Fountain. His masterpiece, a glass construction called The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, although not quite a machine, is full of wires and painted mechanisms. Duchamp found it necessary to invent a new “amusing physics” to describe this last work, including terms like “oscillating density,” “uncontrollable weight,” and “emancipated metal.”

The undisputed master of whimsical machines is the Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely, who contrives spindly wire devices that thumb their noses at Swiss order and efficiency. Those whoo have seen them say Tinguely’s animated sculptures invariably produce laughter as they click, whir, and clatter unpredictably, and even photographs of his works produce a smile.

Tinguely’s most famous sculpture is called Homage to New York, a vast white contraption of wheels, motors, pulleys, and wires that was designed to destroy itself in the garden of the Museum of Modern Art. The machine balked short of suicide, but caused an uproarious commotion before the fire department arrived to put it out of its misery. Tinguely was delighted with the unexpected outcome.

“For me,” says Tinguely, “the machine is above all an instrument that permits me to be poetic. If you respect the machine, if you enter into a game with the machine, then perhaps you can make a truly joyous machine — by joyous I mean free. That’s a marvelous thing, don’t you think?”

Yes, I do think so, and that’s the delight of Arthur Ganson’s incredibly whimsical, utterly free creations. One of those creations is titled Homage to Tinguely’s Homage a Marcel Duchamp, which places Ganson squarely in a poetic, joyous tradition. Next year he will bring his whimsy to the heart of technology as artist-in-residence at MIT.

What is Ganson up to? He is not interested in making political statements, he says. “My machines are investigations of thoughts, dreams, and ideas.”

“They are about invention, about play, about a childlike way of looking at the world. They are about not taking the world too seriously.”

I suspect that Ganson takes the world more seriously than do those of us who surrender our lives to humorless machines. Like Jean Tinguely before him, he knows that a spirit of play lies at the heart of the world.

Be sure to visit Arthur Ganson’s website for more of his whimsical machines. ‑Ed.