Originally published 2 April 1990

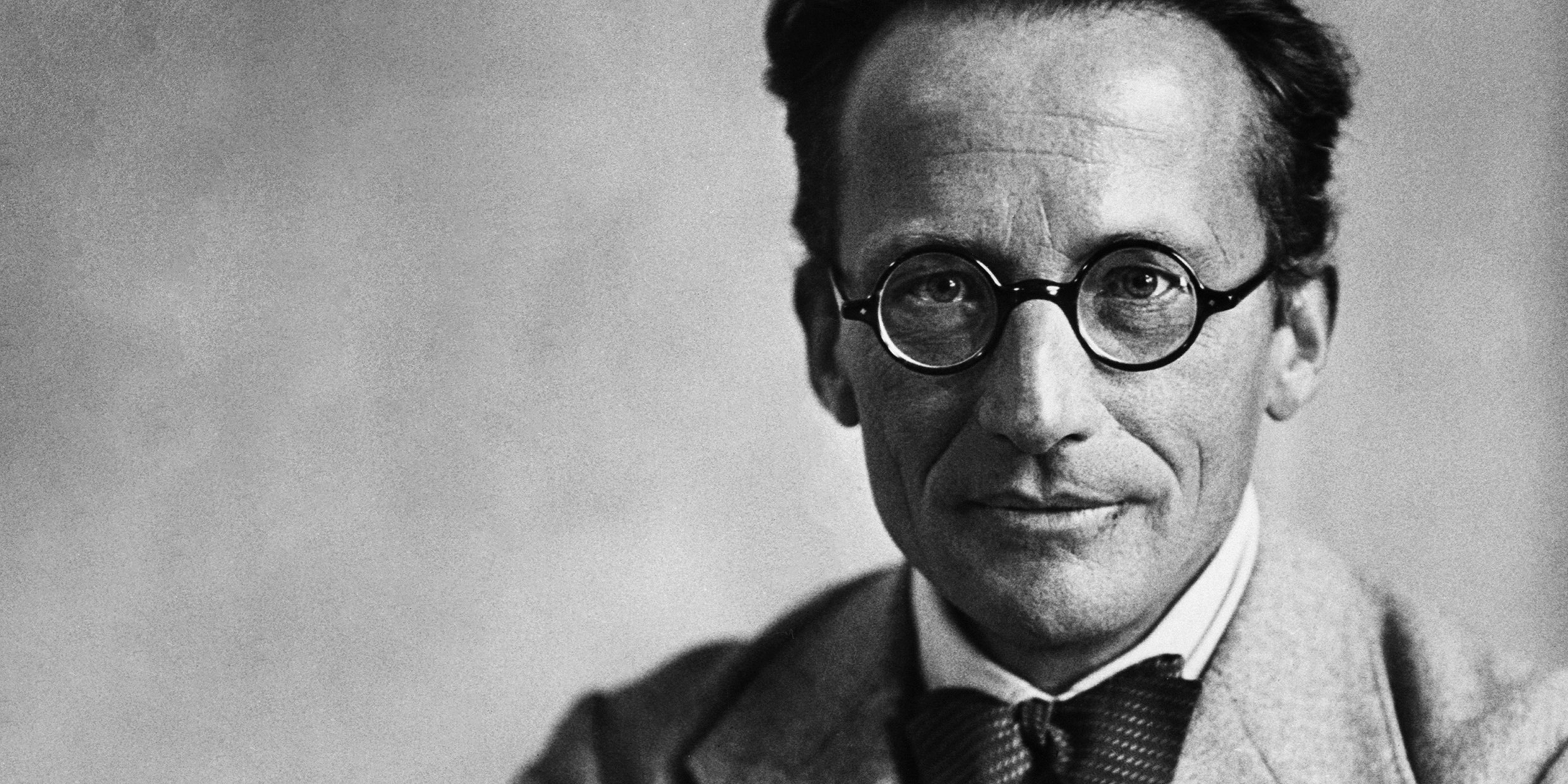

In the year 1926, his annus mirablis, the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger published four papers laying down the foundations of a new theory of nature, called wave mechanics.

J. Robert Oppenheimer called Schrödinger’s theory “perhaps one of the most perfect, most accurate, and most lovely [that] man has discovered.” Einstein saw the work spring from “true genius.” Walter Moore, Schrödinger’s recent biographer, says flatly of the theory “there is nothing more beautiful in theoretical physics.”

At the heart of the theory is a single equation, universally called Schrödinger’s equation, whose solutions are undulations or waves. Within the solutions is contained much of physics and, in principle, all of chemistry. In Schrödinger’s theory, the entire universe resonates like a marvelous piece of music.

Schrödinger’s wave mechanics was a culmination to the quantum revolution in physics, begun by Planck, Einstein, Bohr and de Broglie earlier in the century. The revolution had these effects:

- It dismissed the philosophy of materialism that had dominated physics since the time of Newton.

- It showed that everything in the world is part of everything else.

- It did away with strict determinism and predictability.

- It restored the human observer to a central position in natural philosophy.

This stunning revolution in human thought was given elegant and concise expression by Schrödinger’s theory. The physicist Arnold Sommerfeld said of Schrödinger’s discovery, “It was the most astonishing among all the astonishing discoveries of the 20th century.”

Where do such discoveries come from? What was going on in the mind of 38-year-old Erwin Schrödinger in the year 1926 that led to this burst of mathematical creativity? It is the task of the scientific biographer to elucidate the springs of genius, and this Walter Moore does admirably in his new biography, Schrödinger: Life and Thought (Cambridge University Press).

His conclusion is both surprising and controversial: Schrödinger’s scientific creativity was promoted and sustained by erotic tension.

Surprising because we have an image of the mathematical scientist standing aloof from matters of the flesh, a kind of white-coated pilgrim of pure thought.

Controversial because we hate to see our heroes with feet of clay. Schrödinger, it turns out, was a womanizer for whom no female was out of bounds. Neither tender age nor marital status were detriments to his covetous philanderings.

Schrödinger’s biographer is a physical chemist, presently at the University of Sydney, and eminently qualified to lead us through the physical and mathematical subtleties of Schrödinger’s thought. The book is a successful biography on that basis alone. But the key to Schrödinger’s creative life, according to Moore, is to be found in his private diaries, where the physicist dutifully recorded the names of all his loves with a code to indicate the denouement.

One particular affair seems to have been crucial to the development of his physics.

Theoretical physics is basically a young man’s game. Revolutionary breakthroughs are usually achieved before the age of thirty. At the age of 37 Schrödinger was deeply versed in the techniques and problems of modern physics, but had achieved nothing of major consequence. His marriage of 5 years to Annemarie Bertel was at its low point of disagreement and tension. It was a classic moment for a mid-life crisis.

Then, over the Christmas holidays of 1925, Schrödinger went off to a hideaway in the Alps with an old girlfriend. We do not know her name because the diary for that year is lost. Apparently, it was an extraordinary assignation. In the midst of his dalliance, wave mechanics was invented. Says Moore: “Whoever may have been his inspiration, the increase in Erwin’s powers was dramatic, and he began a twelve-month period of sustained creative activity that is without a parallel in the history of science.”

Despite its many tortured convolutions, Schrödinger’s marriage to Annemarie Betel lasted until his death, and ended on a note of mutual devotion. But until the end he seemed to be convinced that his continued scientific creativity required an erotic charge. Poems of seduction and higher mathematics occupied his energies in almost equal measures.

Late in his life Schrödinger wrote to his friend the physicist Max Born; “For I have no higher aim than to work out the beauty of science. I put beauty before science. Nitimur in vetitum [Ovid: we strive for that which is forbidden]. We are always longing for our neighbor’s housewife and for the perfection we are least likely to achieve.”

Greatness in science, like greatness in art, is not always accompanied by an attractive personality. Good scientific biography helps us recognize the humanness of science. It does not necessarily follow that we’ll like what we see.