Originally published 3 July 1989

When the 3rd revised edition of Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary appeared back in 1961 we saw in the new words a mirror of ourselves. Breezeway. Split-level. Fringe benefit. Airlift. Beatnik. Zen. Den mother. No-show. Astronaut.

Now, in 1989, comes a new edition of that most monumental of all dictionaries, the Oxford English Dictionary, and again we find an image of ourselves in the new vocabulary. Fast track. Palimony. Diskette. Acid rain. Microwavable. Happy hour. Plastic money. Nose-job. Brain dead. Crack. Barf. Bad.

Bad? Of course. In its new meaning, “excellent.”

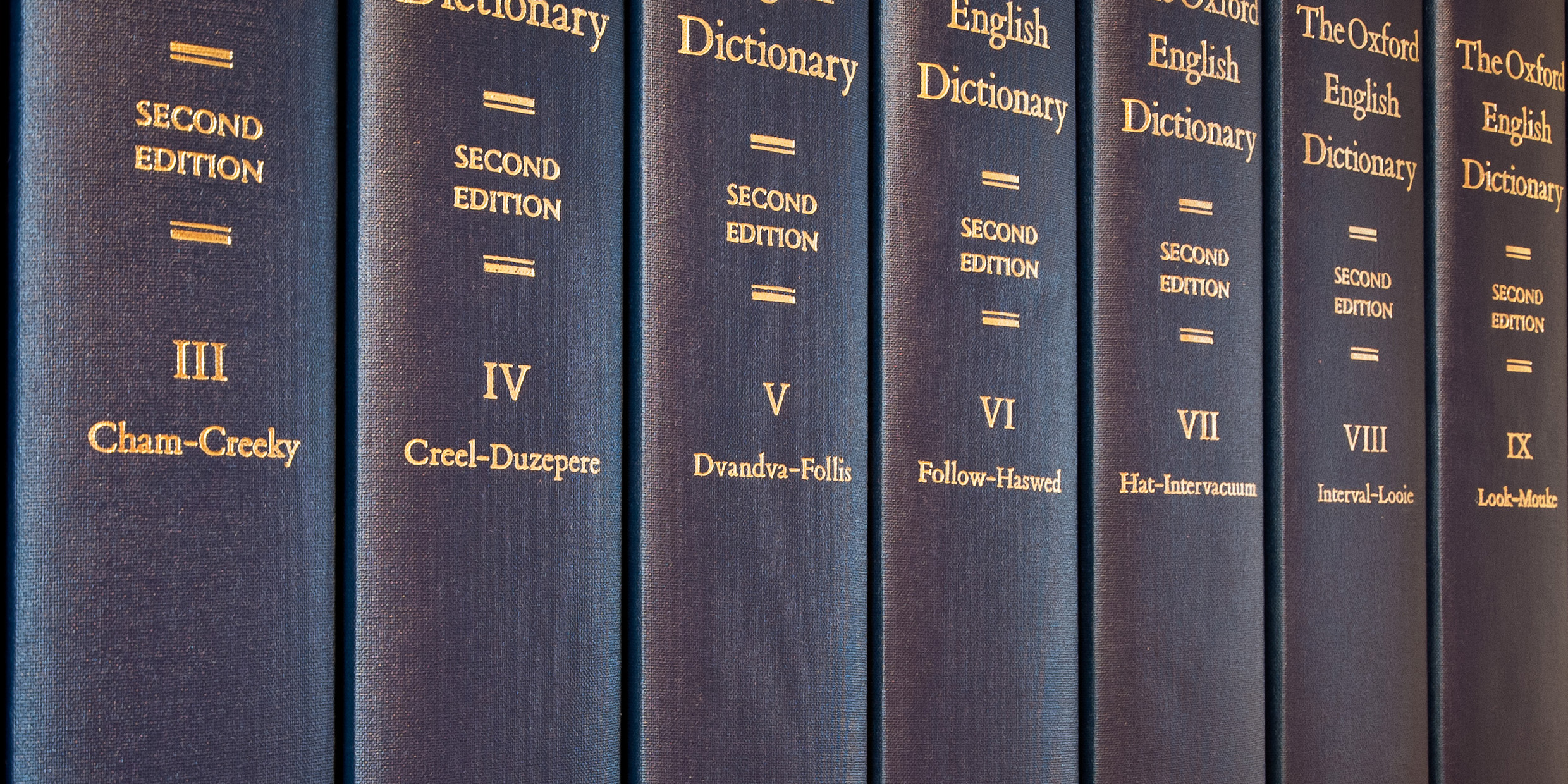

The price tag for this somewhat disconcerting portrait of ourselves is $2,500. Twenty thick volumes, incorporating the 12-volume edition of 1932, four supplements compiled between 1972 and 1986, and 5,000 new entries. Monumental. Exhaustive. Illuminating. Exhilarating.

The OED is to the English language what Gray’s Anatomy is to the human body and Britton and Brown’s Flora is to the plants of North America. The definitive description. The classic mapping of our mother tongue. A stupendous achievement of linguistic cartography.

Ecology of language

The writer Peter Farb once suggested that there is an “ecology” of language: “the web formed by strands uniting the kind of language spoken, its history, the social conventions of the community in which it is spoken, the influence of neighboring languages, and even the physical environment in which the language is spoken.”

The ecology of English must begin where any science begins, with exact description of the object of study. The new OED compiles more than half-a-million words or terms that have formed the English vocabulary from the times of the earliest records to the present day, with all the relevant facts concerning their form, sense-history, pronunciation, and etymology, illustrated with more than 2 million excerpts from the literature of every period. As such, it is more than just a tool for writers (for that I’ll stick to my Webster’s II); it’s a history, a geography, a psychology, and a sociology of the human mind, or at least the English-speaking mind.

Consider just one of the new entries: nerd. Not quite the same as the American almost-synonym “square,” or the British “swot.” The OED generously documents nerd with quotes from the 50s and 60s. And what is the origin of the word? Two possibilities. Perhaps from Dr. Seuss’ If I Ran the Zoo, published in 1950 (“I’ll sail to Ka-Troo And Bring Back an It-Kutch, a Preep and a Proo, a Nerkle, a Nerd, and a Seersucker, too!”). If this is where nerd came from, it left preep, proo and nerkle behind; they have no entries in the OED.

Or maybe nerd is a euphemistic alteration of another rhyming word, omitted here because, as the OED says, it is “not now in polite use,” although this latter term is documented with quotations from English literature going all the way back to the year 1000.

Shakespeare and Seuss

All of this may be more than you or I ever wanted to know about nerd, but it illustrates the richness of a work that embraces both Shakespeare and Dr. Seuss. As you might guess, Shakespeare is the source of more OED citations than any other writer (Can you guess who is second?), and it is ironic that the Bard of Avon is the last author who was required to work without a dictionary. The first English dictionary (of sorts) was published in the year of Shakespeare’s death.

It is no coincidence that the earliest word compilations appeared in the century of Galileo and Newton, or that the magnificent dictionary of Samuel Johnson is a crowning culmination of the Enlightenment.

A dictionary is scientific curiosity applied to the dark continent of language. The first edition of the OED, initiated in 1884 (and not completed until 1928), sprang from the same Victorian curiosity about word origins that sent Burton and Speke in search of the source of the Nile. The OED is to the English language what the British Museum of Natural History is to nature — a great store house of specimens, a showcase of variation, natural selection, and evolution, a physical embodiment of the Victorian passion for description and classification.

In perusing the new edition of the OED I was pleased to discover that the word “muse,” in addition to its more familiar meaning (“to ponder, meditate”) also means “to be affected with astonishment or surprise; to wonder, marvel,” a meaning not found in my Webster’s II. To muse in this latter sense is, of course, the motivation for all good science, and the OED evokes precisely this kind of musing. To muse among its pages is like pouring over detailed maps of the Earth, or spending a day in a great museum of natural history — astonished, even surprised, by the richness of a language that mirrors the richness of the world.

The entry for A, the first word in the OED, runs to six pages. The second most-quoted author is Walter Scott. And what’s the last word on this subject? Zyxt. An obsolete word from the English county of Kent meaning “see.”