Originally published 23 January 1989

“I sing the body electric,” wrote Walt Whitman. Let the poets praise the body’s galvanic spirit, moral incandescence, and currents of courage and passion. To physician-essayists Richard Selzer and Frank Gonzalez-Crussi goes the task of chronicling the body’s short circuits, frayed insulation, blown fuses, and dead batteries.

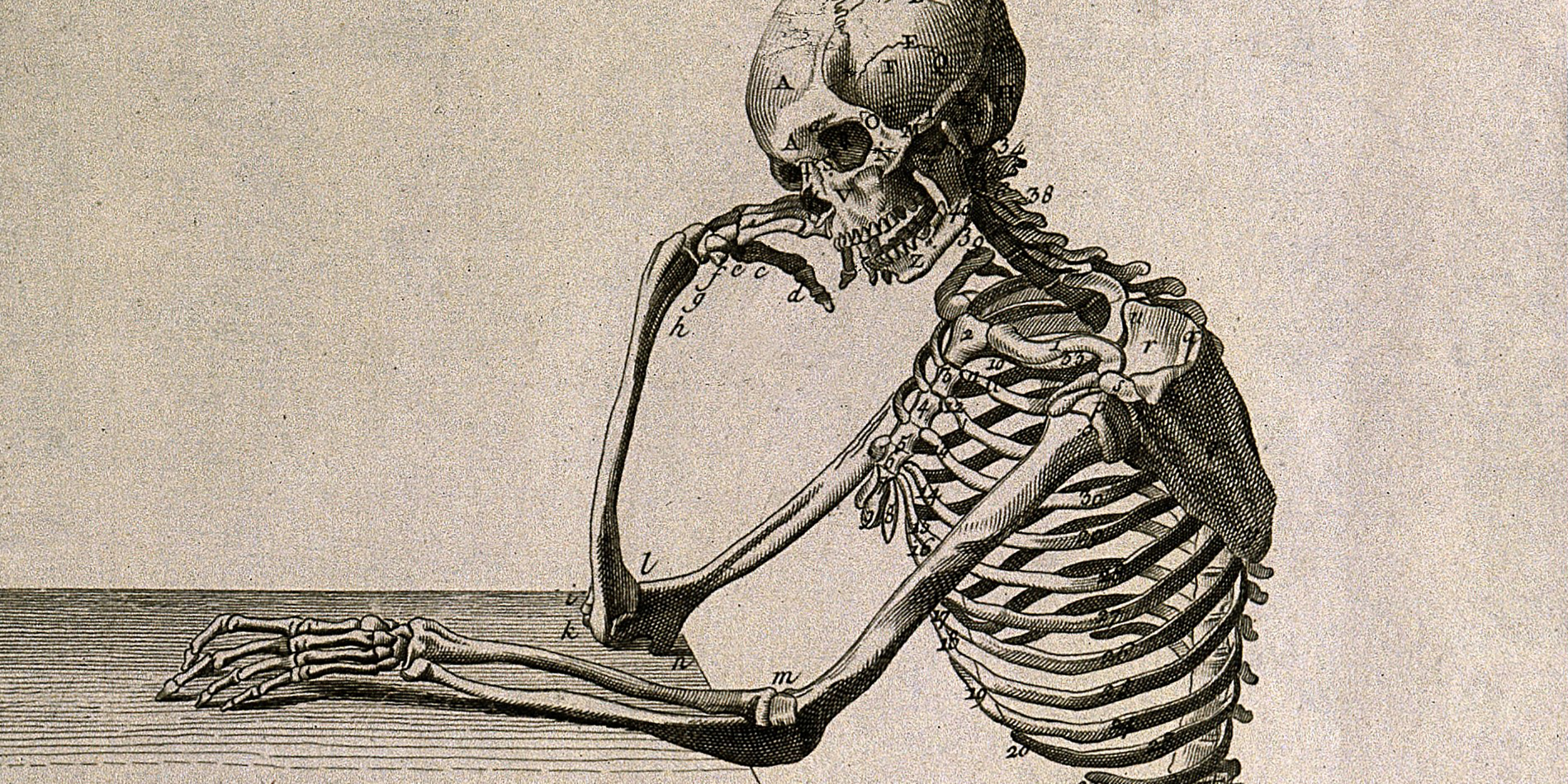

If you are squeamish, perhaps you should stop reading now, because what follows is not always pretty. Consider these chapter titles from Selzer’s book Mortal Lessons: Bone, Liver, The Knife, Skin, The Belly, The Corpse. Or these from Gonzalez-Crussi’s Notes of an Anatomist: On Embalming, Of The Dead as Living, Teratology (on monsters), Of Some Bodily Appendages. Other books by both authors treat equally unpleasant subjects.

Selzer is a New Haven surgeon. Gonzalez-Crussi is a Chicago pathologist. Both men are brilliant writers and scholars who probe for the human spirit among the flayed organs and spilled blood of the operating table and autopsy slab.

It is, in Selzer’s phrase, the “exact location of the soul” that they seek. For thousands of years theologians have sought to identify the organ of the body that is residence for our higher nature. Is it the heart? The brain? Or — as the ancients claimed — the liver?

Medicine is the offshoot of religion, and physicians still pursue the seat of our humanity. But they are no longer so naive as to believe that the soul sits curled up in a cavity of the heart or a lobe of the liver, like a butterfly in a chrysalis, awaiting revelation by the surgeon’s knife. No, the soul must be discerned in the totality of the body’s animated organs and their interaction with the environment, and it is revealed not by the parings of a scalpel but by the writer’s art.

Encounter with a devil

To illustrate the quest Selzer tells the story of an anthropologist, recently returned from the excavation of Mayan ruins in Guatemala, who appears at the infirmary with an abscess on his upper arm. The surgeon sets about enlarging the opening, to allow better egress of the pus. And then…

“What happen next is enough to lay Francis Drake avomit in his cabin,” writes Selzer. “No explorer ever stared in wilder surmise than I into that crater from which there now emerges a narrow gray head whose sole distinguishing feature is a pair of black pincers. The head sits atop a longish flexible neck, arching now this way, now that, testing the air. Alternately it folds back upon itself, then advances in new boldness. And all the while, with dreadful rhythmicity, the unspeakable pincers open and close.”

In this horrific encounter with a Mayan devil — the thumb-thick larva of a Central American botfly, emerging from the body of its unwilling host — Selzer the writer finds metaphors for ultimate evil, the vulnerability of the human frame, and the over-arching hubris of the surgeon. In the jaws of his hemostat he snares “the dark concentrate itself,” and in the tripartite ensemble of patient, botfly larva, and physician perceives something of the human soul.

The surgeon’s knife cuts living flesh. The performer of autopsies, on the other hand, sees only the body in death: Can such a morbid perspective — a rummaging within cadavers — illuminate life?

Pathologist Gonzalez-Crussi confronts the question head on. As a performer of autopsies he moves among diseased organs, trauma, the wreckage of senescence, and inviable deformations. “What in the name of heaven,” he asks rhetorically, “can be expected of one who spends his life surrounded by gloom and his working day among truculence, gore, and sadness?”

A revelation of sameness

It is a measure of Gonzalez-Crussi’s art as a writer that he withdraws from the gore of evisceration with a measure of the soul. Not least among the lessons he draws from the cadaver is an affirmation of the brotherhood of humanity, transcending race, gender, or other external differences. He writes: “Left to abstractions, our mind would fain seek refuge in philosophies that uphold our uniqueness, but the autopsy, in a most brutal way, reveals our sameness.” And the corpse teaches the pathologist-writer something about the vulnerability of life: “We should wish to take solace in thoughts that flatter our desire for permanence when the autopsy drags us, by the hair, into the spectacle of our own dissolution.”

Lest these grim lessons seem less inspiring than those offered by poets, let it be said that Gonzalez-Crussi’s essays are marked by a reverence for life and a sensitivity to human suffering that I have seldom found among practitioners of less morbid arts. If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, then the humane pathologist is no less capable than the poet of discerning the human soul.

“Poetic flights are all pardonable,” he writes, “but many are inaccurate.” He suggests (rightly, I think) that only scientific dissection of the human frame has the power to ultimately explain our emotional and relational life. But do not mistake this for a gross materialism, any more than is Selzer’s claim that flesh alone counts. If the human spirit can be fully exposed by dissection of the body, then there is no need for the surgeon or the pathologist to write.

So why does he write? Richard Selzer answers: “It is to search for some meaning in the ritual of surgery, which is at once murderous, painful, healing, and full of love.” And what does he find among the blood and gore? “That man is not ugly, but that he is Beauty itself.”

Which sounds a lot like Whitman.

I made a long comment about your cavalier treatment with unproved objections and condemnation of creation scientists but your system said something about repeating myself and it didn’t get through. It sounds as though you are one-way only and that you don’t listen to objections but that you just dismiss them. You’ll get nowhere doing that. Repent.