Originally published 12 February 1990

In an essay published after her death, novelist Virginia Woolf wrote about special “moments of being” that sometimes interrupt the gray, nondescript “cotton wool” of everyday life. One of those moments occurred as she was looking at a flower in a garden at St. Ives, in England. It was an ordinary plant with a spread of green leaves. She looked at the flower and said, “That is the whole.”

It had suddenly occurred to her that the flower was part of the earth, part of everything else that was. The realization came, she said, as a hammer blow, and from it emerged a philosophy: Behind the cotton wool is hidden a pattern. The whole world is a work of art and we are part of it.

It would be easy to dismiss this revelation as so much sentimentality, but Virginia Woolf was anything but sentimental. Many of her moments of being brought with them a peculiar horror. For her, the recognition that we are at one with the world could be a source of both exhilaration and despair.

Woolf’s interest in the connectedness of things was not that of a mystic, but of a writer. “We are the words,” she wrote, describing the experience of the flower. “We are the music; we are the thing itself.”

Breaking connections

The scientist is no less sensitive than the writer to the connectedness of things, to the pattern hidden behind the cotton wool. But in practice, science works by breaking connections, by isolating, by fracturing the world into a myriad parts like a shattered crystal. What is the laboratory bench but a bare arena for isolating one thing from the rest of the world? What is an experiment but an attempt to reduce the many variables in experience to one?

This shattering of the world into isolated parts may account for the alienation of popular culture from science. We value wholeness. We thrive on those moments of being when we sense the completeness of things. “Wholeness,” wrote Virginia Woolf, “means that [experience] has lost its power to hurt me.”

Most people respect science. They know that our health and economic well-being depend in large measure on scientific knowledge of the world. At the same time, they distrust science. They find it reductionist, fragmenting, remote from experience, and especially remote from those special moments when we glimpse something whole and entire.

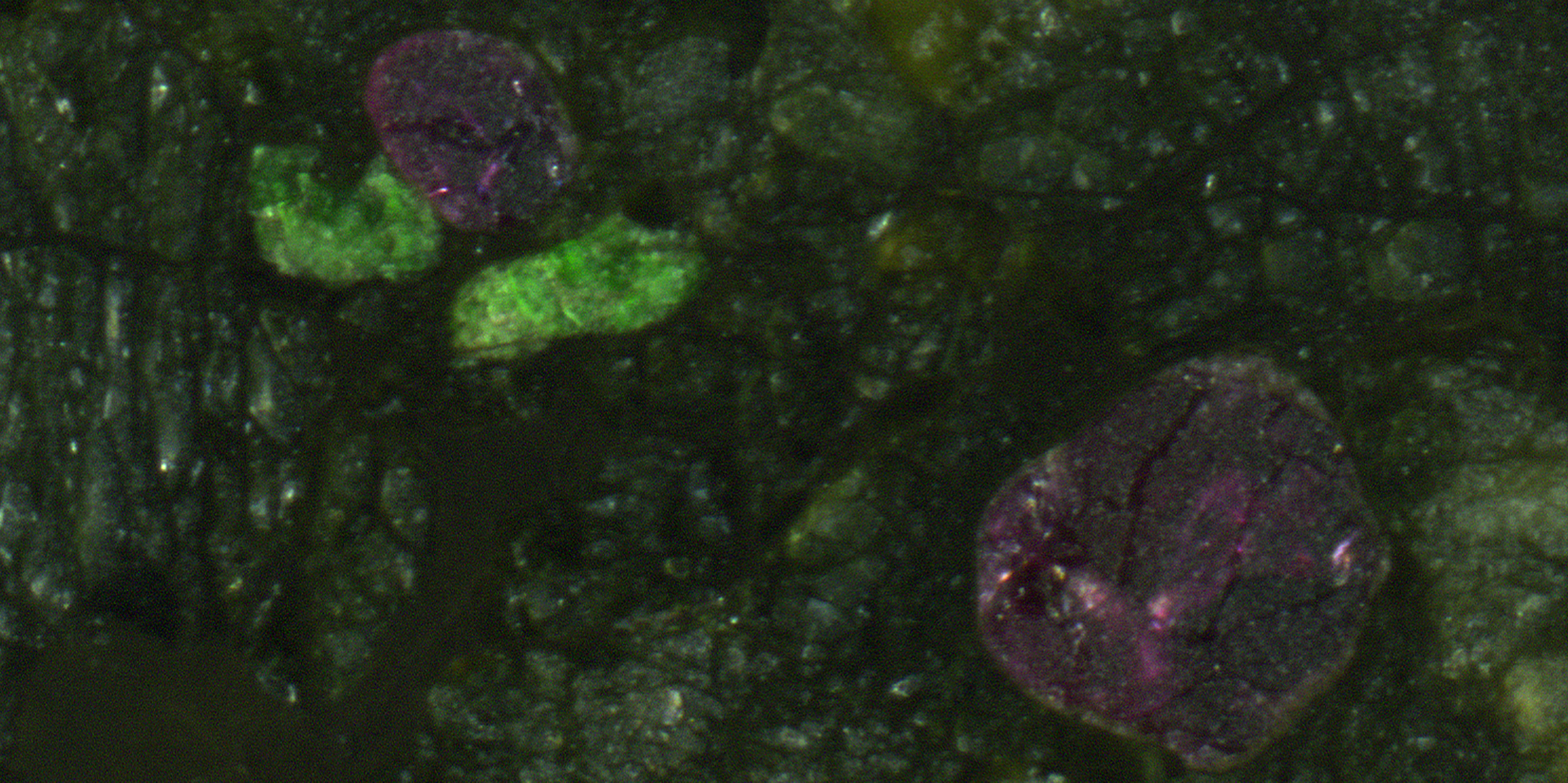

But science too can provide special moments when the wholeness of things becomes apparent. As I write, I am looking at the cover of the June 23, 1989, issue of Science. It is a photograph of a garnet crystal shaped like a paisley swirl, about the size of a bottle cap but enlarged to fill the page. The crystal is embedded in a matrix of ancient metamorphosed granite broken from a mountainside in Vermont. The garnet crystal is a fragment of a mountain that embodies the history of the mountain itself.

Geologists John Christensen, John Rosenfeld, and Donald De Paolo of the University of California extracted the garnet from the mountainside where it had been exposed by eons of erosion. They sliced the crystal into thin segments and used radioactivity to measure the ages of segments along the sweep of the “paisley” swirl. The little cap-sized garnet grew at a rate of about 1.7 millimeters per million years for 10 million years.

Deep in the earth

All of this happened deep in the earth as the ancestral Green Mountains were being thrust upwards, about 380 million years ago. At that time, the drifting continents of northern Europe and Africa were approaching North America from the south. The resulting collisions would form the supercontinent geologists call Pangaea.

The squeeze of slowly converging continents folded the rocks of Vermont into an S‑shaped loop called a nappe (from the French for “tablecloth”). Meanwhile, the garnet crystal was growing from a reservoir of molten minerals, adapting its shape to stresses in the rock. The paisley shape of the crystal is a miniature image of what was happening to the mountains themselves.

The ancient mountains of New England are now almost gone, erased by erosion, but the surviving garnet crystal enables geologists to deduce the rate at which those mountains were heaved upwards, stretched, folded, and implanted with granite. The crystal is a miniature record of 10 million years of continental collision and mountain building — 10 million years of the geologic history of New England. It is not quite William Blake’s universe in a grain of sand, but close to it.

It is part of the connectedness of the world that the whole is very often contained in the part. That much, at least, mystics, writers, and scientists have in common. Seeing the photograph of the garnet on the cover of Science was a kind of moment of being, a real and present image of colossal geological events that I had previously imagined only in my mind’s eye. I looked at the photograph and said, “That is the whole.”